Through the Lens of Love: Nicholas Boggs on His New Biography of James Baldwin

Danté Stewart in Conversation With the Author of “James Baldwin: A Love Story”

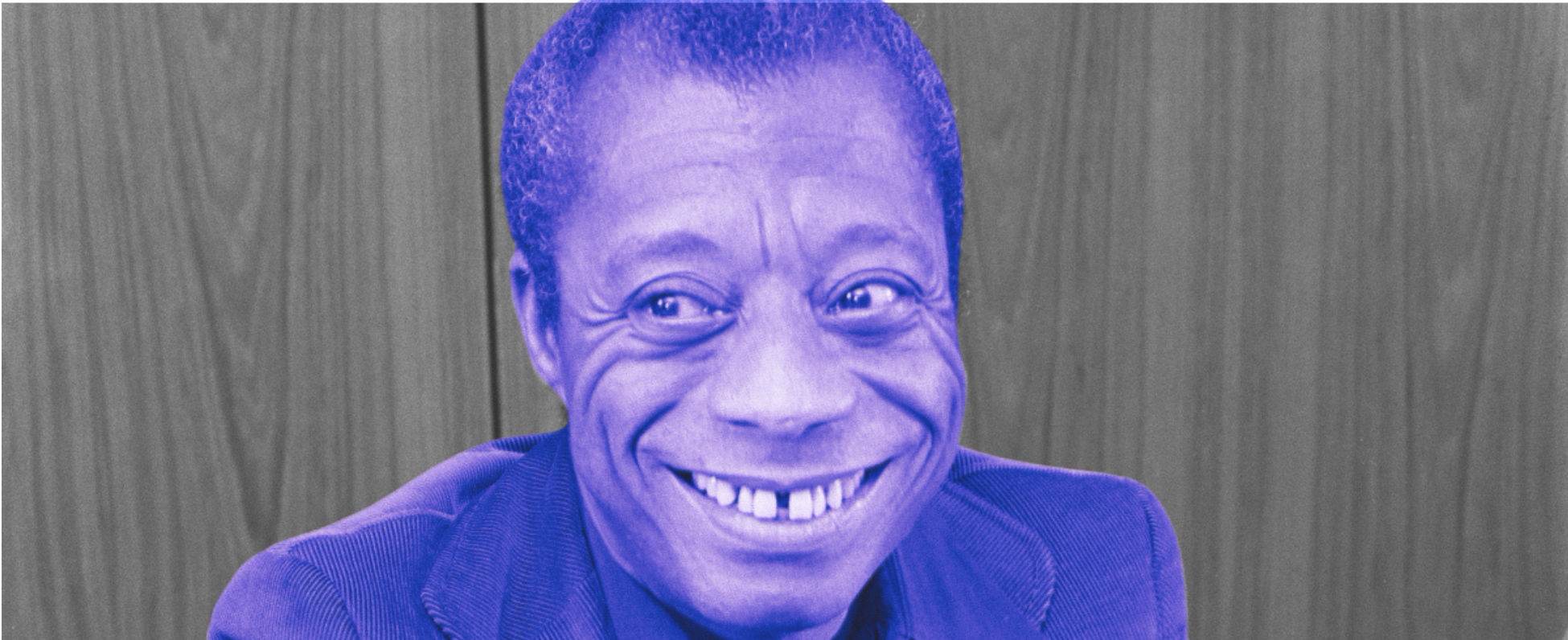

Reverend Danté Stewart is an author, award-winning writer, and cultural critic, keenly attuned to issues of faith, justice, and stories of the heart. Nicholas Boggs debut biography, Baldwin: A Love Story, frames the life of legendary author and activist, James Baldwin, through his romantic and platonic relationships. Stewart poses questions to Nicholas Boggs about his undertaking a chronicle of the life of an iconic artist: how Boggs encountered his subject, the “romantic dimension” of Baldwin’s life, his perspective on “ugliness,” and on exile.

*

Danté Stewart: What brought you to Baldwin? Particularly the angle of Baldwin through his loves — either familial, platonic, or romantic? Why Baldwin, why now?

