Three Trees That Tell the Story of

Ancient Cultures

Legends of the Kapok, Totara, and Judas Tree

The following is from The Story of Trees by Kevin Hobbs and David West.

*

The ceiba or kapok is one of the tree wonders of the world. The Aztec, Maya and other pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures considered it sacred—a symbol of the link between heaven, earth and the world that was believed to exist below. This was a giant tree upholding the world, with roots reaching down into the underworld. According to the folklore of Trinidad and Tobago, deep in a forest there exists a huge kapok tree known as the Castle of the Devil. In it lives Bazil, the Demon of Death, imprisoned by a humble carpenter who had carved seven rooms out of the tree, and tricked Bazil into entering it.

The kapok tree is native to Mexico, Central America, the north of South America, the Caribbean and tropical west Africa. It is one of the largest flowering trees in the world, often exceeding 50 meters (165 feet) in height. An extended buttress of flattened roots, reaching 10 meters (33 feet) or more up the main trunk and as much as 20 meters (65 feet) across the ground, supports this wondrous colossus, enabling it to grow in shallow soil. One of the most remarkable features of the tree is the conical thorns that protrude from the young branches and trunks. These distinctive protuberances are a regular feature of Mayan art, portrayed on pottery incense burners and cache vessels. Many funerary urns have effigies of ceiba thorns on their sides.

However, it is for the cotton-like fluff obtained from its seed pods that the kapok tree is best known. The material is inside the long, green, tamarillo-shaped fruit that surround the seeds to aid their dispersal by the wind. Kapok is waterproof and much lighter than cotton; it is most often used as a stuffing material, although it has now been largely superseded by synthetic fibres. It is now mostly grown commercially in the rainforests of South East Asia, particularly in Java, hence Java cotton, another of kapok’s names.

The kapok is the national emblem of Guatemala, Puerto Rico and Equatorial Guinea, and appears on the coat of arms and flag of Equatorial Guinea. In Sierra Leone it is a symbol of freedom for the slaves that fled there.

