Those Who Wander: A History of Nomadic Pastoralism in Southeastern Europe

Kapka Kassabova Explores What’s Left of an Ancient Tradition Marked by a Century of Upheaval

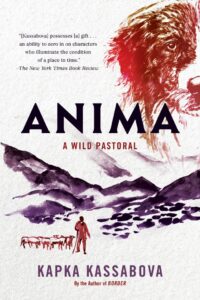

This story begins with a picture. A man stands inside a circle of goats. Their black-and-white coats touch the ground. They have horns like sabers and hermit faces. He does not look at the camera but at the goats. Consumed, I thought, he is consumed by his animals. Immediately, I knew that a way of life that stretched back to some unknown time was contained in this moment. The picture began to move before my eyes. I saw a fanning out of human and animal flocks across mountains and river flats, like black-and-white rugs being aired in the wind. And I felt an urge to follow them.

Outside the frame was the whole of the Pirin Mountains. I’d spent several seasons along the Mesta River that defines eastern Pirin. That became Elixir. It was an old mountaineer from Mesta who gave me the album with this moving picture and by doing this, he opened a new gateway—through the center of the mountains to their western side. That side was unknown to me. At home in Scotland, I’d open the album of Pirin and turn the pages of its seasons: granite peaks, millennial pines, edelweiss like cosmic velvet, golden eagles, lone people in remote villages and—the man with the long-coated goats.

The reason why these dogs were disappearing was because the pastoral ways were disappearing.

This is what I found out: his name was Kámen, and he and his brother Achilles were experts in a legendary breed of dog called Karakachan. The Kará-kachán is an ancient dog, one of the few remaining ones. I’d come across them in earlier visits with mountain shepherds. Their eyes were human. They walked with the loose gait of wolves and the puppies were like bear cubs, with expressions so knowing they stopped you in your tracks and made you stare as if into the eyes of an old friend. They were aloof and conscious of it: we don’t need you, you need us and here we are because love is different from need. Superior, in fact.

These dogs had followed the pastoral trail across mountains and centuries. No—they had made it. Dogs, humans, horses and grazing animals, together. Any paths that are there on the map, or off the map are there thanks to these dogs.

Just thirty years ago, Karakachan dogs were in danger of disappearing. To think that these dogs that were more than dogs and at the same time the epitome of dog, would be extinct by now, had it not been for these two brothers was unthinkable. The reason why these dogs were disappearing was because the pastoral ways were disappearing. They still are, thirty years on.

Moving pastoralism emerged in Central Asia, the Balkans and the Mediterranean several thousand years ago. It began with the domestication of sheep and goats, and it was in its European heartland that nomadic shepherding lasted the longest—until the middle of the twentieth century. Even the word nomad hints that wandering and grazing go together: the Greek nomas means “wandering shepherd” or “wandering in search of pasture.”

There were four cataclysms in the last 100 years that led to the extinguishment of the nomad hearth. These convulsions affected first the nomads and eventually, everyone in the pastoral world. With them came the end or near-end of breeds of animals, humans and ways of being

The first was the drawing of new national borders between Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey in the wake of the First World War. This made the movement of caravans exorbitant and dangerous.

The second was the complete closure of these same borders after the Second World War when the Cold War froze relations and the Iron Curtain put an end to all movement of animals, people and people with animals from the Aegean and Thracian lowlands of the Balkans to their mountainous interior. The old transhumance trail was severed but nomads endured in each country for a bit longer. The last nomads were the Karakachans.

The third cataclysm came in 1957: collectivization. It meant the wholesale theft and sometimes the slaughter of animals belonging to transhumant shepherds and to all livestock owners in Bulgaria. That was almost everyone outside the cities, and the cities were still small in an economy driven by the very thing that the communist state most coveted—large-scale sheep breeding and agriculture. The Karakachans had more animals than most. It’s all they had and they lost it.

The fourth cataclysm came forty years later: privatization. Communism collapsed and the state cooperatives politically engineered at the cost of so much human and animal suffering were expediently dismantled. In a free-for-all, animals were slaughtered en masse or sold and shipped abroad, and vast infrastructures were left to decay. With that came the quick decline of the guardian dog.

In the late 1990s, a group of penniless animal lovers took out a loan and moved into the crumbling village of Orelek in western Pirin. The mission was to establish a haven for endangered breeds of dogs, sheep and horses. Over the centuries, those breeds were preserved by the Karakachans with religious devotion. It all comes back to them.

