I climbed the hillock every day since I took the job at Jannatabad Bus Terminal, but that morning my body begged me to head back home. I paused halfway, lungs on fire and veins throbbing in my head, and looked upward.

A hundred yards away, the rusting, ramshackle terminal gate loomed like the first portal of hell. Under the downcast spring sky of Tehran, I stood with my hands on my hips and arched my back to expand my lungs. I thought of a wisecrack Hamid Fadavi had made in our first meeting: “You’ll always know a good bus driver by his flat ass.” As soon as this crossed my mind, I was ashamed. Hamid had been languishing in solitary for forty days, refusing food for the last seven of them. With hundreds of bus drivers intending to stage a strike in his support, here I was dragging my feet to the gate and thinking only of his stale joke.

I resumed the climb, but my heart began to race and numbness spread through my legs. It occurred to me that I might be ill. I could simply go home and come back tomorrow with a story about my sickness. I turned to go down.

A group of drivers were marching determinedly up the hill. They had seen me. One of them waved. I waved back and turned around again toward the gate. I pretended to flick some dust off my uniform and started back up.

*

The Jannatabad Bus Terminal stretched from Laleh Boulevard all the way up to the south side of Hemmat Expressway. The city had dedicated this massive plot of land to buses at a time when no one could have imagined that Tehran would extend so far west. Even as high-rises grew up around them, hundreds of the identical auburn vehicles fended off incursions into their asphalt territory. Seen from the hilltop’s vantage point, the buses formed random geometrical configurations, among which wandered uniformed bus drivers like an army of brown ants. In the mornings, the drivers scattered from their social clusters into the vehicles to start the day shift. But today, I saw them form a conglomeration in front of the management premises, located at the eastern edge of the terminal. As I descended the other side of the hillock toward them, I imagined myself shrinking in the eyes of the men behind me.

The drivers huddled in small circles before the building.

Everyone looked better than usual. Their yellowed skins, prematurely wrinkled by the vagaries of Tehran traffic and the effects of chain-smoking cheap cigarettes, had taken on a flush. Their eyes, usually set in dead stares, shone wide and alert. The place was boisterous like a schoolyard. More than half the faces there were new. They had come from other transportation hubs in the city, like the Azadi or Park-e Shahr or Tajrish terminals. But no one was a stranger. Everyone I passed smiled and patted me on the back like we were old friends.

No one was a stranger. Everyone I passed smiled and patted me on the back like we were old friends.

“Yunus!” someone called. I turned and saw Ibrahim waving from inside a small huddle of men. I waved back, and he walked over. In our terminal, his enthusiasm for the strike was unparalleled. He hugged me tightly, like my arrival was the key to his plan’s success. His uniform was carefully ironed, his eyes glinted, and his face beamed. He looked as flushed and fresh as a rich man at the beach.

Ibrahim began to bring me up to speed. Hamid was still on a hunger strike in Evin Prison, in critical condition. The news had come out that morning that he had been tortured, and his arm had been broken. Another jailed union member, in Rajaeeshahr Prison, had an infection in his eye, and the guards had denied him medical assistance.

Before Ibrahim could say more, someone called to him. He broke off and rushed away without a goodbye.

A shriek of microphone feedback shocked the crowd into silence. The terminal felt instantly colder, as though the sound had blasted away all the warmth in the air. The noise hurt my ears.

From the sea of drivers, a man emerged and climbed up onto a makeshift platform. In one hand, he clutched a microphone tightly at his chest. Shading his eyes with the other hand, he looked left and right, and his mouth curled up into a triumphant smile. The crowd of brown uniforms stirred and pressed toward him. I was carried like a stray piece of debris on the surface of a river and ended up closer to the platform than I wanted.

“My dear brothers and sisters,” he yelled into the microphone. So there were women among us. Or maybe he had said “sisters” out of habit. His thick Bushehri accent amplified the shrillness of his voice. A full beard covered his fat face, and the collar of his wrinkled gray shirt was open down to his chest, divulging a mass of chest hair. Farther down, the shirt stretched tautly over the watermelon-size belly that hung supreme over his belt.

As the crowd quieted down, I could hear female voices whispering behind me. I turned and saw two women. I stared at them in awe and tried to think of a gesture that would express my gratitude for their presence in the strike. A man next to them cleared his throat and frowned at me. I swiveled back.

