Tig Notaro on Finding Out She Has Cancer

"I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer."

There was no monumental day when I discovered the lump in my breast. There was only the day I was with Brooke and felt a lump on my left breast that I vaguely remembered feeling about two years earlier but had thought nothing of. I mean, did I feel one then? Perhaps.

And as I felt that lump I felt another one, on the right breast, which I also remembered feeling before and finding not as pronounced and even impossible to find on some days. Because of this, and because the lumps on each breast were nearly symmetrical, each on the outside, I believed everything was normal. I considered myself a healthy person. I decided that my lumpy breast tissue was merely the result of the ebb and flow of hormones. Brooke, however, believed I needed to get it checked out immediately. Instead of making a doctor’s appointment, I spent the next couple months teasing Brooke by removing my shirt and saying, “Hey, wanna touch my cancer?” It was really fun to walk past her holding my chest and blurting out, “Ow! My cancer!” And then, completely unrelated—as in, we did not connect this to my “benign” lumps—Brooke one day changed the words to the chorus of a popular Martina McBride chorus that seemed to be playing all the time on our local country music station. The song, “I’m Going to Love You Through It,” is about a man supporting his wife who has been diagnosed with breast cancer, and instead of singing, “Just take my hand, together we can do it, / I’m gonna love you through it,” Brooke sang: “Just take my hand, together we can do it / Your tits have cancer.” It cracked me up, it cracked her up. It was just ridiculousness. Neither of us stopped after “Ha ha your tits have cancer” to think, “Hmm . . . here are these lumps . . . I wonder if these particular tits do have cancer.”

Five months after I’d really noticed the lump on my left breast and almost two months after my C-diff and my mother’s death, I returned to L.A. having just recorded This American Life. My health was seemingly on the mend, but my relationship was now on its deathbed. Brooke had understandably become impatient with the hell that my life had become, and I had become impatient with her asking how I was doing since my answer was always “not good” or “getting worse.” By the time I’d begun snapping, “If I get any better, I’ll let you know!” I didn’t believe we were actually in love or had enough of a foundation to stabilize the relationship through these tough times. This vicious tension seemed to be a sign not only that our connection lacked depth but that we were trying to break up without verbalizing it. I soon reached the point at which I was even yelling at her to please leave me and go be with someone else. If she left me, I wouldn’t feel guilty—another negative emotion I didn’t have the capacity to handle at the time.

In order to get perspective on our muddled feelings, we decided to take a couple week-long breaks from our relationship, but I was unable to get the clarity I needed when Brooke continued to contact me. After the unsuccessful attempts at taking space from each other, we made an appointment with a therapist. While driving to my apartment, I asked her what she wanted to talk about in our therapy session, and she said, “Everything.” “Oh my God,” I thought, “I can’t do this.” I was certain that trying to mend our relationship would be yet another way I might find myself miserably dangling in purgatory. I desperately needed stability since so many things I’d assumed were concrete, or at least, here for the foreseeable future, had simply and quickly vanished. It became beyond apparent to me that we just needed to break up. Right then. By the time she dropped me off at my loft downtown, I was single and not quite ready to mingle.

Three months after Brooke had told me that I needed to get my breasts examined immediately, I went to the doctor’s for a follow-up checkup for C-diff and told the internist that I also had this lump on my left breast (the one on the right was so small and hard to locate I didn’t even mention it). I said it like “Hey, I also have this tooth that’s been kind of sensitive when I chew gum.”

She examined me, felt what I was talking about, and suggested that since I was 41, I might as well get my first mammogram. Three weeks after that, I went in for my mammogram feeling I was being quite thorough in my preventive care. When the doctor said she’d call with the results, I didn’t feel as though I was waiting to hear if I had cancer. I felt as if I was waiting to hear I didn’t have cancer. I forgot about the mammogram and went on with my life. Why wouldn’t I? No one that I knew of in my family had ever had breast cancer. I had quit smoking when I was 25 years old. Sure, I had started when I was eight, but I was still relatively healthy and young. And most of all, as insane as it may sound, I really thought because my breasts were so small, my likelihood of getting breast cancer was the same as a man’s: very slim, just like my teats.

I still had zero concern when my doctor’s office called to tell me I needed to come in to the cancer center for further diagnostic testing because my mammogram was abnormal. I’d heard from my doctor, and many other people, that abnormal mammograms that turn out to be benign are quite common. I brought Sascha, the ex-girlfriend who’d talked me onto the plane, because she wanted to be there for me when I got out of testing. She wandered into a nearby mall while I was poked and prodded. Put in gown after gown. Bed after bed. Machine after machine. What was supposed to be a quick 45-minute process turned into nearly five hours. I was told I could go get lunch, and met Sascha at a nearby deli. No part of me felt like I was waiting to hear anything other than: “Just as we suspected, it was an abnormal mammogram. How was that sandwich for ya?” I did not have cancer. There was no way the chorus of my life was going to be changed to: “Your tits have cancer / who knows who’s going to love you through it?”

