2018

Minerva Hunter stumbled into the protest by accident, a cacophony of voices swerving her off her path. All around her, bundled into jackets and scarves, other people hurried in ones and twos toward that sharp static swarming call. It was mid-November, a Saturday, and it sounded to Minnow’s ears as if all of Paris had descended. Curious, she followed the others down a narrow side street and then out onto a boulevard. It was densely packed, swollen with bodies. Children perched on their parents’ shoulders, heads swiveling, faces bewildered and pleased. Minnow’s eye picked out a bristling forest of placards hand-printed in French, long swooping banners, and far ahead, tall marionette puppets leaping and jerking above the crowd. The air was bright with excitement, as if everyone had shown up to the same surprise party.

Minnow knew that Paris was a city people mythologized, but she herself hadn’t brought a lot of fantasy to it. She had taken a job here because the job had presented itself at the moment in which her American life dissolved. Had it been located on another planet, she would still have unhesitatingly agreed. But when she’d landed in Paris, in September, the city had been drenched in sunlight, and she had found herself sliding into it like a warm bath. Her first day, she’d walked through the sweeping corridor of trees that marched down the southern side of the Jardin des Plantes, and the beauty had shocked and soothed her. Oh, she’d thought then: Paris. Now, coming across this strange and brilliant crack in the city’s nonchalant quiet, she thought again, Oh, and the surprise curled through her like pleasure.

Minnow pressed in closer and bodies shifted to permit her entrance. She brushed up against puffy down jackets, gleaming leather shoulders, bare arms and yellow construction vests. She recognized these from recent news broadcasts in which the French was spoken too quickly to catch but the day-glo yellow was unmistakable. The protestors were even calling themselves the gilets jaunes, or yellow vests—or maybe they were called that by others, she wasn’t sure. She had seen them on TV more and more of late. The images slid past her, meant nearly nothing.

“Excusez-moi,” Minnow said hesitantly to the nearest puffy jacket. It turned, and she found herself cheek to cheek with a woman in her sixties. “Qu’est-ce qui se passe ici?”

The woman was startled into a smile that grew broader as she took Minnow in. She answered Minnow’s question with her own: “Vous êtes d’où?”

“America,” Minnow said, a little apologetically, and the woman laughed.

“Ah, okay, America.” The woman launched into a fast-paced explanation—something about a Facebook post, a video, a call to gather. Truckers, but also regular citizens, mothers and fathers, the workers. People who were hungry and angry, to whom nobody was listening. The woman made a sweeping gesture, triumphant. The gilets jaunes were gathered not only here but outside of Paris as well: partout, partout! “Vous voyez, Madame!” she cried.

She spoke even faster, and Minnow listened carefully but understood only the disdain, anger, sorrow. The woman interrupted herself when the man beside her started to shout a rhythmic phrase. She picked up the chant with swift efficiency and all at once everyone was shouting it, creating the effect that had drawn Minnow in in the first place, that of total concentrated synchronicity: “Macron démission! Macron démission!”

Glancing around, Minnow gave up estimating how many were present. Even as the crowd shuffled forward, it joined itself to yet another mass of bodies creeping along the avenue ahead, and the confluence forced all movement to a standstill.

Even ground to a halt, the crowd was like a great machine coordinating all its parts. People shouted and chanted and greeted each other. “La Marseillaise” started playing, coming from an unknown direction. After a few moments of bobbing on tiptoe, trying to see over the shoulders in front of her, Minnow grabbed the side of the nearest lamppost and pulled herself up onto the narrow metal lip where the lamp’s wide base narrowed into its pole. Wedging her sneakers into the metal furrows, she clutched the pole tightly to keep from slipping and stared out over the crowd. She realized for the first time that she had emerged onto the Champs-Élysées, the long avenue leading up to the Arc de Triomphe. Turning to look in all directions, she made out the metal-and-glass bulge of the Grand Palais in the distance, and farther still, rising up on the opposite bank, the delicate lace of the Eiffel Tower.

The large marionettes were approaching down the aisle of the avenue, and people moved aside to make room. Lady Liberty beckoned with her long arms, torn bedsheet streamers floating from her wrists. The wind buffeted her, forcing the puppeteer to move side to side, laughing, as he tried to keep her upright. Minnow saw that he was a young man in a leather jacket with the collar turned up, dark hair falling into his eyes in messy tangles. He was almost directly beneath her now, his face upturned. She lowered her chin and as their eyes met unexpectedly, Minnow realized with a jolt that she recognized him. It was Charles Vernier.

Charles was a fellow teacher at the university where Minnow worked. He had only recently graduated from it himself. Minnow reassured herself that this was why the students all loved him; he had been one of them not so long before. It irked her how much they adored him, students who were impassive and unimpressed in her own classes, who intimidated her a little bit with their European sophistication. She imagined that they looked down on her as a boring, nearly middle-aged (no, say it! middle-aged!) American woman who had appeared after their semester had already begun, to cover literature classes they didn’t particularly care for. Charles, on the other hand, exuded cool. He was in the Communication and Media Department, which sounded much more au courant than simple, stuffy English lit. When he taught, he rested one narrow blue-jeaned ass cheek on his desk, long legs sprawled out, and the students hung on his every word. Passing his classroom once, she had seen this—the girls who had packed the front row to bat their eyelashes at him, the boys as well. Her students sat in the back and couldn’t be lured any closer.

The other teachers said Charles’s family name, Vernier, as if Minnow might recognize it. This told her that he was not only wealthy, he was aristocratic. Even worse, Charles had the good fortune to be attractive, which irritated Minnow the most of all his sins. How devoted would his students be, she asked herself, if he were middle-aged, middle-class, and ferociously ugly?

Though she had met him briefly at a faculty welcome dinner and seen him from time to time in the halls, they had never spoken. She had felt as if she’d never registered for him, a state that she was sensitive to, as she was often overlooked: her quietness, her stillness, her way of folding herself into herself so that eyes would go right past her. These things were her fault, she knew, and it had only become worse since the incident at her previous job, after which she had been fired. This was how she thought of it: The Incident; though it was in truth not one event but a chain of them spilling outward into the public eye. Now she caught herself practicing a particular way of standing in which she sank her chin into her shoulders as if trying to disappear entirely. Charles, on the contrary, entered every room to the turning of heads. It surprised her to find him here, mixed in with a cheering crowd, content to be one of many.

His eyes firmly fixed on hers, she saw the exact moment in which he recognized her. His face went blank with surprise and he lost control of Lady Liberty, who soared high, seized by the wind. Minnow felt a rush of embarrassment, as if she had been caught somewhere she didn’t belong. She jumped down from the lamppost into the crowd, her heart pounding. What did it matter, anyway? His opinion meant nothing to her; she didn’t even know him. She turned her back on him and pushed off into the sea of bodies, seeking the safety of anonymity.

__________________________________

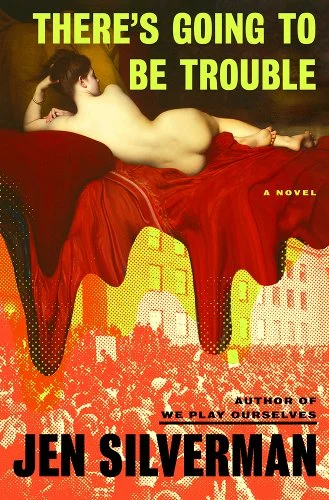

From There’s Going to be Trouble by Jen Silverman. Used with permission of the publisher, Random House. Copyright © 2024 by Jen Silverman.