The Balkan Karakachans are one of the oldest nomadic peoples to have entered modernity with their animals. They are Greek speakers of mysterious origin, probably descended from pre-historic Thracian-Illyrian pastoralists Romanized and Hellenized over time. It is impossible to know the homeland of the Karakachans. They came from several different places but in recent centuries it has been, symbolically at least, the Pindus Mountain. Though most of them never set foot there because they were scattered over so many other mountains across the southern Balkans. It’s the nature of the nomad.

Nobody knows for sure why the Karakachans are called this, but kara-kachan means “black fugitive” in Turkish. True, they wore clothes spun from the wool of their black sheep, but it was the way they were seen by others too: quick-moving wanderers who could cross any terrain with their ancient-looking animals often at night, without leaving a trace. The Greek is Sarakatsani, which is simply a Hellenized form of Karakachani, but some fancy that it might derive from their mooted homeland of Sirako in the Pindus and Sirako means “sad” in Albanian, “poor” in Romanian and “orphan” in Bulgarian—yet another tale of how nomads were perceived by the settled ones. But the settled ones were not always settled.

Pastoralists have criss-crossed the Balkans for thousands of years and with time, the difference between nomads and settled pastoralists became more marked. Although everyone with grazing animals walked an established trail, there was a difference in scale and social set-up. The nomads travelled as communities and covered hundreds of kilometers between winter and summer pastures and lived in seasonal huts. Settled pastoralists, like the highlanders of Pirin, also covered large distances between lowland and highland pasture, but only the men went off with the animals, while their families remained to keep the village fires burning.

The Karakachans… were indeed the exception to the rule; the rule being settled living.

The Karakachans lived the nomadic life to the end. Nobody knows when the beginning was. Their language is a northern Greek dialect with words that go back to the time of Homer and with Balkan words woven in—Albanian, Bulgarian, Turkish. They were Greek Orthodox practicing a blend of stiff Abrahamic patriarchy and worship of the Virgin Mary and Saint George, protector of shepherds. Their own identifier was Vlachi. That’s an umbrella term for moving mountain shepherds. There was another big group under that umbrella, the Aromanian Vlachs, but the two groups kept themselves apart and spoke, dressed and treated animals differently. The Karakachans saw themselves as exceptional. And, like all the nomads, they were indeed the exception to the rule; the rule being settled living.

There’s a vocabulary that goes with nomadism. For centuries, all Balkan nomads were called one of two things: Vlachi or the more disparaging chergari—rug people, ones whose homes are made of rugs. Rugs carried by horses, then horse carts, then trains and finally, not at all. The chergari included the Gypsies and in some sense, all nomads were seen as Gypsies. Gypsy is synonymous with the eternal traveler.

The earliest written evidence of Vlachs is from an early eleventh-century Byzantine writer. He talks to a group of Vlach men in Thessaly who are about to join an armed revolt against the imperial authorities (a recurring theme for shepherds, that). He asks them: “and where are your women and children?” “In the highlands of Bulgaria,” they answer, “with our flocks.” In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries there came another lot of shepherd nomads—the Yuruks, Turkic wanderers sent by the Ottoman state as settlers. Unsettled settlers, that is. The word Yuruk means “walker” or “one who got away.” Inconveniently mobile in their Anatolian homeland, they were more useful to the empire in the Balkans. They stayed for a few centuries and made their mark but the others were here before them and stayed after them, until they too were dispersed and settled.

Only their animals remained in the hills—just.

The mountain sheep was the first grazing animal to be domesticated by humans. It happened around 11,000 years ago in Central Asia and south-east Europe. The Vlachs called their mountain sheep “the oldest sheep in the world” and studies show that they were probably right. It is the same with their mountain horses, donkeys and guard dogs who all evolved but remained genetically stable over time thanks to the—oddly enough—conservative nature of nomadic life. These breeds of animals have all come to be known by a single word: Karakachan.

And miraculously, some of them were still around. I found Kámen’s email and asked if I could visit.

“If you must,” he replied.

__________________________________

Excerpt from Anima: A Wild Pastoral by Kapka Kassabova. Copyright © 2024 by Kapka Kassabova. Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press.

Kapka Kassabova

Kapka Kassabova is a writer of narrative nonfiction, poetry, and fiction. She grew up in Sofia, Bulgaria, and lives in the Scottish Highlands. She is the author of Elixir, To the Lake, and Border, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.