At the end of my fourth hour at the cancer center, the doctor entered my room and asked, “How are you?” I said I was fine, but she was too cautious, and I was suddenly paranoid and wishing there was someone else in the room to help me gauge her tone. She gently told me that they’d seen the lump that I’d come in for on the left breast and that they’d also found one on the right. I couldn’t figure out if what I was hearing was scary. Was I being told I had cancer? If I completely freaked out like I wanted to, would I be overreacting? Would someone else hear all this and say, “Oh, Tig, you don’t have cancer. She’s a doctor and she has to say things like that.” I felt my brow furrow and heard myself ask if she was concerned. “Yes,” she said. “Actually, I am.”

“Wait, are you telling me there’s a chance I have cancer?” I asked, thinking that possibly they had the wrong information. Like maybe they had gotten my files mixed up with someone else’s. And besides that, my mother had just died, I had recently split with my girlfriend, and I had been in the hospital for C-diff. I was the single most unlikely person to have another bad straw piled onto the camel’s back. I’m not a superstitious person, but I was beginning to believe that I was on a bad streak and that life had made a decision to take me down.

Ira Glass soon set me straight on this point, reassuring me that everything happening to me only represented true randomness; that people think “random” means scattered when, in fact, randomness can look like a pattern. To prove his point, he told me that when the episode of This American Life that I appeared on was projected live into theaters around the world, and a raffle with two prizes for the entire viewing audience was offered, both winners were seated in the same small theater. And that, same as my back-to-back hardships, was truly random.

But lying down in the patient room at the cancer center that day, I didn’t feel like I was living in a random universe. I felt cursed. How quickly I had gone from always being annoyingly lucky in the eyes of my friends—having “Tig Luck”—to being pitied and feeling pathetic. I was no longer walking out of a comedy club and stepping on five one-hundred-dollar bills on the pavement beneath my car door. Gone were the days of deciding what I really wanted was an outdoor cat and coming home to find a ratty little thing with a sweet meow and bent tail curled up on an oil spot in my driveway.

The doctor said she couldn’t confirm anything without biopsies, but based on everything she’d seen today, it was quite probable that I did have cancer. She asked if I had any questions. I didn’t really react. I felt like I had just been told I had cancer but also like I had not been told that I had cancer. Here I was again: dangling in purgatory.

When I’d learned my mother had fallen and was not going to make it, I couldn’t fathom driving to the airport, taking my shoes off for security, boarding a plane, and then spending several hours strapped to a chair while hurtling through the sky. I wanted to be teleported. I had that same feeling right in this moment. My skeleton had been removed, and all hundred or so pounds that I’d become were collapsing under the gravity of reality. The tedium of traveling anywhere, even the short drive back to my apartment, seemed utterly impossible. Then I realized I didn’t just need to get myself home, I still had to get Sascha home, which meant merging with five o’clock traffic and heading in the exact opposite direction of my apartment, deep into the Valley.

We drove very silently and slowly toward the Valley. Sascha wanted to be with me, comfort me, and come home with me, but I declined. There wasn’t a single human being in my life who I wanted to be around. I didn’t want to be comforted by my most recent ex-girlfriends or my newest romantic interest. There was nothing I needed someone to say. I felt so alone, which only made me want to be alone. I didn’t want a hug. I wasn’t hungry. I was nothing. I couldn’t even cry.

When I finally pulled into my parking spot outside my apartment, I just sat there and exhaled, staring through the windshield. I imagined the aerial view of myself as a red target focused on the top of my car, as if there was a helicopter searching for lonely people with bad news. It would follow me as I walked into my apartment, and perhaps for the next several months. “What an odd job those pilots would have,” I thought, and then decided walking into my apartment and riding the elevator just shy of ten floors was something I needed to put off for a while.

The hour and a half I spent alone after dropping Sascha off and driving home had allowed me time to want to finally reach out to someone, so I called my manager, Hunter. Hunter only has four clients, and not to be braggadocious, but it’s a pretty safe assumption that I might be in his top three. I felt like a parent telling their kid that the person he depended upon was possibly not going to be around for much longer, that because I wasn’t sure I was going to be okay, he couldn’t be sure he was going to be okay. I know Hunter’s well-being wasn’t his concern in that moment, but it was mine. I’d been his client for over four years at that point, and we talked several times a day. He’s heard all about my romantic relationships, he’s visited me in the hospital, and he’s helped me move—all for just ten percent of my income. And now he was hearing that I probably had cancer. Hunter was silent for a few seconds and then his voice cracked as he asked me to keep him updated on what the doctors said. We spoke for a little longer and then got off the phone because neither one of us wanted to break down in front of the other. After hanging up, I sat in my car and finally cried.

