Theorizing the Basis of Our World: A Reading List on Quantum Reality

Heinrich Päs Recommends Manjit Kumar, Jim Baggott, and More

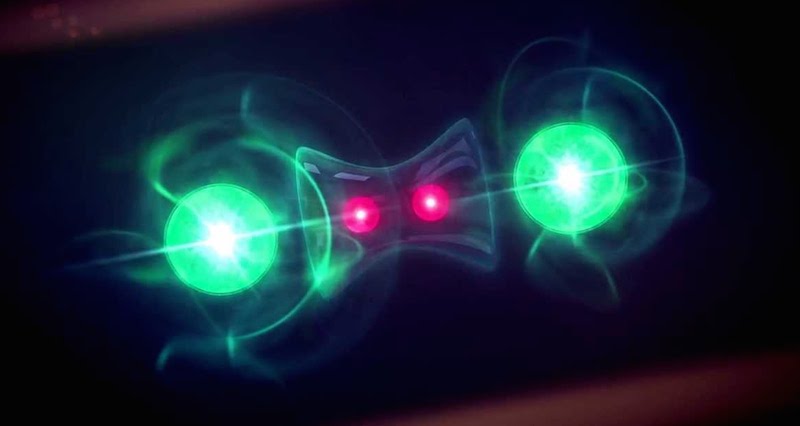

Quantum Mechanics is the science behind nuclear energy, smart phones, and particle collisions. Yet, almost a century after its discovery, there is still controversy over what the theory actually means. The problem is that its key element, the quantum-mechanical wave function describing atoms and subatomic particles, isn’t observable. As physics is an experimental science, physicists continue to argue over whether the wave function can be taken as real, or whether it is just a tool to make predictions about what can be measured—typically large, “classical” everyday objects.

The view of the antirealists, advocated by Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and an overwhelming majority of physicists, has become the orthodox mainstream interpretation. For Bohr especially, reality was like a movie shown without a film or projector creating it: “There is no quantum world,” Bohr reportedly affirmed, suggesting an imaginary border between the realms of microscopic, “unreal” quantum physics and “real,” macroscopic objects—a boundary that has received serious blows by experiments ever since. Albert Einstein was a fierce critic of this airy philosophy, although he didn’t come up with an alternative theory himself.

For many years only a small number of outcasts, including Erwin Schrödinger and Hugh Everett populated the camp of the realists. This renegade view, however, is getting increasingly popular—and of course triggers the question of what this quantum reality really is. This is a question that has occupied me for many years, until I arrived at the conclusion that quantum reality, deep down at the most fundamental level, is an all-encompassing, unified whole: “The One.”

The list below contains 12 books that I find particularly enlightening about why quantum reality makes sense, what the counter-arguments are, and what quantum reality is.

*

Manjit Kumar, Quantum: Einstein, Bohr and the Great Debate about the Nature of Reality

To understand how the controversy about quantum reality started, it makes sense to look back at the early history of quantum mechanics, and the quantum pioneers’ struggle to make sense out of the new theory. Manjit Kumar’s book tells this story as a captivating narrative, starting from Max Planck’s discovery that the electromagnetic radiation emitted by matter required that it was emitted or absorbed in bits, discrete units, or “quanta,” to the famous debate between Einstein and Bohr, always focusing on what quantum mechanics meant for our notion about what is real.

Jim Baggott, The Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments

A wonderful alternative, companion or complement to Kumar’s book is Jim Baggott’s The Quantum Story. Whereas the former delivers a consistent story of the development of quantum mechanics in the first half of the twentieth century, the latter concentrates on the glorious moments of the most important discoveries and also includes topics such as modern particle physics, the Hawking radiation emitted by black holes, and the Wheeler-DeWitt equation for the quantum wave function of the universe.

Adam Becker, What Is Real?: The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics

In the years following the Einstein-Bohr debate, most physicists accepted that Einstein was wrong and Bohr was right. Moreover, after the outbreak of World War II and subsequent discoveries in nuclear, particle and solid state physics, research concentrated on applications of quantum mechanics rather than on the foundations of the theory. Adam Becker’s book zeroes in on the dissidents questioning Bohr’s orthodox view, and how they encountered a toxic blend of hostility and dogmatic pragmatism from their peers. It describes how these quantum dissidents, among them David Bohm, Hugh Everett, Heinz-Dieter Zeh and John Stewart Bell, saw their careers ruined or had to pursue their work on the meaning of quantum mechanics more or less secretly in their free time.

