Across the hall lived a woman named Helen. Lucy watched her from the hole in the door. She watched strange and beautiful young women coming and going from Helen’s apartment. She watched Helen carrying sacks of cold beer, sweating on the way up the stairs, moving a new armchair in through the door, leaving in heavy brown shoes, clomping out and into the world. Lucy had been watching Helen for some weeks, on tip-toes, her eye pressed to the peephole. She tried to keep herself from blinking, for fear of missing something, though Helen was often gone and there was nothing to see. Sometimes, in the evenings, Lucy stood purposefully in the doorway when she knew Helen collected the mail or took out the recycling and would lean against the doorframe and wait for Helen to come out, and Helen would wave a tight, firm wave and smile thinly and go down and pedal away on a green bike.

Helen was often busy and away from home. Lucy was home all the time. She had nowhere to be. She’d come to Denver not knowing anyone and not having anything to do. She’d come to find Helen, but that had been easy, and now that she was here, she wasn’t sure what came next. Denver was her home now and she wanted to make something of it. But the city was strange and too quiet. All day long she waited for Helen but when Helen arrived, she couldn’t think what to say. Days were long, asphalt-smelling, hot to the touch but with something in the way, a hand on an oven door. To pass the time Lucy applied for work in different places, restaurants and hardware stores and delis and a bowling alley, and none of them called her back. She had no experience.

Everything was closing. Shops boarded their windows and doors and at night people lit fires in alleys and took bats to the sides of cars. Everyone was worried and bored. At night, Lucy put rags along the windowsills to keep out bad air while she slept.

It was early summer and hotter already than last summer, which was hotter than the summer before that. Fans whirred in all the rooms and often the sound of the air moving was the only sound Lucy heard. Sometimes a child screamed in the street and sometimes an alarm went off and sometimes the woman upstairs dropped something, a cast-iron skillet or some other heavy thing, but mostly it was the whir of the fan and the buzz of the light above the sink and the tiny steps of mice who lived in the walls around her.

Helen went out, Helen came in. There she was, standing on one leg in the hall, scraping something from her shoe. Lucy squinted with one eye pressed to the hole in the door, the same flush she always felt, a quickening. Helen bending at her wide waist, fussing again with the shoe, a cream leather high-top, cursing quietly under her breath, hair falling into her face.

Helen, Lucy said, but only a whisper, only to herself.

Lucy came to the house, a Victorian situated behind a high school, by stolen car, a 1993 Buick, something her father had bought at auction and left to rust. The car wasn’t missed and neither was Lucy, but there was still the funny sense that she was being followed, tracked, not directly, but from afar, much the way she was watching Helen. A thing her mother did, a thing Lucy had inherited, despite never wanting to be a thing like her. All girls felt this, her mother said once, squeezing a tick from her calf, all girls want to avoid the trap of their mothers, but unfortunately, we’re all in blind servitude to genetics. That’s the way it is.

The mother had thin yellow skin with veins all showing and smelled like overripe fruit. She was stormy and fine-boned, prone to long periods of quiet anger. At night she walked the halls and kitchen, pacing, watching. In the mornings Lucy would find her not having slept at all, just sitting, foot tapping beneath the table, having seen the whole dark night.

It was because of their mother that Lucy’s brother had left, driven west without her, leaving Lucy alone on the High Plains. He hadn’t meant to, he promised over and over to bring her along, but the fact was he hadn’t.

After he left he called her every night as he walked and smoked and explained what he saw in the bright, toppling city. Buildings went up and came down. Flowers were planted and shortly thereafter died. Cranes stood like the birds they were named for, stoic, swaying. No one said hello, though once people had said it was so friendly, this city. In the west the mountains were just like the song, purple, majestic. That was one thing we got right, he said, about America. Over the phone his voice was long and muffled. Sometimes it was difficult to make out what he was saying and Lucy didn’t bother to ask him to repeat it. It was all the same kind of stuff and all she could say was come home, but no, he said, that wasn’t possible. There was always their mother there, just behind the door, breathing, sucking air through her soft, round teeth, waiting to get in.

And then one day he didn’t call. Lucy waited, wondering if something had happened. But he called the next day. I met someone, he said. A friend. But Lucy took that to mean something else. He was so beautiful. He had a face that was always tumbling toward something. Everywhere he went someone stopped to look at him, studied his face, stood close enough to smell him, her brother, Mikey, a wind-strung boy with a face you wanted to kill.

Helen, he said, smiling through the phone. Her name is Helen. You’d love her.

They’d met in the Hotel Chester where Mikey was working, and after that he was with Helen all the time. Sometimes when Lucy called he would tell her he had to hang up because Helen was coming over. Sometimes he wouldn’t answer at all and Lucy had to surmise that he was with Helen and so was too busy and Lucy would be left to sulk and worry alone in her hot, cramped room with the sound of goats bleating in the yard and a table saw jamming in the driveway.

