Thomas C. Foster on the Seven Deadly Sins of Writing

"You cannot let worry win."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

If you hang around the writing racket long enough, you will see every sort of writing success and failure imaginable—and some you can’t imagine. I spent forty years teaching courses in writing and in literature where writing was a major component. Both during and after that time, I have been writing more or less steadily, sometimes frantically, once in a while ecstatically.

Through all that time, I have seen—and accomplished—all manner of failure. For some reason, students would sometimes come to my office to apologize for their poor (in their estimation) efforts, as if they had let me down personally. Often it turned out that the writing was anything but a failure, but it didn’t strike the student as a winner. Lacking any means of absolving themselves, they were asking me to do so for them. After offering what help I could, I obliged. In one terrible case, a brilliant mature student, although far too young for this fate, closed my door (something I never did on my own) and told me that trying to read and write for my course had revealed a change in her brain, an early-onset, not-yet-specified dementia. We wept together. Usually, such talks were much more mundane, with students seeking help after tying themselves up in knots. Help was one thing I had plenty of, both on my own and in sending them to our excellent writing center where their peers had knowledge and skills under less threatening rubrics than “professor.”

But here’s the thing about those visits: they rarely involved technical issues of committing prose to paper. Their knots were more existential than procedural. Mostly, they had thought themselves into corners and couldn’t turn around and walk out. When we would get down to the specific issues they were having, they came down to one or two of the same handful of stumbling blocks I heard confessed again and again. Although never quite sure of the number, I came to think of them as the Seven Deadly Sins of writing. You may find them dispiritingly familiar. But take heart—they could have been the Dirty Dozen.

Worry

Self-doubt

Overconfidence

Muddiness

Vagueness

Poor structure

Dishonesty

Notice that nowhere on this list is there a mention of semicolons. Or subject-verb agreement. Or sentence fragments. All of those things can be fixed. What kills writing is more basic than those surface-level errors, even if those tend to be the first thing people notice. But they only exist once the piece of writing does.

The Deadly Seven prevent writing from occurring in the first place. Or, like overconfidence and dishonesty, they create something that is rotten at its heart, and no amount of surface grace can improve that sort of decadence.

Not every first attempt at structure works out.

Self-doubt is the companion that never leaves, that tries to insinuate its way into every moment of the writing process. Think of it as the infestation of termites trying to chew down your house of words. It is also, however—and this is why it is so insidious— related to a necessary caution that writers need: Is this the right word? Am I conveying what I intend to? Is there a better paragraph arrangement here? And so on. As with anything taken to extremes, caution can become disabling. The mind is a delicate instrument and responds badly to excesses of any kind.

Overconfidence often follows self-doubt as the writer begins to feel more in control of the process, more assured about their abilities. The result can be a pendulum swing to excessive, unwarranted assuredness. Then, when doubt begins to sink in, they crumble. Either that or their overconfidence leads the writer to attempt too much, in too small a space with too few tools. My most notorious failure: the inability to write a book on contemporary Irish poetry that I knew I could write. That disaster led to my titles that begin, “How to Read” and end, “Like a Professor.” I assumed that I had an idea structure that, in the end, never materialized. The solution to both self-doubt and overconfidence, two sides of the same counterfeit quarter, is a dispassionate inventory of the writer’s skills and acumen. If we can identify the strength of the base from which we write, we can avoid underor overestimating our ability to do the job.

Muddiness results from lack of clear thinking, which can take a thousand forms: poor logic, unclear explanations, ambiguous motives, failures to wrestle the material into shape. As with numerous other sins here, no amount of surface repair can correct a structural problem. The corrective action is a simple, unpleasant question: Do I understand what I am saying well enough to convey it to my readers? Too often, the answer is negative. The tricky part of muddiness is that, if our thinking is muddled, we may not see clearly enough to fix it. Most times, however, dismantling the writing back down to the level of naked ideas—that is, unadorned by rhetoric that can obscure weaknesses—will reveal where the writer has gone awry. You can also address muddiness by purely formal strategies. For instance, rewrite the paper or whatever it is as a series of short, simple, declarative sentences, minus transitions. Stated so baldly, there is no place for mud to hide. You will find it and can address it. Then you can build it up into something that sounds as if written by a grown-up and not a fourth grader. First, though, back to fourth grade, which wasn’t so bad after all.

Vagueness can take a number of forms, but they often stem from preferring generalities to specifics, which results in the lack of detail. That term may suggest insufficient use of evidence, and that is one manifestation, but there can be others. We may fail to spell out our logic step-by-step, the way we wanted in geometry class to skip from step one of a proof to step twelve because it all seemed self-evident to us. Maybe that wasn’t you, but it was most certainly me. Or vagueness can manifest as a shortage of content words. The solution is usually to burrow into the text, into the meat-and-potatoes of the subject, into the specifics of the issue, pushing closer when our first impulse was to work at a distance.