Nicholas Boggs: I first read Baldwin in my public junior high school in Washington, DC, after seeing his image on the wall of my English teacher’s classroom. That, I remember, but this teacher recently reminded me that I wore a suit to class one day and did a presentation on his life, which I don’t remember at all! But clearly the interest in Baldwin began early. The love part came out of my research into Baldwin’s out of print children’s book, Little Man, Little Man, which I discovered when I was an undergraduate, at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The book’s illustrator, Yoran Cazac, was a little known figure from Baldwin’s life, and presumed dead. But I was able to track him down, very much alive, in Paris in 2003. Turns out he was Baldwin’s last great love, and that was a springboard into my interest in the other beloved figures who loved, inspired, and sustained Baldwin—his mentor, the painter Beauford Delaney; his great love Lucien Happersberger, to whom he dedicated Giovanni’s Room; and the Turkish actor Engin Cezzar. Baldwin lived this incredible life, and while there have been some great biographies published in the past, it’s been decades since and new archives have become available. We need his perspective through the lens of love right now, because hate, obviously, is everywhere.

We need his perspective through the lens of love right now, because hate, obviously, is everywhere.

DS: You titled the book James Baldwin: A Love Story. I love that the title suggests that there is a romantic dimension to his life. Not to say that his life should be romanticized in any way, but there is a quality of beauty that can be experienced once we step back and look again at Baldwin, now some thirty years since the last major biography. In your research and writing of the book, what did you learn about how Baldwin thought of love toward himself, toward others, and the larger human world?

NB: I think Baldwin understood the significance of love, in part because his own self-love was so hard-won. He grew up being told he was ugly, a sissy. Love was, as he put it, “a battle,” a “growing up.” And he drew upon his own struggles to explore how Americans in general and white Americans in particular refused to grow up, refused to let go of their false innocence, refused to come to terms with the past (and the present) which amounted not just to the continued oppression of others but to a kind of spiritual self-strangulation. The epigraph to my book comes from a postcard Baldwin wrote to a friend, and I think it really encapsulates his vision—philosophically, politically, and personally (and for him they couldn’t really be separated): “Love is the only reality, the only terror, and the only hope.”

DS: In the book, you chronicle the ways Baldwin’s relationship and understanding of love evolved, deepened, and in some ways severed. It is a kind of journey of illumination and grief, human beings doing the best they can to live together and separate. Of the four — Beauford, Lucien, Engin, and Yoran — which did you find the most surprising and compelling?

NB: I can’t possibly rank Baldwin’s relationships with these men, as they were all essential, really, to the man and writer he became. But in terms of what made them the most compelling as a whole was how connected all four “love stories” were. Beauford was Baldwin’s “spiritual father,” especially early on, and later he introduced him to Yoran Cazac in Paris in the late 50s. Yoran shared many qualities with Lucien Happersberger, and Baldwin became the godfather to each of their sons. Lucien was the inspiration for Giovanni’s Room, and then Engin Cezzar played the role of Giovanni in the Actor’s Studio workshop production. The structure for the book emerged very organically, albeit over the course of many years, because of precisely these through-lines and correlations, and in all cases Baldwin would separate and come back together with all of these men, as you say, in fascinating but ultimately life-saving ways.

DS: Baldwin seemed to be haunted by the idea of “ugliness” and, in some regard, being of little to no use. This seems to me to also be juxtaposed by his unshakable belief within (this had to be the case because in spite of everything, he kept on believing) that he was to realize the “dream” he had within him from an early age. What, to you, did you find about Baldwin that drove him? How did his relationships shape how he understood himself and his own journey?

NB: This is such a great question, and there will always be something ineffable, I think, about what makes a great writer or artist capable of the kind of perseverance that Baldwin had. (As he once famously suggested, probably not giving himself quite enough credit in the process: “Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but, most of all, endurance.”). What drove Baldwin, I think, was an unshakable curiosity about other people and about the human condition. It’s why he could sit down with clearly racist people and try to learn from them, to learn what made them tick. He really got inside their heads. (Think about his short story, “Going to Meet the Man,” written from the perspective of a bigoted white sheriff, for example). He was also, of course, driven by love. Love for his family. He wanted to succeed so he could help them and his mother in particular and make them proud; hence, his recurring dream of becoming a famous writer so he could drive them around in a fancy car and go to fancy restaurants. But he was also driven by something deeper, by a moral vision, and commitment to justice. I also think he knew he had a gift and a responsibility that drove him to be a “witness” as he put it. Fortunately, he had people around him who recognized this early on—yes, his mother, but also many teachers, and editors. For all of his setbacks, as Sarah Schulman recently put it, the world wanted him to be a writer.

