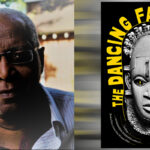

The Writer Who Rejected the Black Literary Bourgeoisie

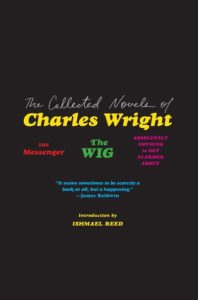

On Charles S. Wright's 1960s Novels of Societal Rejects

Since at least the 1920s, in order for a Black writer to achieve literary success they would need to find a White individual or organization to sponsor them, whether it be a wealthy Park Avenue patron, the Communist party, or, currently, bourgeois academic feminism. The uncontrollable and brilliant bell hooks said that she was told by White feminists that in order to succeed, she had to write for them.

There were Black writers who were contemporaries of James Baldwin, who wrote as well as he, but those who dictated trends in Black culture did not find their works comforting. John A. Williams and John O. Killens exposed the hypocrisy of the Greatest Generation. The slave masters in Margaret Walker’s masterpiece, Jubilee, are vicious and cruel, not merciful. Gwendolyn Brooks turned her back on the establishment that had honored her. She went Black!

In The Fire Next Time, Baldwin promises his liberal constituency that he will redeem and educate them, because they are “the chorus of Innocents” who are unaware of how their racist actions impede the progress of Black Americans. He distances himself from the Nation of Islam and reports to his backers that they might have been financed by Texas millionaires when their model for economic development was the worker cooperatives.

Ultimately, Baldwin concluded that redeeming the unredeemable was a hopeless task. One of the few places where the actor Leo Proudhammer of Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone feels comfortable in America is at a San Francisco Chinese restaurant. Baldwin’s sponsors replaced him with Eldridge Cleaver, who attacked the older writer, just as Baldwin was assigned to attack Black writers who were his contemporaries.

Baldwin said to me, “Ishmael, I don’t mind your criticisms, because you are a writer; Cleaver is not.” Members of my generation included Baldwin and others as part of the old guard, who had an apprentice/master relationship with canonized white writers. In Ralph Ellison’s case it was Ernest Hemingway and T. S. Eliot whom he cited as influences when Quincy Troupe, Steve Cannon, and I interviewed him in 1977, which was published in Al Young and my magazine, Y’Bird, vol. 1.

There’s nothing in Invisible Man that connects him to Eliot. For Baldwin it was Henry James, clause by clause. So enamored of James was Baldwin that he wrote Jamesian criticism and was honored when receiving a portrait of James from the writer’s son.

While many of the metaphors in Baldwin’s works—which I once stupidly called “Jewish books”—were based upon the Old Testament, some of the members of my generation of writers studied Islam, and African languages, after Malcolm X influenced them. I based some of my work on Haitian religion, which had been previously explored by Zora Neale Hurston and Katherine Dunham.

We were eager to strike out into new aesthetic territory. We found a trailblazer in Charles Wright, who was introduced to us by James Baldwin. Here was a writer who spun a tale based upon a character’s attribute, as he did with Lester Jefferson’s hair. The two wrote in different styles. What they have in common is that, as bisexuals, they might view reality from a different perspective than those who are of one or another persuasion, sexually. Their basic difference is that Baldwin, in the words of Chester Himes, was “ambitious,” while every time Success knocked on Wright’s door, he wasn’t home.

Hair is such an issue in Black culture that in 1992, the late sociologist Kennell Jackson, a professor at Stanford, taught a seminar called Black Hair as Culture and History. The Wall Street Journal published a column about the course that was written by David Sacks, then editor of the conservative student-run newspaper, Stanford Review. Kennell replied in a column so brilliant that he sat his conservative critics down.

While Whites can wear any style of hair they desire, Black hairstyles like the Afro have been controversial. A Black newscaster was fired for wearing cornrows. Charles Wright exploits the politics of hair in The Wig, which allows him to create a fantasy about a magical wig.

Charles Wright’s memoir, The Messenger, had gotten an endorsement from James Baldwin. Both were bisexual, but except for Rufus in Baldwin’s Another Country and Giovanni in Giovanni’s Room, Baldwin’s readers were not ready for the taboo-breaking cast of characters found in Wright’s The Messenger and The Wig. Baldwin’s readers would have found them repellant. They’re either drinking liquor, smoking pot, or occasionally shooting up.

All day I had been drinking: wine, beer, gin, scotch, champagne. I ticked them off in my mind, maybe to prove to myself I was still sober. I had taken six bennies to ward off a high and smoked a little pot.

Turning tricks has a literal meaning in The Messenger and The Wig but also reflected the miserable characters who, in Wright’s words, resided in the “outhouse” of the 1960s Great Society: hustlers, prostitutes, junkies, and those whose sexual identities were ambiguous.

Tricks defined the lives of these characters. They spent a lot of time tricking themselves, imagining that they were their favorite movie stars. Miss Sandra Hanover of The Wig channeled Ava Gardner, Bette Davis, and Gloria Swanson, and has a Lena Horne smile. Lester Jefferson has a “Bogart smile.”