“We all came here this morning,” screamed the man into the mic, “to demand the authorities . . . from the Ahmadinejad ad- ministration to the offices of the Supreme Leader . . . to release our . . . jailed brothers.” He had stumbled three times in one sentence. The drivers around me shook their heads and grumbled, unhappy with this embarrassing start.

“They are jailed,” the speaker continued, “only because they pursued the basic rights every citizen should be entitled to.” At this he halted and breathed noisily. The drivers snickered. Some even booed. I felt for him. His wheezing sounded like mine as I struggled to crest the hill. It was time for him to cede the podium. His pained expression indicated that he knew this just as well as the rest of us.

“The truth is, we all will die before any semblance of what we fight for comes to fruition on Earth.”

“My dear brothers and sisters,” he said, pausing dramatically, “it is my great honor to introduce our speaker for the morning, Davoud Shabestani!”

Admiring moans and an explosion of clapping followed this. I had never heard the name, but I made noises of approval and cheered along with the crowd. A tall, bearded man stepped up onto the platform and stood with composed stillness. The drivers roared even louder. He wore a neat gray suit and an ironed white shirt.

“I am sure you all know Davoud,” the speaker said. “No one has devoted so much time and work, so much energy, to our union. As you probably know, Davoud spent twelve years in prison before and after the revolution. He understands as well as anyone how our jailed brothers feel.”

The speaker handed him the microphone. Clapping erupted again. Davoud held the microphone in a steady grip and impassively regarded the crowd. The man who had introduced him stepped off the stage.

“We have a difficult path ahead,” he began, his tone as somber as his face. “We are all on a journey together, one that will never end. For the path toward justice knows no end. The truth is, we all will die before any semblance of what we fight for comes to fruition on Earth. But we shouldn’t allow this fact to dishearten us, because the destination is here. The destination is now. As long as you walk this path, you are at your destination. I see before me the hardworking men who risk their lives to serve a sublime cause, and this fills my heart with conviction. I don’t need to get anywhere from here. I am where I have always strived to be. Today, standing among you, I feel the mercy of God pulsing through my soul. If you feel it too, then you are where you should be. You are a warrior in our battle against Zolm.”

The crowd was silent. I examined myself to see whether something divine pulsed in me, but I didn’t sense anything. The cold- ness that had set in earlier dissipated as Davoud spoke.

“But what is Zolm? The word of God leaves no room for doubt. Zolm is defying the order of the world. It is the imposition of your preferred order on God’s design. The Quran is unequivocal on those who commit Zolm: ‘The Zalimoun shall never triumph,’ promises Allah. ‘Woe to the Zalimoun from the torment of a painful day.’ My brothers and sisters, we should all look in the mirror every night and ask ourselves, ‘Did I commit Zolm today? Did I interfere with the divine design?’ You don’t need to be well versed in the interpretation of the Quran to know the answer. If you sit in comfort in a ventilated room exploiting a driver who works twelve hours a day in heat and cold, this is Zolm. If your employee demands better health insurance and you call the police, you are a Zalim, a perpetrator of Zolm. If your bank account is swelling and people who work for you go to bed hungry, you are a Zalim.”

Someone shouted something. A round of applause broke out.

Davoud waited out the clapping with a stonelike face.

“Look at them!” Davoud yelled, pointing at something behind the crowd. Hundreds of heads turned at once.

*

In the direction of the gate, where the hillock met the asphalt, groups of uniformed forces had taken up position. It was terrifying how quickly and quietly they had arrayed themselves. The majority of them were police, lurking behind the special guard that formed the front line, huge young men dressed in black, armored from head to toe with only their eyes and mouths visible, like mutated beetles escaped from a lab. The guards held transparent shields and long batons. Plainly clothed militia, Basijis, stood among the police in single-color shirts and cotton pants, brandishing sticks or tapping them on their thighs. They seemed to be the most harmless of the oppressors, yet everyone knew they were the only ones who would be willing to hurt us.

“Look at them!” Davoud spoke forcefully into the mic. “They think I am intimidated. They think their baton-waving thugs and gun-toting cops can scare me off this platform. Listen! I am talking to you back there. You came here to beat up the innocent people who take you to work, who take your children to school every day. You decided to side with the Zalimoun. You are the army of Zolm. I was in the Shah’s prison for five years. This regime kept me in jail for seven years. I have met the death angel in flesh and blood. Come here and put a bullet in my head! I want nothing more than to ascend into the embrace of God!”

