This Must Be the Place: On the Transcendent Refuge of the Musical Past

Dawnie Walton Searches for Representation in Rock and Roll

Last Christmas, our first as a married couple, my husband once again proved he’s my person by lacing me with a top-of-the-line CD player—a component piece named like a cute robot from an ‘80s movie: the Yamaha CD-S300.

“It’s wild how hard this was to find,” Anthony said, but already I was racing to a storage closet in the next room, pulling down my old Case Logic binders.

I flipped through the pages, running my hands over precious artifacts from a previous life: the silvery discs I hadn’t been able to play in years (ever since they stopped making laptops with the appropriate drives), the thick and artful booklets that paired with them, the occasional fading concert ticket.

I have most of this music sliced and diced on various Spotify playlists, so why do I hold on so tight to the hard copies? Maybe it’s because they remind me of a time I felt deeply connected to music as a full sensory experience—as not only aural, but visual. Tactile, even. Yes, I love that I can see my favorite artists whenever I want, on YouTube or Vevo or Instagram or any other service my devices can access… and yet I also remember the music-driven heydays of MTV and BET, when video premieres were scheduled primetime events—when you couldn’t hear a song without instantly seeing a flash of the imagery attached to it.

I miss the old ways we’d bond with music at the crux. The push and pull inside a packed, sweaty club (an experience I’m not sure when—or if—anybody will get back, post-pandemic). The mixtapes we’d so thoughtfully curate for our crushes and our BFFs, hand-lettered in Sharpie we’d take care not to smudge. The phases of fashion and beauty we’d test against our skin, reflecting the vibe of our chosen genres. The afternoons we’d spend scouring the used CD bins at the local indie record shop, on the hunt to discover anything that—get this—looked like it sounded interesting. And the art-designed liner notes we’d gingerly unfold from their hard plastic shells, studying the lyrics in time with the music until each song lived as we thought that it should: burned onto our very souls…

So anyway: After I finished poring over the CD binders, I showed off for Anthony the crème de la crème—boxed sets! Among them, a Clash collection I’d scored off a Bed-Stuy stoop one lucky summer day, and a Sire Records four-disc compilation I don’t even remember how I got, and, inside a sturdy white box covered with raised lettering, all eight of Talking Heads’ studio albums. I cradled that last set with new reverence, and felt the past and the present converge.

*

Back in 2013, I was at the bitter end of my previous marriage. Nights out seeing live music or DJs had marked the early days of that relationship, but on this particular evening, maybe struggling to connect with some lost piece of myself, I’d been home watching a DVD screener copy of 20 Feet From Stardom.

Five minutes in, a clip from Talking Heads’ 1984 concert film Stop Making Sense popped up on the screen. There was David Byrne with his guitar at center stage, his strange movements still so delightfully familiar to me from the videos for “Burning Down the House” and “Once in a Lifetime”… and then my attention shifted to the left of the frame, to the two Black women singing and dancing carefree.

Now, I’d always been aware of the soulful voices punching up “Slippery People”—as a Talking Heads fan, I had sung along with them countless times. But seeing those women set off my synapses. Their names, I would later learn, are Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt, and on screen they captivated me with their microbraids and gray short sets and boldly painted lips; with their high energy and their joyful commitment to this funky-artsy rock & roll. They look like me AND they love this sound?!?

In my younger years exploring alternative music, a centered reflection of my Black-girl self was a vision I had yearned to see, the thing that would have eased my anxieties over enjoying this music. Watching Mabry and Holt, then, I felt thunderstruck, compelled by an urge to stick my hand into the past and nudge one of them to center stage beside Byrne for the rest of the show.

For weeks afterward, the broad strokes of an image—two outwardly opposite artists, sharing a mic and a spotlight in a bygone era of weird rock & roll—would not let me go. I’d think about this duo on the subway. While loading the dishwasher. While sitting in work meetings that could have been emails. While wasting my time on terrible dates. At this point of my life, I had not written fiction for a very long time and had certainly never attempted a novel. But I had this pair of fuzzy figures lingering in my mind, and I had a heart in need of healing. By the end of that year, I decided it was time to start—to turn up the amps, to focus the lens, to dig back in time toward my inner romantic, before she too became obsolete.

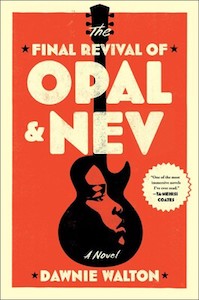

The resulting novel, The Final Revival of Opal & Nev, imagines a rock heroine who might have been my favorite artists’ favorite artist, and whose poster I’d have loved to pin on my bedroom wall: the Black protopunk heroine Opal Jewel. In the seven years I worked to bring her to life, I found out about so many women who’d been marginalized in rock, and devoured their music where I could find it online. But no research helped me feel closer to Opal’s world, her friends, her fans, and her conflicts quite as much as the time I spent dreaming into visuals and artifacts.