Olival Freire Junior, The Quantum Dissidents: Rebuilding the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (1950-1990)

Olival Freire Junior’s Quantum Dissidents tells this story from a slightly different angle. It is a little more scholarly but still a great read, and it points out how the dissidents’ questions inspired the new research field of quantum information that is currently entering the stage where quantum computers are starting to outperform classical computers.

David Kaiser, How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture and the Quantum Revival

Kaiser’s book focuses on a small group among the quantum dissidents, especially a gang of freewheeling physicists in Berkeley that called themselves “Fundamental Fysiks Group”. While the group explored some quite outlandish topics such as parapsychology, they also for some time included John Clauser who conducted the first experiment demonstrating what Einstein had called “Spooky Action at a Distance,” puzzling correlations between entangled particles that may be separated by large distances, and who received the 2022 Nobel prize.

Nick Herbert, Quantum Reality: Beyond the New Physics

Another member of this group was Nick Herbert, whose wrong claim that such “Spooky Action” allows for faster-than-light signaling inspired the “No-Cloning-Theorem” in quantum information science, that is prohibiting to copy arbitrary, unknown quantum states. Herbert also wrote a book that actually was titled Quantum Reality. It offered one of the first discussions of various conflicting interpretations of quantum mechanics. And while the book doesn’t do full justice to the Everett interpretation, it contains one of the rare discussions of what quantum entanglement implies when being applied to the universe: “The world is an undivided wholeness”.

Jim Baggott, Quantum Reality: The Quest for the Real Meaning of Quantum Mechanics- A Game of Theories

Quantum Reality is also the title of a more recent book by Jim Baggott. Similar to Herbert’s book, Baggott’s more modern counterpart discusses many interpretations of quantum mechanics, and the respective notions of reality they infer, and reviews the arguments both in favor and against these interpretations. At the end Baggott isn’t convinced and remains skeptical about a realistic interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Coming back to “Spooky Action at a Distance,” George Musser is opening an entirely new can of worms: What does the strange correlation of faraway things imply for our notion of space? Musser’s journey leads him to the most cutting-edge research in string theory and quantum gravity, that aims to show how space and time may be stitched together from quantum entanglement. His conclusion: “spacetime is doomed.”

The most obvious and straightforward but equally bizarre and controversial approach to adopt the quantum-mechanical wave function as reality is Hugh Everett’s “Many Worlds Interpretation”: If the quantum-mechanical wave function allows for two or more alternative events, all of them happen, albeit in parallel realities. Everett was an exceptional person, both unconventional and ingenious, and this is beautifully illustrated in Peter Byrne’s biography.

David Deutsch, The Fabric of Reality

David Deutsch is one of the pioneers of quantum information science, and his book is an unadorned plea for a realistic wave function in the shape of Everett’s many worlds interpretation. According to Deutsch, “It is the explanation—the only one that is tenable—of a remarkable and counter-intuitive reality.” Deutsch goes on and relates this view to interesting and passionate discussions about philosophy of science, quantum computing, the unreality of the flow of time and the significance of life.

Sean Carroll, Something Deeply Hidden: Quantum Worlds and the Emergence of Spacetime

Carroll’s book starts with a credo: Quantum mechanics should be understandable, even if it suggests a distinction between what we see and what really is. He continues with an advocacy of Everett’s Many-Worlds-Interpretation, and finishes with a line of argument on why an understanding of quantum reality is important: it helps us to make sense of the exciting new approaches to quantum gravity and an emergent spacetime as a consequence of quantum entanglement.

David Wallace, The Emergent Multiverse: Quantum Theory According to the Everett Interpretation

Explaining what reality is isn’t a job exclusively for physicists. Philosophers have at least as much to say about the topic, and David Wallace does so. “The Emergent Multiverse” surveys Everett’s interpretation from the perspective of philosophy, and does not shy away from rather abstract topics such as the lessons to be learnt from Everett about statistics and probability. Most importantly, it conveys an important message: The “many worlds” of the Everett interpretation aren’t fundamental, they emerge from a more fundamental, unique quantum world.

__________________________________

The One: How an Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics by Heinrich Päs is available from Basic Books, a division of Hachette Book Group.

Heinrich Päs

Heinrich Päs is a professor of theoretical physics at TU Dortmund University in Germany. He has held positions at Vanderbilt University, the University of Alabama, and the University of Hawai’i and has conducted research visits at CERN and Fermilab. He lives in Bremen, Germany.