The Writing Conference That Ended in a Russian Police Station

Jessica Anthony's Search for a Thief in a Torn Red Sweater

I’m drunk and on the Nevsky Prospekt, the street that carves St. Petersburg in half, tugging at the sleeves of strangers. I’m trying to explain what a wallet is without using any word in Russian that means anything close to wallet. I say spasiba a lot, and then I say in desperation, “No, that’s not a penknife.” I have been studying Russian for three weeks from a Russian book of grammar printed during the Roosevelt administration. The first one. This is all I can remember.

The Russians look at me sideways. I’m definitely nuts but nowhere near the murderer of their dreams. I go nuttier. “Tooth!” I shout. “Bagful of mirrors!” How does one say in Russian, “My wallet was just stolen and it’s red vinyl with a velcro patch and white letters stenciled on it that says in a beautiful, understated block font, WILLIE NELSON?” How do I explain that the one thing that means the most to me; that has traveled around the world with me; that is the unflinching symbol of my personal irony and thus my very strength, has been stolen?

The thief could have been any one of the punks lining the wall, but the one wearing a torn red sweater saw me seeing him and darted out of the club. And now he’s gone.

I collapse on a nearby stoop in a messy pile. Around me, broken white bits of poplar spin like gossamers of cotton candy. It’s dizzying. “Willie,” I wail, and wonder about the hour. I remember getting to the club after a three-mile walk across the city. I remember sauntering up to the bar in my jeans and sweatshirt, a boyish, mushroom-shaped dowd next to these Russian women: all some kind of blond, with legs like white pillars. Pivo, I have said at least five times this evening, the sixth, in an unsophisticated English stupor: “Beer me.”

I am here for a writing conference. Mikhail, Misha, the director, approaches. Misha is short, with a black bushy beard. He is a man who long ago mastered the art of simultaneous joy and disdain, and is usually smiling officiously. But not now. Now he’s frowning. It is obvious that I am just one of a series of problems one encounters when one chooses to direct a writers’ conference. I put on a look of contrition. Misha puts on a look of concern. “What’s this,” he says.

“It’s a penknife,” I say.

I have answered in Russian, and Misha starts laughing. He laughs big, like a sailor, and pulls me to my feet. His beard swishes my cheek. It smells like vodka and fire. I tell Misha about the torn red sweater, and he makes a call on his cellphone. Seconds later, a large white van roars to a stop in front of us. Misha sees the van, puts on a serious face and opens the door. “We’re going to the cops,” he says, and he says that word “cops” like it’s spelled “kopz,” and it’s his way of sounding like a cool hipster American, which he absolutely is.

“C’mon,” he says. “We’re gonna take a ride.”

This is a country, I will learn, that is spectacular at doing nothing.

Misha is wearing a Three Stooges t-shirt and a wool blazer with the sleeves rolled up. He teaches at an American college in upstate New York. He grew up in St. Petersburg née Leningrad, was a member of the samizdat, and then came to America where he published a brilliant book of stories. Misha will eventually go on to win several major writing prizes, leave the American college for a university in Canada, and The New Yorker will regularly publish his Facebook posts and essays on Trump’s America, on his Putin déjà vu: “A Reagan-Trump-USSR Winter Dream: how would the 1980s have played out for the Soviet Union if Donald Trump had been president then, rather than Ronald Reagan?”—but this is not what impresses me about Misha at the moment, because at this moment I am thinking about my total inability to communicate, and am impressed only with the way this small bearded man before me claps his hands and things get done.

