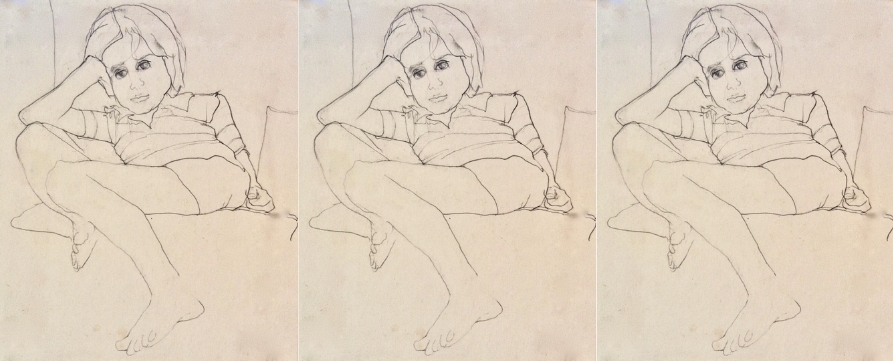

Paul La Farge by Wendy Walker, 6.10.1978

I met Paul 45 years ago, in January 1978.

I was on my way out the door with a suitcase when the telephone rang. The phone sat on a shelf beside the door so I could answer without putting my suitcase down. Tom La Farge, the friend of a friend, introduced himself and asked if I would join him at home for a glass of wine. He sounded nice, so I accepted, thinking: I will take a morning train.

Tom’s apartment was eight blocks away from mine on West End Ave. We sat and talked in his living room beside a wall lined with books. A couple of hours into the conversation, a sound of whistling floated out of a room further back in the apartment, down a dark hall. It was seven-year-old Paul, fast asleep, whistling the theme from Star Wars.

*

Towards midnight I went home. While I slept the legendary blizzard of January 20, 1978 swept into the city and by the time I awoke a swirling white silence had halted all vehicles on the East Coast. I never did take my train. Tom and I continued to meet and later that week I went back to his apartment to have dinner and meet Paul.

A thin and very tanned little boy knelt on the carpet surrounded by Lego bricks. Tom poked his head out of the kitchen and introduced us. When I greeted Paul, he fixed me with an intensely appraising glance. I don’t remember what he said. All that I remember is that coldly critical gaze. In a flash I heard myself thinking, This boy is going to be a writer.

*

In the years that followed, whenever I told Paul about that flash of foretelling, he would show great interest, but when I offered to tell him what I had “seen” he begged me not to. A few months ago, when I brought up the subject of our first meeting, he said he had always assumed I had thought he would become an architect, because of the Legos.

*

His childhood tastes were sometimes idiosyncratic. In the spring of that first year, Tom’s mother—Granny—came for a visit and took Paul out for an afternoon. They stopped at a toy store to buy him a present. Paul made a beeline to the shelf that held what he wanted: a black Barbie doll. Granny was upset. She pleaded with him, “Wouldn’t you like a nice gun?” But Paul insisted.

*

As a child Paul read voraciously, always science fiction and fantasy. His favorite writers were H.P. Lovecraft and Michael Moorcock. When he was eight or nine, he decided he wanted to be Chthulu for Halloween. I hadn’t read Lovecraft so Paul had to explain to me what was needed.

We got him a dark leotard and tights as a base. Then we took a bunch of surgical gloves, the pale translucent beige kind, and cut off their fingers and thumbs. These we glued all over the front of his torso so they could flap about like tentacles, and gave them an inky wash of ghastly blue. Then I painted his face in a blue and silver checkerboard with stage make-up.

*

When Tom and I worked on our writing exercises, a daily practice, Paul always found a way to listen in, and sometimes wrote with us. We would set a literary problem, write, and then read each other our results. Later, when Tom and I were working on our own and each other’s novels, consulting and editing, Paul always found himself a spot in the room, where he huddled with a book, or did his homework, or just listened.

His interest in these discussions—which sometimes grew tense—was palpable. When he was a little older, Tom would pour him a small glass of wine with our candle-lit dinners, and the three of us would discuss literature and writing with energy and joy. To my mind, these dinners, which continued until Paul went off to college, constituted our happiest hours together.

Often when I was writing at my desk, which was in the bedroom that Tom and I shared, Paul would curl up on the bed behind me and read. Sometimes I would turn around to find that he had fallen asleep. On one occasion when I was reading in bed, Paul came in to show me something he had written. I was particularly impressed with the way he had wound up the piece.

I don’t remember what it was about, but in the last page or so the music of his language had conspired to mimic the narrative content. When I pointed that out to him, he became visibly excited and rushed off to get back to work.

*

He was ten or eleven when we got a first taste of his devastating wit. My mother, who could be needy and annoying, had come for a visit and was sleeping in his room. Among her belongings he noticed the book she had brought along, a biology text titled Viruses. Paul glanced at it and remarked, “Roots to your mother.” Tom roared and I couldn’t help but join him.

*

In the summer of 1985, when Paul was fifteen, we rented an apartment in Paris on the Rue du Cherche-Midi. The rental was for eleven weeks and had two bedrooms; we took Paul and his friend Brian Maxey with us. Brian had been avidly reading James Clavell’s Shogun and Paul followed suit.

Since the boys were not interested in going round to museums with us, Tom taught them how to use the Métro and they took off to explore the city. Somewhere they found a store that sold toy samurai swords made of wood. They each bought one and spent many afternoons as medieval samurai, hacking away at each other in the Bois de Boulogne.

One day when Tom and I were wandering around the Ile de la Cité, we came upon an antique store that sold pieces of Japanese armor. We also noticed the topless sunbathers enjoying the little park at the tip of the Ile, and when the four of us reconvened at the apartment to make dinner we reported what we had seen.

The following morning, while Tom and I were writing, Paul came in to say, “Dad, you know that armor store you found on the Ile de la Cité? Brian and I are going to try to find it.”

Brian left us after three weeks to rejoin his own family and Paul started karate lessons at a school housed in a decaying mansion on the Left Bank that had been built by Catherine de Medici as a seminary for young women. Paul was the youngest student there, but he was taken under the wing of an elderly Japanese woman who was more or less the same size. He also started to draw a wonderful cartoon called Brian the Ninja in which the character of Brian, a spherical ninja who vanquished his enemies with the combined force of his size and the element of surprise, performed feats of valor in tiny line drawings full of clarity and wit.

*

Paul’s creativity mainly ran in the verbal vein but on one occasion, when he was perhaps eleven or twelve, he brought home a sculpture he had made in shop class. He had constructed a tall solid pyramid out of wood. From the pyramid’s tip, a copper filament floated out into the crown of a boy also fashioned from copper wire. He seemed to be flying in the breeze.

I was deeply impressed and touched by the sculpture’s honesty and beauty. Paul had found a way to show that the security of his attachment to abstract form gave him ecstasy and freedom.