What drove Baldwin, I think, was an unshakable curiosity about other people and about the human condition. It’s why he could sit down with clearly racist people and try to learn from them, to learn what made them tick.

DS: As a queer black writer, Baldwin, as you write, seemed to always challenge and wrestle with this notion of sex and sexuality — especially the ways in which religion has done almost irreparable damage on what we think it is to be human and live together. As you begin to deepen your exploration of Baldwin’s relationship to each of those words and experiences, which lies at the heart of your book, what possibilities does Baldwin’s life hold out for us today? How did he find his way in the world, in his queerness, without shame, with struggle and wrestling, and yet with a kind of freedom that allowed him to be who he was in spite of everything he felt within and saw outside of himself?

NB: In many ways it was Beauford Delaney who helped him with all of this. Baldwin wrote that Delaney was the first person who made it seem possible to be a black man and an artist, but he also gave him a model for being a different kind of black man, period—one connected to his interiority, one who risked vulnerability. In many ways Beauford struggled with his sexuality even more than Baldwin did, but he still showed him a pathway. Then it was getting away from America, with all its projections and phobias and bigotries connected to race and sexuality, by going to France and then falling in love with Lucien, that allowed him to find his way, as a writer but also in personal terms. But I would say, it really was his writing that ultimately allowed him to free himself, especially when it came to his sexuality. In Go Tell It on the Mountain, he wrestled with his past, his desires, somewhat subtextually. Then in Giovanni’s Room he put more on the table, even if he told it through a basically white love story. Late in his life, in the novel Just Above My Head, he finally told a black queer love story (though there had been some of that in Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone). And in his late essays like “To Crush a Serpent” and “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood,” and his introduction to “The Price of the Ticket,” he became fully liberated, I would say, in looking back at his early life with clarity and truth. In terms of the possibilities that his work holds for us today, there’s so much more to say about them, many conversations for us all to have, and of course the important Eddie Glaude Baldwin book, Begin Again, is very helpful, as is your own terrific writing on Baldwin, Dante!

DS: In the book, you write of Baldwin’s not technically being considered an “expatriate” but as he would call it, a transatlantic “commuter.” He felt a sense of exile from his native land. He also felt a disconnection from the places he traveled to even as he felt a deep sense of connection with the people and the landscape. It seems to me that in his very existence, Baldwin embodied the black American’s relationship to home, as a place, a world, an experience, and a metaphor. In your research and writing, what was revealed to you about how Baldwin can help us think about home now, in a country which has become for us, as it once did for him, marked by increasing disillusionment?

NB: Baldwin used going elsewhere as a form of experience that gave him perspective and in many cases the relief and respite he needed to examine the country of his origin. So he traveled to Paris, Istanbul, Switzerland—places where he felt like or should have felt like a stranger. The United States was still his home and a place of connection but also a place of profound alienation, especially as a Black American and a queer man (although that wasn’t his language of choice). I am always a bit wary of suggesting how Baldwin can help us today, in part because I would never want to speak for him, and in part because he was an idiosyncratic thinker and often changed his positions. In fact, I would say that his willingness to change his mind is one thing we can learn from him. To mention just two examples: after his first visit to Israel in the early 60s, he came to a different view on the plight of Palestinians after witnessing their horrific situation and how they were being treated. He also became much more progressive around gender—in his writing and in his life. He listened to Nikki Giovanni, to Audre Lorde (even if he said some unfortunate things along the way,) and he really listened to Toni Morrison, who helped him find and hone the voice for the female narrator of If Beale Street Could Talk. Lastly, he looked to others, to the communities he created in Istanbul and the south of France, to keep him alive, to make his writing possible, and all of it rooted in love.

DS: For Baldwin, the work was never finished. What I mean is that the work of living, being alive, living in the real world, being around real people in real places, doing the best you can to be a “light” — as he writes in “Nothing Personal”. As you have finished this magisterial work, what is left undone of the work that Baldwin desired for himself and for us?

NB: In our current moment, which is so dark and dismaying, it can feel like almost everything is left undone in the work of liberation that Baldwin tried to dream and write into being. But I try to tell myself that this is a feeling, not a fact, and that we don’t have the luxury to treat it as terminal. Baldwin didn’t. He kept believing in the power of individuals and of collectives, of truth-telling, and a tough yet real and vulnerable love. I think his life, and hopefully this book, provides something of a roadmap for survival and hope, despite it all.

_______________________

Nicholas Boggs’ James Baldwin: A Love Story is available now from FSG.