The moment I walked into my apartment, there was a magnetic pull that forced me into my bed. I stared at my ceiling with only two thoughts: “There’s no way I have cancer” and “Oh my God, I have cancer and I’m going to die.”

When I’d left the doctor’s office, the doctor had tried to get me to schedule a biopsy, and I told her I had to record my podcast, Professor Blastoff, the following day and that I’d get back to her. I’m sure she hoped that when I got back to her I’d also let her know what exactly a podcast was. So, indeed, the day after my appointment, instead of going in for a biopsy or taking ten minutes to schedule one, I crawled out of bed and went to the studio to make sure ridiculous jibber jabber between comedian friends could be recorded and downloaded for free around the world.

People around me didn’t understand my unwillingness to move forward. They thought I needed to be proactive, and I thought they should have their mothers die and go through a breakup and be days away from a possible cancer diagnosis and see how quickly they drive to get their chest skewered repeatedly with what looked like a ten-inch pick so they can find out if they have yet another potentially deadly disease. I imagined they might also do what I did, which was stay under the blankets in their baggy underwear and imagine the worst.

On my fourth day home from the cancer center, I managed to stop examining my bedroom ceiling and submit myself to examining the doctors examining the tiny bloody chunks they were slowly pulling out of my tumors with their long, sharp tools and placing in a petri dish next to my face.

Ahhhhhh . . . heaven.

I left the biopsies feeling like I had been in a serious car crash, and I was supposed to appear on Conan the following night and then leave for a week-long run of shows at the Montreal Just for Laughs comedy festival. I had stubbornly not canceled these because I had wanted to believe that if I kept going through life like everything was normal, then it finally would be. I called Hunter and told him to cancel everything because I couldn’t move my body. Instead of an impressive tour schedule on my website, I was looking at: Canceled, Canceled, Canceled, Canceled, Canceled, Canceled.

On July 25, 2012, my fifth day home from the cancer center, I’d finally moved from my bed to my couch when the phone rang. I saw it was the doctor’s office and decided this was going to be the call that would put my mind at ease. I would be told that everything was fine, that my rack looked sweet. Instead, I was told that I had cancer in both breasts and that I needed to make an appointment as soon as possible with an oncologist and a surgeon to learn what stage I had and figure out a plan. I hung up the phone, thinking that I was going to die and my mother didn’t even know.

I put off meeting with the surgeon and oncologist for nine days. When I finally went, I brought my friend Beth. I’ve always known her to be nurturing, but not hyperemotional; calm and collected, but not stoic. I always listed Beth as my emergency contact, never imagining there would be an actual emergency. Yet here I was, standing next to my emergency contact, hoping she would comprehend everything and ask the right questions. Which she did, until the surgeon told us that I had stage II cancer in both breasts and that the tumor on the left was invasive. Invasive, as in, the cancer was not contained and might have spread, but they couldn’t know where it had spread or how much until they did surgery. I felt my mind float away. Beth didn’t ask questions and she didn’t move. She was frozen. We were both hearing information we were simultaneously trying to process and reject.

I don’t recall anything else the surgeon said, I only remember wanting to get out of my chair to go curl up in a ball somewhere on the floor of his office, like an animal trying to die. The next thing I remember was standing on the sidewalk and crying with my head pressed into Beth’s shoulder while she hugged me. This was truly an emergency contact if ever there was one. My crying, which I don’t even do much of privately, turned into sobbing and hyperventilating for all approaching and departing Beverly Center shoppers to see.

Needing my mother to comfort me about her death was an insatiable, unresolvable problem. And now, having cancer without having a mother brought on a similar, and similarly insurmountable, problem: I needed to go home, but I would forever be unable to.

Beth offered to drive me to my apartment, but I wanted to drive alone, saying to myself: “I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer.”

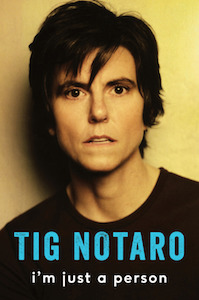

From I’m Just a Person. Used with permission of Ecco. Copyright 2016 by Tig Notaro. All rights reserved.

Tig Notaro

Tig Notaro is an American stand-up comic, writer, actor, and radio contributor. In 2015, her HBO stand-up special premiered along with Tig, the Netflix Original Documentary about her life, and she returned fro season two of the critically acclaimed series Transparent on Amazon. Tig remains a favorite on Conan and This American Life, tours internationally, and enjoys bird-watching with her partner at their home in Los Angeles.