I get into the van and as soon as the door rolls shut the driver takes off, hurtling down the streets like a driver in a cartoon. Misha and the driver talk in fast Russian and the bridges go by, there we go, over the canals and the bridges, the golden lions, moving onto narrow roads that bust open into plazas as wide as the fields I grew up in. The driver punches a button and a siren goes off like a bomb alert. Gold churches, gold railing, gold statues. Then gold goes to black and the streets are soot-covered. The architecture goes to basic; the height of the houses plummets. Houses with shutters full of missing pieces and swinging pieces that hang off their frames like broken fingers, the teenagers busting Baltika bottles, the man lying on the side of the road in a ditch—is he dead? I think he’s dead! His head is brown and his legs are white. It’s too dark to tell if it’s blood but he’s not moving. I reach for Misha to stop the van to inspect the dead man, but it’s too late, we’re already too far past him. The smell of coal consumes us.

I feel like I’m the one who’s done the stealing.

The van stops in front of a square gray building. Misha and I are immediately yelled at by two men who supposedly came out to greet us. They are wearing gray uniforms with red bands around one arm, and we’ve already somehow angered them. They are both tall and humorless, and next to them, Misha transmogrifies. He takes the same form. He actually gets taller. Drunkenly, I admire Misha’s assimilation, and try to help: “Here,” I say. “Vót moyá kníga. Vót aná.”

I have offered them a book I do not have.

Misha gives me a stern look.

I give him a hopeful look. Am I helping?

I am not helping. The men look at me square and narrow their eyes. Wearing this sweatshirt ensemble, this anti-fem garb, I am suspicious. Perhaps I am really a trickster. Perhaps I am really a man. I narrow my eyes back.

Misha laughs lightly, and quickly ushers us all into the reception area of the St. Petersburg Police Headquarters. He says he knows the Chief of Police. There are five men now, all in the same get-up as our man who greeted us outside. The five red bands are imposing, but not nearly as imposing as the stance these men take when appraising us, and our situation. They stand with their arms crossed, legs apart, as if assuming a ballet position. Behind them, the shades to the windows are pulled down all the way, blocking out the light of the night. Grains of cement from the crumbling floor spill out from cracks like the earth underneath is trying to flip on its side and roll over. There are no computers.

The red-banded men point at me, and scowl. I have, it seems, managed to inconvenience everyone. I sit down on a bench and feel useless.

Misha sits down next to me. We are both sobering up, which is a sobering thought. “No worries,” says Misha, and generously proffers what I imagine to be a few comforting lies. “There have been many, many phone calls. Everyone is looking for the man in the red sweater.”

“The torn red sweater,” I say.

“Yes,” says Misha.

To pass time, he reaches into his bag and pulls out a book. It’s an old anthology of articles from The Onion: “Why Does Marlon Brando Keep Playing Fat Characters?” and “Mothership Accidentally Descends On Hootie Concert” and “Taco Bell Launches New ‘Morning After’ Burrito” and “Casual One-Niter Gives Strom Thurmond Change Of Heart On Gay Issue.”

I’m grateful to Misha for his attempt at ironic detachment, but my heart isn’t in it. I’m busy considering the phrase “an exercise in futility” in new light. Russians, I begin to see, think about futility differently than Americans. They understand that futility actually is something to exercise.

This is a country, I will learn, that is spectacular at doing nothing.

After one lazy hour, a guard comes over, and starts gesticulating. We are, both of us, to follow him.

We’re going to meet the Chief of Police.

The St. Petersburg police station has an upstairs level of administrative offices, most of which turn out to be empty, whether from the time or the economy, I am uncertain. The floor of the hallway is made from the same cement on the first floor, but instead of crumbling from the pressure of the earth, slants entirely at a thirty-degree angle. It’s three a.m. We walk on our ankles to the tiny office where we will spend the next four hours.

I have never, in my life, seen one man work so slowly.

The guard opens the door, and inside, a man with a round head is sitting at a desk, his face as flat as slate, balding. He already looks bored. His eyelids bear two natural and uneven folds that shade his eyes in tiny visors. He gazes at us from underneath these visors, and points to the two wooden chairs that nearly block the entrance. We sit.