When Helen was only a name, Lucy imagined she was long and gorgeous and smart. She wore pantsuits and lipstick and hornrimmed glasses and knew the titles of all Mikey’s favorite books. She had degrees in French and chemistry and played in a band. She kissed Mikey’s hands and the corners of his mouth. They lay together, shirtless and paint-streaked, in a high-ceilinged loft in the afternoon. The city was swelling and spilling around them, fire hydrants and sticky windows. Everywhere people burst into brilliant flames. This was what Lucy saw when she closed her eyes and thought of Mikey, of the city, of Helen.

But now that she saw her, Helen wasn’t the way Lucy had imagined at all. She wasn’t long or gorgeous and didn’t wear lipstick or glasses. She didn’t seem particularly interested in art and wasn’t particularly beautiful. She was loud and cluttered and brash and walked like a suitcase, like she was being pulled from room to room. She made a lot of noise on the stairs. Her hair was short and blonde and messy, standing like a fin on her head. Her shoulders were wide and her voice had a low, musky quality that reminded Lucy of motor oil. Her music was too high and she laughed in a throaty, measured way, like the joke was always one she’d made. She spent all her time with women and never men. Once Lucy saw her, it didn’t make sense—Helen, or Mikey, Mikey with Helen. Lucy worried she had the wrong place, the wrong Helen. But her brother had been so clear. He’d given her an address. He’d told her to come. And she had, eventually, and too late.

Lucy sat on the floor outside Helen’s door thinking of things to say. She would be back soon enough. It was June and the hallway was stale, too warm. Everything smelled sweet and cheap, like pink soap. Her skin had the tight, dry pull of the thin Denver air. Tomorrow she would be twenty-one, her birthday. She rubbed along the bone of her jaw and wondered if she’d gotten prettier, or if her face had stayed mostly the same.

Light poured down the long hallway, dimpled and rose-colored, the dust from the carpet rising and falling. Lucy tried to catch it in her hand, waved her fingers through. It was lovely and disgusting, all that shimmering, suspended debris. The light now was always orange, the sun always red. Something having to do with ozone, with dust, with particles brought up from the bottom of the ocean. Something to do with the vengeful atmosphere and disappearing grasslands.

You knew my brother, Lucy would say when Helen returned. It was easy enough to say. Simple. The words rolled around in her mouth. Helen’s name and then her brother’s. They were jumbled and loose in there, like teeth. Helen and Mikey. Mikey and Helen.

But Helen was out. Her brother was dead.

Lucy sat in the heat of the afternoon and waited for them both to come back.

__________________________________

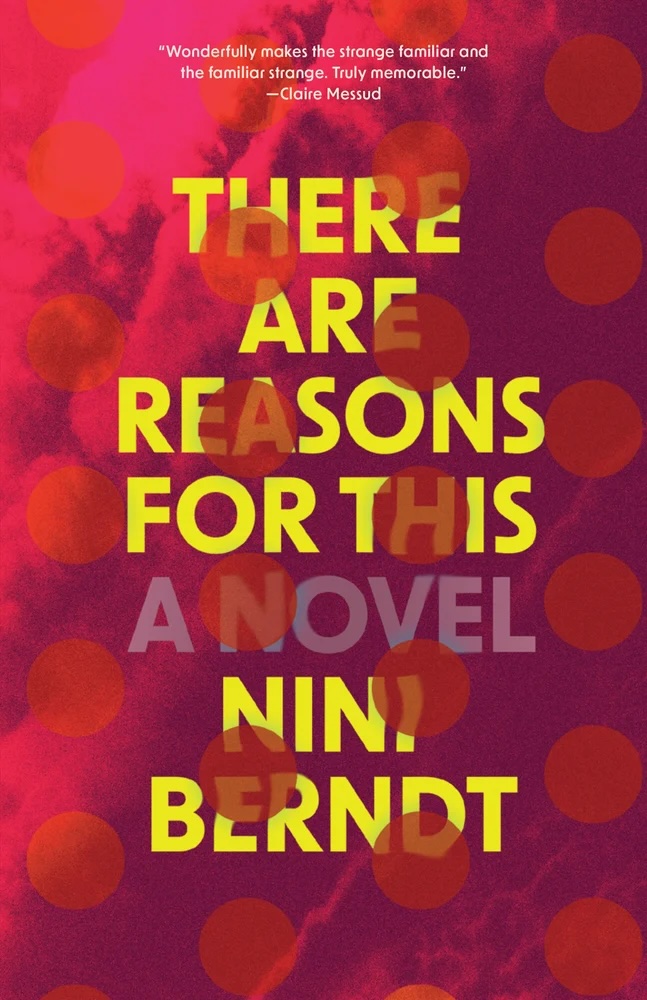

Excerpted from There Are Reasons for This by Nini Berndt. Used with permission of the publisher, Tin House. Copyright © 2025 by Nini Berndt.