In my younger years exploring alternative music, a centered reflection of my Black-girl self was a vision I had yearned to see.

With colored pencils, I cobbled together sketches of her stage looks, inspired by fashion and nightlife photographs I sourced from the early 1970s. I looked at iconic album covers and found I could see Opal & Nev’s look too, down to his swoop of red hair and the glittery makeup smudged across her eyes. I picked up pieces of them from things I saw around Brooklyn—the décor inside the bar Ode to Babel, where Jean-Paul Goude’s iconic image of Grace Jones with her dangling cigarette hangs beside one of Aladdin Sane-era David Bowie; and the paintings and performance-art video comprising the Brooklyn Museum exhibit “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85.”

I saw their eclectic devotees in early-‘90s pictures and flyers from Einstein A Go-Go, the Jacksonville Beach all-ages dance club where punks met goths met skaters met me, a teenage Black girl who wasn’t quite sure yet where she fit in, other than facing the wall of speakers. And when building the novel’s violent climax, I dredged up the symbol most closely connected to Jacksonville’s own Southern-rock standard-bearers, Lynyrd Skynyrd: the Confederate flag, as emblazoned on stages and records and T-shirts of obnoxious fans hiking up their lighters and screaming “Free Bird!”

Those images fed the louder aspects of my story and characters. But I felt the quiet of them in visuals too. Like in this portrait series starring trailblazing women in new wave and punk, shot by rock photographer Michael Putland at a London hotel in 1980. Across several frames I saw Siouxsie Sioux, Debbie Harry, Chrissie Hynde, and the Slits’ Viv Albertine laughing and mugging in a cozy-looking line. But perched together on a love seat in front of them, the two Black women—whose names and music I tragically didn’t know at the time I first saw these—gave off a different vibe, or so it seemed.

Were Poly Styrene (of X-Ray Spex) and Pauline Black (of the Selecter) more serious than their contemporaries on that day? Were they stiffer, perhaps a little wary? Did they lean into each other at Rutland’s direction, or as a gesture of connection and affinity? Or was I projecting my own complex emotions? Of course, I could never assume what another real-life person frozen in a fleeting moment was thinking or feeling. But for the purposes of sparking my imagination, gazing at these photos got me asking questions about my fictional idol’s interior life and how she might have played similar scenes.

*

I spent seven years gazing into the musical past, but nothing has pulled me back to the 21st century like having this novel out in the world. My favorite platform, of course, is Instagram, where I engage with the lovely strangers who’ve read Opal & Nev and delight me daily with their creative posts. Here is my novel’s cover, displayed on an e-reader and nestled in the curve of a guitar; there is the Book of the Month edition, poised to spin atop a turntable… Having thought so hard and so long about the sway of images connected to music, it now feels surreal and incredibly humbling to see how this book has sparked some cool visuals too, floating around up there in the cloud.

But now and then, whenever I want to feel grounded, I sneak a break from the screen. I keep a first-edition hardcover copy on my work desk, right next to my laptop. Between emails and posts I pick it up, to feel its comforting weight and the texture of the jacket. To flip through the pages and try to catch a whiff of that wonderful scent I know it’ll carry, once it transforms to an artifact for somebody else.

As for the other hard copies, we’ve displayed them like a real bookstore might—with a few turned out among the spines, so that Opal’s profile inside the guitar is front and center. These shelves live in the same room as a vintage typewriter and my new CD player, on which I’ve only played one disc so far—a mix that Anthony made for me, full of songs we’d planned to play at the 2020 wedding celebration that Covid forced us to cancel. I’m holding out for the lazy day I can spend in this room curled up with my husband, with my books in view and my music going. Liner notes in one hand, a cup of tea in the other. All of my senses, fully engaged.

__________________________________

The Final Revival of Opal & Nev is available from 37 Ink, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Dawnie Walton.

Dawnie Walton

Dawnie Walton is a fiction writer and journalist whose work explores identity, place, and the influence of pop culture. She has won fellowships from the MacDowell Colony and the Tin House Summer Workshop, and earned her MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Previously she worked as an executive-level editor for magazine and multimedia brands including Essence, Entertainment Weekly, Getty Images, and LIFE. A native of Jacksonville, Florida, she lives with her husband in Brooklyn.