As I repeated the slogans of others, adding my voice to the cacophony, I felt that I was levitating, afloat on the nimbus of rage we were shouting into existence.

Davoud stepped down from the platform. The crowd exploded. Cheers and shouts rose from all corners. Men of all ages and stripes yelled and screamed, their faces red, veins bulging on their necks. I jumped up and down, shouting and waving my middle finger in the direction of the guards.

Soon everyone had turned to face the police to yell demands of all kinds at them. Some wanted the resignation of the transportation minister, others the release of political prisoners or accountability from Ahmadinejad. As I repeated the slogans of others, adding my voice to the cacophony, I felt that I was levitating, afloat on the nimbus of rage we were shouting into existence. The special guards came forward, the sun glinting off the slick surfaces of their armor. They brandished their shields and batons. The Basijis followed them. The police shuffled behind like shy children. They formed a half circle around the crowd and trapped us. Behind the line of forces, the buses sat in silent anguish.

From somewhere behind the guards, a man spoke into a megaphone. “My dear friends, I represent the office of the mayor of Tehran.” Boos and insults met this announcement. I couldn’t see who was speaking because the swarm of officers concealed him.

“This morning we had a productive meeting with the members of the city council. We understand you and sympathize with you. We have concluded that your requests should be met, and we are working with the intelligence services to release the jailed drivers.”

The crowd jeered and roared like the man was a bad stand-up comedian. He kept talking, but the noise on our side rose so high I could hardly hear him. I first booed along but then decided to listen more. His muffled words did make some sense. They had bothered to meet and discuss and had sent an envoy to negotiate. The strike had already worked. We could give them twenty-four hours and get back to work, and go on strike again if they went back on their promises. But under the influence of the crowd, my rage came welling back and I started to heckle again. “Liar! Scumbag!” I screamed.

The driver next to me tapped on my shoulder and proceeded to recount the story of the mayor’s brutal response to the schoolteachers’ strike. There was no reason to believe they would treat us any better, he said. I nodded as he spoke. Another driver turned to describe the various occasions when the union had trusted the authorities and later regretted it. I nodded at him too. All the while, the envoy kept screaming into the megaphone. As the minutes dragged on, his insistence began to make some impact. I heard new, fearful murmuring in the crowd. “Maybe we should postpone the strike,” said one man standing ahead of me to another. “They’re all armed. We should negotiate before it gets violent.” Others around me started to echo this. I wanted to join in but kept my mouth shut.

A few men pressed back through the crowd to the platform, jostling and elbowing us aside. They drew to a halt around Davoud. Through a crack in the mass of people, I could see part of his face. He was shaking his head at one of the young men speaking to him. Another man started to talk, but Davoud only shook his head harder. Then he responded, keeping his eyes fixed on the ground. He hardly moved his mouth when he spoke. The men seemed to assent to whatever he was saying and dispersed without speaking further.

Shortly after that brief meeting, new chants broke out from small, dispersed pockets in the crowd. “We are here to root out Zolm!” “Political prisoners must be released!” I thought that the men who had spoken to Davoud must have instigated this. They must have been seasoned agitators who knew how to take the pulse of a rally. The chants spread fast. I went along and joined in without thinking about what I was saying. Soon the agitators had drummed up a fresh surge of rage. I recognized this manipulation, but I couldn’t keep myself from reveling in it.

The envoy, who had fallen silent, spoke again. His barely concealed frustration made him seem pathetic. “It’s a shame you decided to turn down my offer, but I respect your choice. I am not in a position to tell you what you should do. However, I am accountable to the people of Tehran. We can’t let you take the buses hostage. Our brothers have volunteered to drive the routes and serve the stranded people in the streets. Please respect them as we respect you.”

__________________________________

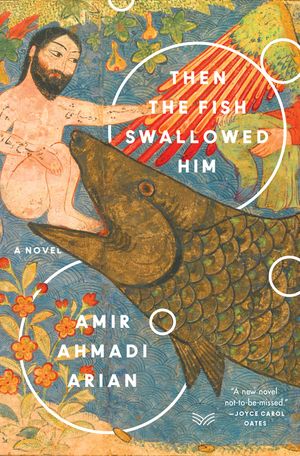

From Then The Fish Swallowed Him by Amir Ahmadi Arian. Copyright© 2020 by Amir Ahmadi Arian. Reprinted with permission by the publisher, HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins.