The Wrong Story: Jeremy Atherton Lin on Writing Love and Politics

“We conspired to look unflinchingly at the messy parts.”

Even the First Lady wanted to party. In her memoir Becoming, Michelle Obama describes the night in June 2015 following the announcement of the opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court case legalizing same-sex marriage across the United States. Increasingly “desperate to join the celebration,” she snuck out with her daughter Malia to view the White House lit up like a rainbow. Too ensconced inside the symbol to behold the effect it was having on revelers gathered outside, she wanted, as she put it movingly, “to see the lights.”

I was living in the UK by then, in a civil partnership with a British man who’d never become eligible to reside in the States on the basis of our relationship. For a period from 1999, before gay marriage and its attendant immigration pathway, he had resided in San Francisco as an undocumented denizen in order to stay with me. Marriage would have taken care of the pickle we found ourselves in. I therefore couldn’t think of anyone for whom the rainbow spoke for more than us. Yet the spectacle seemed distant. I didn’t particularly relate to signs reading “LOVE WINS.” Perhaps the slogan suggested not so much romantic love but something like agape in Christian theology: a desireless, God-like benevolence—love for, not just between, lovers. But how can any form of love take one side in a debate?

During our outlaw years, we never put ourselves forward as public figures. The gay marriage movement needs a pair of poster boys, a friend said, adding: And that clearly is not you two. He meant the unauthorized residency, I guess, and how neither of us is exactly what JD Vance would later refer to as the “normal gay guy.” In the precarity of our togetherness, we had too much to lose, so stole away in the shadows of public debate.

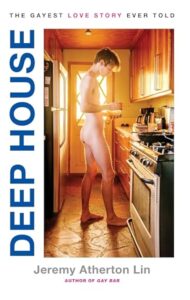

Now, a quarter-century later, I am telling our story—the wrong one. I knew that Deep House, my memoir of our experience, would never be a polemic about emergence into light, but a remembrance of what we found there in the dark. The thing to do if you want to write nuance is find your people: wayward publishing allies. Was gay better before marriage? suggested one editor, who was going through a divorce. We conspired to look unflinchingly at the messy parts. If indeed love won, what a bore to write towards the happy ending. Around the time the book was contracted, a therapist uttered the word surrender to me, giving my book its lodestar. I’d write towards surrender, and how giving in to each other was one form of resisting unfair government systems.

While I began writing, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas made explicit his intention to revisit Obergefell. While I finished, “LOVE TRUMPS HATE” placards were ferried off to landfills as the comeback Republican prepared for a second term. I read of a renewed movement to classify unauthorized residency as a criminal act. A new executive order threatens to disenfranchise sanctuary cities like San Francisco, where my lover overstayed in order to be with me.

If indeed love won, what a bore to write towards the happy ending.

In the wake, a passage by Tennessee Williams has been traveling across social media. It ends: “We live in a perpetually burning building, and what we must save from it, all the time, is love.” The image strikes me because Williams seems less concerned with prevention or extinguishment—“We all live in a house on fire,” goes one of his characters in The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore—than with the continued potential of a love that has escaped the collapsing structure. To extend the metaphor, love might not save the house but needs saving from it, to be kept alive in new forms of shelter before the rebuild.

Hannah Arendt argued that love “is killed, or rather extinguished, the moment it is displayed in public.” To Arendt, love is worldless, and “can only become false and perverted when it is used for political purposes such as the change or salvation of the world.” In 1962, James Baldwin wrote in The New Yorker that to “end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world,” he and other “relatively conscious” people “must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others.” In an open letter, Arendt responded, “In politics, love is a stranger, and when it intrudes upon it nothing is being achieved except hypocrisy.” If Baldwin exalted the beauty, capacity for joy, warmth, and humanity among Black people, to Arendt, these were “well-known characteristics of all oppressed people. They grow out of suffering and they are the proudest possession of all pariahs.”

When I write of alienation, I do explore the beauty and joy to be found in exile. I write of love among outcasts and exclusion as a site of depths. I write from the camp where love is tended, having been rescued from the inferno. Of course, I include the filthy sex. I write the rimming, and make it stinky. I write the music, late dinners, threeways. I don’t write to be transgressive, but do embrace sentimentality, the way Roland Barthes proposed: “Doesn’t ‘a touch of sentimentality’ amount to ‘the transgression of transgression itself?’”

In Arendt’s formulation, the word love is emptied out in the political sphere, or a signifier of emptiness. Even Kamala Harris, vocally on the side of love in various issues, performed this when, in a televised debate, she was asked to identify three virtues in her opponent. She gave only one: “he loves his family,” a backhanded way to diminish the Republican as a man who really ought to step off the public stage. I remain unsure I agree with Arendt, but do see regularly how, when the word love is instrumentalized, it fails to evoke our intimate connections in their vulnerability and complexity. “LOVE WINS” suggests love is an opponent, while in countless pop songs and poems, love conquers each of us. What potent thinking can we bring forward having been well and truly bitten? “To fall in love is to feel the revolution begin,” writes Paul B. Preciado. He proposes that love is a process of “expanding or modifying the limits of what we thought was our own identity.”

In politics, the right story is only the revised version of a wrong one. This makes itself clear to me whenever I research historical forebears. Entering the archive is an agnostic seance, and one must prepare for the gray areas within the illuminations. Jack Baker and Michael McConnell, widely considered the first American gay couple to receive a marriage license, had an open relationship. Richard Adams and Tony Sullivan, the first pair to seek recognition of a same-sex marriage by the federal government, did so because Tony was an Australian seeking an immigration pathway. Marriage wasn’t the binational couple’s chosen cause; they considered it a discriminatory institution.

In the 2003 majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down existing state anti-sodomy laws, Justice Anthony Kennedy used the word relationship eleven times, describing sexual conduct as “but one element in a personal bond that is more enduring.” But the perceived couple at the center of the case were actually two fuckups only casually acquainted. There’s a chance, legal scholar Dale Carpenter has laid out, they weren’t copulating in the first place. The arresting officer may have merely been put off by two sketches on the bedroom wall of James Dean brandishing an outsize erection. Pure camp—though not necessarily nothing to do with love, considering Susan Sontag’s assessment that “Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature.” The winning legal team conjured the image of a lovingly committed couple through omission—almost completely erasing the two alleged fornicators from their narrative.

Kennedy would go on to author the opinion in Obergefell, creating the illusion he’s the gay rights guy. But decades earlier, it was Kennedy who denied Tony Sullivan the right to remain in the States with Richard Adams because he could find no “extreme hardship” in their separation. Tony continued to live undocumented and, in legal terms, a stranger to his partner. Ironically, it may be the love story of Richard and Tony—actual, if imperfect, companions, desperate to be together but not particularly beholden to the institution of marriage—that a rueful Kennedy read into future cases.

No author can control what is read into their text; for this very reason I am devoted to spaciousness, approaching nonfiction something like planting select thoughts in an ungated field, where readers will continue to sow. “One must learn to love,” writes Friedrich Nietzsche. “One must learn to love,” chimes DH Lawrence, “and go through a great deal of suffering to get to it.” bell hooks asserts, “By learning to love, we learn to accept change.” Writing at length is to me always an act of learning and changing, in which authors can strive towards something more dimensional than a platitude on a placard. We can consider expansive forms of loving not through conclusive argument but an openness to ambiguity and mess. In literature, we find one place love belongs: in the furrows, muddy, unknowably deep, where love not only survives, but generates.

_____________________________________

Deep House by Jeremy Atherton Lin is available via Little, Brown.

Jeremy Atherton Lin

Jeremy Atherton Lin is the author of Gay Bar, a New York Times Top Book of 2021 and recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award. His essays appear in numerous places including the Paris Review, the Times Literary Supplement and the Yale Review.