Poor structure dooms many writing projects from the beginning. The writer has not found the mechanism for ordering the ideas. This issue presents more commonly in analytical or argumentative writing than in narratives. Absent or faulty structure undermines the writer’s aspirations for the piece.

I once or twice read for a “writing contest” in the local schools. I put that term in quotation marks because, while winners really were announced, some teachers compelled their students to enter, which obviates the notion of a contest somewhat. Besides, every entrant got an award (where writing is involved, I think participation patches, those sources of irritation for persons of a certain age, are perfect). If they wrote, if they expressed themselves, and especially if they enjoyed doing so, good on ’em, I say. One memorable year, I read entries by third graders, among whom, alas, structural thinking is not a common virtue. This did not slow them down one bit, but it hindered their poor reader a good deal. That was okay, though, and no fault of the students who, at that age, in many cases have not reached the developmental stage where they can inevitably sequence and structure ideas or experience. Some have, and all will sooner or later, but not right then.

You are not in third grade, having long since passed that developmental stage that I needed my grade-three writers to have reached. Even so, not every first attempt at structure works out.

Sometimes, you just have to power through and start writing even though you have no confidence.

The best advice I have is to abstract out every key point in a work, keeping the list in order—a sort of outline-after-the-fact. In that form, any organizational wobbles should become clearer and therefore remediable. Coming up with poor structure in the first place isn’t a sin; sticking with it once it proves unwieldy or unclear or simply unsuitable is. All the fine writing in the world can’t make structural weakness into strength. That’s like adding lots of fancy details to a house with a crumbling foundation: eventually, the whole thing will tumble down around your ears.

Dishonesty in writing is the one unforgivable sin. If we intend to deceive our readers, the writing has no legitimacy. If we hide the truth from ourselves in order to cut corners, we allow our own folly to mislead others. Either way, there is no remedy available except to begin again with better intentions. Writers live within a basic compact with readers, and dishonest behavior breaks faith with them. Alas, we are awash in dishonest communications these days, which some commentators have dubbed “the misinformation age.” It is worse than that, actually a “disinformation age,” meaning that the spread of misinformation is intentional and aimed at doing harm. Neither our governing institutions nor our civil society can survive for long under such an assault on truth. Every part of an editorial or report can be perfectly written, but if the thing is corrupt at its very center, it can come to no good. All the more reason for those of us of goodwill and moral intent to cling to honesty as tightly as we can.

You will notice that this elaboration is only six, not seven, items long. If you’re really paying attention, you will notice that the skipped sin is Worry, the first on the list. What gives? Worry is in a sense outside the writing process, too often stopping it before it can begin. We worry about a host of potential negatives when we write. Will my teacher like it? What sort of grade will it get? Will I get likes on social media? Can I really do this? Do I have the right to do this? Have I really figured this out? Do I need to give it more time? Why do I feel so inadequate? These are the questions posed by Gail Godwin’s Watcher at the Gate, the voice of doubt and worry and anxiety trying to prevent writers from writing. That’s why worry was first on the list: if it wins, all the others are moot. You cannot let worry win. There are no easy formulas for achieving that. Sometimes, you just have to power through and start writing even though you have no confidence. Push worry aside with extreme prejudice. Or a bulldozer. I find that swearing helps, but that may just be me. Just start. Push one word onto screen or paper, then another and another. It often gets easier as the words pile up. If not, keep slogging forward. The best way to defeat worry long-term is to finish a project and then another and another. To do that, you have to start, however formidable the task seems. You know you can. You’ve done it before. And you’re about to do it again.

__________________________________

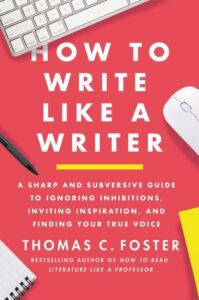

Excerpted from How to Write Like a Writer: A Sharp and Subversive Guide to Ignoring Inhibitions, Inviting Inspiration, and Finding Your True Voice by Thomas C. Foster, available via Harper Perennial.

Thomas C. Foster

Thomas C. Foster, author of How to Read Literature Like a Professor, Reading the Silver Screen, and How to Read Poetry Like a Professor, is professor emeritus of English at the University of Michigan, Flint, where he taught classes in contemporary fiction, drama, and poetry, as well as creative writing and freelance writing. He is also the author of several books on 20th-century British and Irish literature and poetry.