The Chief and Misha begin conversing quietly, Misha gesturing to me in a friendly manner; the Chief gesturing to me in an aggravated manner. I stay perched on the edge of my chair, tight as a bird, trying desperately not to smell or look drunk. Then I’m not sure it matters. The beer bottles that spill out from the Chief’s coat closet are all empty. Some stand upright, others lie on their backs in precarious lilt, and will roll down the thirty-degree angle if nudged even just slightly.

The Chief brings out a fresh sheet of paper and begins composing his Cyrillic. This is a police report: hand-written, in blue ink. He paints figures on the page with the care of a Japanese calligrapher.

I have never, in my life, seen one man work so slowly.

Misha nods deeply and reiterates, “torn red sweater,” then leans his head against the wall to snooze.

The wallpaper is covered in big pink peonies with green vines and smells like soot. In a quiet murmur, the radio, one of those knobby Sixties ones, alternates polka medleys and Christina Aguilera. I adjust my bottom. The chair creaks. The chairs have thin, precarious legs carved in a 19th century style, and quite possibly were bought or pilfered from the Mariinksy Theater where just last night Willie Nelson and I sat through a three-hour Russian comedy, the title of which was the only thing I understood: Sheep and Wolf.

In my estimation, Sheep and Wolf was about two Victorian families who feuded. The actors also passed around a paper mask with eyeholes, which seemed to play some crucial part in the humor. In the end, an old woman made everything okay.

After an hour, the Chief starts eyeballing my chair, so I decide to have a look around. When I exit the room, Misha doesn’t move. He’s nodded off completely.

Christina Aguilera squawks in de crescendo.

In the hallway, I look out a window to try and figure out if it’s morning. Here, it’s not always easy to tell the difference between skies. I pretend I’m in a movie, wistful about something. I don’t know what. I stare out the window at the rooftops of St. Petersburg until my eyes glaze over, and I become a part of the cinder-blanched landscape. Willie is out there somewhere. He is there and I am here and we are both so far from the land or the people that know us.

I glance down at a large burlap bag slouching in a corner of the hallway. It’s nearly four feet high and two feet wide, bulging at the sides. The front reads, in English, “GRANULATED SUGAR.” I look around for any sign of the red-banded men, and peek inside. It’s full of paper, torn in tidy quarters.

I look closer. I recognize the Cyrillic. I know that blue ink. These shreds of paper, all of them, are police reports.

And suddenly it all makes sense. Why Willie would go into it. Go as far in as he could. Because once lost he can lie for days on the street, empty and long-abandoned by the punk in the torn red sweater, picked up by a bum who tries to sell him for a “loosie,” an American-brand cigarette; he can be swept next to the woman sitting on the street who’s missing half an ear—she’s selling swollen, gray meat and elbowing off the gypsies—and he can be traded for a pivo at the Golden Dolls titty bar and lie on the soft carpet in full view of the shimmering, late-nite Slavic maracas; he can be kicked down the five-hundred foot escalators that lead to the subways, getting out with a small boy at the KGB park to lie on the bank and sun-bleach the color from his threads; he can be tossed into the sexy curves of the Griboyedova Canal at midnight and float like garbage under the arches, in and out of the moon’s view, until he enters the wide arm of the Neva to wait, just like everyone and everything else, for the bridges to rise like the trunks of elephants and then, with the cargo boats, pass through.

__________________________________

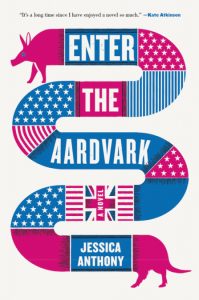

Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony is available now via Little, Brown and Company.

Jessica Anthony

Jessica Anthony is the author of three books of fiction, most recently the novel Enter the Aardvark, a finalist for the New England Book Award in Fiction. A recipient of the Creative Capital Award in Literature, Anthony wrote The Most while guarding the Mária Valéria Bridge in Štúrovo, Slovakia. She lives in Portland, Maine.