*

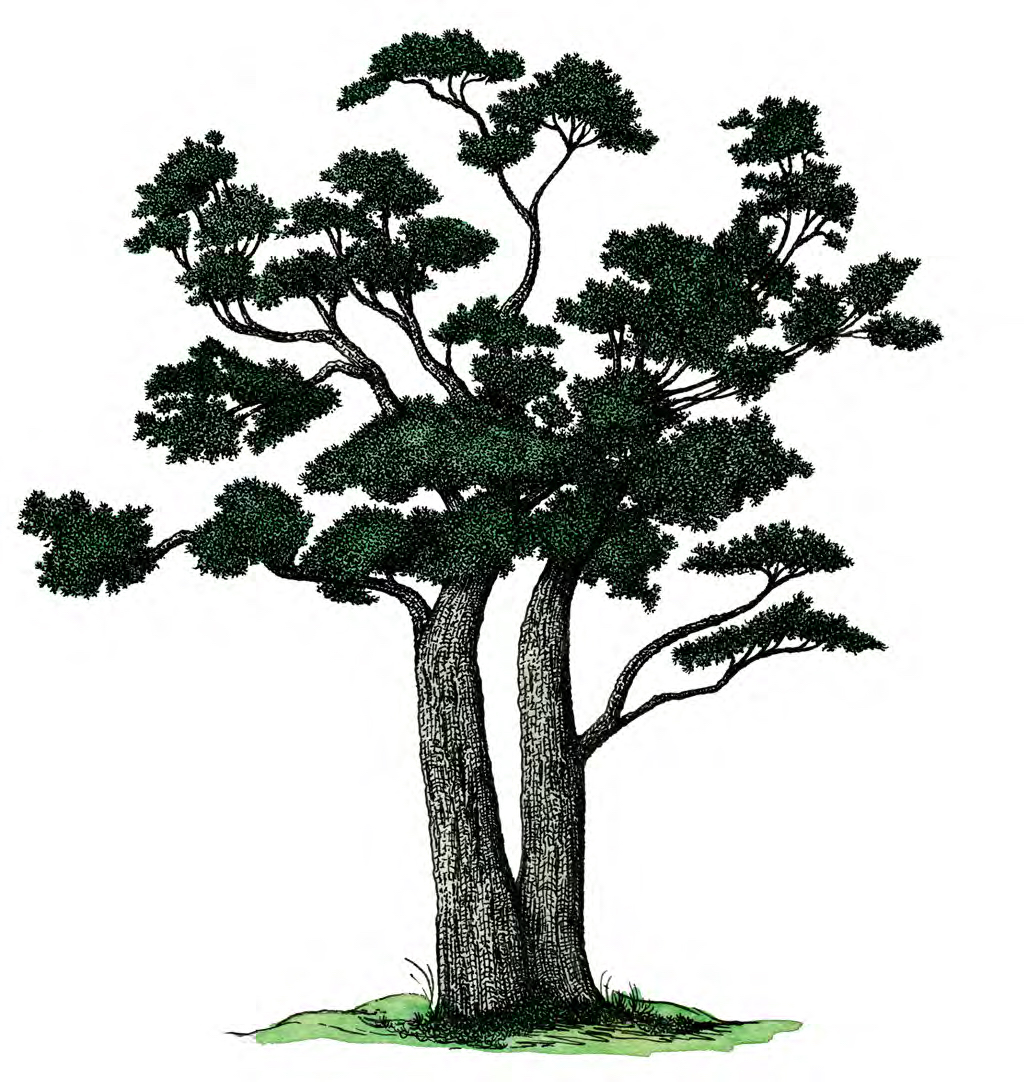

The tōtara is a canopy-topped conifer of the rainforests of both New Zealand’s North and South Islands, although it is more common to the north. It is a majestic and ancient giant of prehistoric times. For more than 65 million years its scaly, needle-like foliage has evolved into flattened, broad, greenish-brown leaves that are stiff and prickly to touch. This adaptation has been the key to the tōtara’s success, allowing it to compete with the more highly evolved flowering plants that eventually dominated the landscape.

The Māoris, who first arrived in New Zealand from distant South Sea islands 800 years ago, prize the tōtara above all other native trees, chiefly for its timber, which is durable, resistant to rot and straight-grained, making it ideal for the making of spoons and other implements. It is a hardy species that will grow in almost any soil, and is the perfect building material for the Māori waka or canoe, which ranges from a few meters long, for fishing purposes, to the waka taua, a war canoe big enough to carry 100 warriors. Amazingly, whatever the size, most wakas are built from a single hollowed-out tōtara tree. Another use of the tree is whakairo, traditional carving which includes icons that are said to take on the character of those they represent. A fine early example of this art depicts Te Uenuku, the god of rainbows, carved between ad 1200 and 1500.

The tōtara’s resistance to rot stems from its heartwood, which contains a chemical known as totarol. Its antimicrobial properties have been used by the Māori to treat fever, asthma and coughs. Although it is currently limited to use in cosmetics, its properties are subject to the attention of modern scientific research. Unfortunately, the arrival of European settlers, known by the Māori as Pākehā, resulted in most tōtara trees being felled for building or fence posts to enclose vast tracts of land for farming. The tree is now protected, and the use of its wood limited to that of dead trees. And at least one tōtara is believed to be more than 1,800 years old. This is Pouakani, the oldest living tōtara. It has an impressively stout trunk, deeply fissured with the complex surface roots that grow to ensure the tree’s stability during volcanic eruptions.

*

The Judas Tree: There is little or no evidence that Judas hanged himself on a tree that now bears his name, or indeed any other tree if the Acts of the Apostles is to be believed. According to this book of the Bible, an unnamed man betrayed Jesus, bought a field with the 30 pieces of silver reward, and, “falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out.”

But the legend and the tree at the center of it remain. The Judas tree has a liking for a dry climate and is native to Spain, southern France, Italy, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. It is a small tree with a narrow trunk topped by a spreading crown. It is covered in early spring with a profusion of magenta-pink flowers, which appear before the leaves. This gem of a tree has been in cultivation in the British Isles for more than 300 years. Some of the oldest and best specimens are to be found in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Like most of its kin in the legume family, it produces its seed in pods. These are often brightly colored, last well into the autumn and then persist on the leafless branches throughout the winter. The flowers of Cercis siliquastrum are edible, and can be eaten in mixed salads. They figure frequently in 16th- and 17th-century herbals, but are rarely used in this capacity today.

The name “Judas tree” may derive from the French arbre de Judée, “tree of Judea,” a reference to the region in which the tree was once thought to grow wild. There is a strong myth that Judas Iscariot hanged himself from a tree of this species in the Hakeldama (the Field of Blood), in the Valley of Hinnom surrounding the old city of Jerusalem. Another origin of the name comes from the flowers appearing on bare branches, often directly on the trunk, making the tree apparently ooze blood—also symbolic of Judas’ possible suicide.

There are many notable selections of this species. The unusual white-flowered form is especially beautiful, and gained an Award of Merit from the Royal Horticultural Society when it was exhibited in 1972. The variety “Bodnant,” named after the garden in North Wales where it was first observed, is particularly fine, with deep reddish-purple flowers and maroon seed pods.

___________________________________________

Excerpted from The Story of Trees by Kevin Hobbs and David West. Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Hobbs and David West. Excerpted by permission of Laurence King Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Kevin Hobbs and David West

Kevin Hobbs is a professional grower and plantsman with over 30 years’ experience in the horticulture industry. He is Head of Research and Development at world-renowned Hillier Nurseries in Hampshire, UK. David West runs his own nursery business, specializing in the commercial production of rare trees, and he runs a mail order nursery, PlantsToPlant.com. They are the authors of The Story of Trees: And How They Changed the Way We Live.