While some played the Murphy game of luring an innocent man with a promise of sex, only to make off with the john’s money—these characters did a Murphy on themselves. Unable to achieve the real thing, they lived vicariously in the lives of celebrities.

Unlike Baldwin, who ruthlessly took down the competition—Chester Himes, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, etc.— Charles Wright had nothing to do with the cutthroat Manhattan token wars in which the sons slay their fathers and the daughters slay their mothers. Richard Wright’s classic, Native Son, was subjected to a literary drubbing in the Partisan Review, the literary power broker at the time. It might have had something to do with the problems the publisher, William Phillips, had with Wright. In his memoirs, Phillips complained about Wright’s anti-Americanism. Encountering him in Paris, Phillips wrote, “Unlike his books, Wright was sweet and gentle. But he lived in his own limbo, for he was in his anti-American phase, therefore not part of the American contingent, nor could he be French.” This is an odd remark.

Not only did Richard Wright move in a circle that included Black expats like the cartoonist Ollie Harrington, Chester Himes, and others, among his French friends were Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre. Gertrude Stein called him a “genius.” Near death, Baldwin confessed to Richard Wright’s daughter Julia that he had been used. Scholars write papers about Baldwin’s attack on Richard Wright without understanding the politics behind it. Richard Wright wasn’t the only father taken to task by Baldwin.

Every attempt to take Charles Wright “uptown,” the image of cultural success, was rebuffed by the author.Langston Hughes was hit by Baldwin in the New York Times, March 29th, 1959. He wrote, “I am amazed all over again by his genuine gifts and depressed that he has done so little with them.” Both Richard Wright and Hughes were his patrons, and in Richard Wright’s case his benefactor. About Chester Himes’s The Lonely Crusade, he wrote “[He uses] what is probably the most uninteresting and awkward prose I have read in recent years,” adding that Himes “seems capable of some of the worst writing this side of the Atlantic.”

Charles Wright refused to audition as a hatchet man contestant in the Manhattan token wars in which only one Black writer is left standing during a given era. When I asked George Schuyler, author of the classic novel Black No More, why he, at the time, hadn’t received more recognition, he said he wasn’t a member of The Clique. Tokenism deprives readers of access to a variety of Black writers and smothers the efforts of individual geniuses like Elizabeth Nunez, J. J. Phillips, Charles Wright, and William Demby, whose final novel, King Comus, I published.

In the 1960s, when literary-minded editors influenced publishing, such a rejection by a master would have been thought unthinkable. A woman acquaintance advised Charles Wright to be more sociable. You know, network. Every attempt to take him “uptown,” the image of cultural success, was rebuffed by the author. His bad manners sent an interviewer from a prominent women’s magazine scurrying after he decided to urinate in public. He despised the elite and their mannerisms. He called members of the Black middle class “cocksuckers.” He found both the Black and White “silent majorities” contemptible. Ridiculed their pretensions. He judged Black political leaders to be charlatans.

His community was that of the outcasts, the rejected, the freaks, who would eventually make it into the mainstream. Some of his characters would now be referred to as sex workers. Restrooms, in some places, are now all-gender, and those outlandish characters in Wright’s novels and nonfiction, though not given credit, led to these reforms. They fought the vice squads at Stonewall and in San Francisco.

I am on the stoop these spring nights. The whoring, thieving gypsies, my next door neighbors, are out also. Their clientele is exclusively male. Mama, with her ochrelined face, gold earrings, hip-swinging beaded money pouch, flowing silk skirts, is sitting on her throne, the top step. She went to jail the other day, made the Daily News. She had clipped a detective and tried to bribe him with ten bucks.

On the day that The Wig was reviewed in the New York Times, favorably, instead of showing up at some uptown posh literary soiree to cash in on his fame, he was found in one of those crummy hotels he inhabited frequently. Hotels at risk of being condemned or even demolished. Instead of using his support from gallows humor theorist Conrad Knickerbocker to hobnob with literary celebrities he sought to ease his pain by getting high. Among the denizens who frequent Wright’s fiction, liquor is referred to as “joy juice.” Self-medication.

Baldwin’s character John in Go Tell It on the Mountain dreams of eating good food and wearing expensive clothes.

The way of the cross had given him a belly filled with wind and had bent his mother’s back; they had never worn fine clothes, but here, where the buildings contested God’s power and where the men and women did not fear God, here he might eat and drink to his heart’s content and clothe his body with wondrous fabrics, rich to the eye and pleasing to the touch.

Charles Wright was still washing dishes and cleaning toilets after writing two classics.

Baldwin was a hip, sophisticated New Yorker; Wright never really overcame his Midwest innocence. Kansas City, St. Louis, he even visited Albuquerque where he might have left a Mexican woman with a child. Sometimes, he appears to be a Midwestern kid lost in the big city. Like other minority writers he writes about the indignities experienced by those whose color makes them a target of racism, but he does it with an originality. With humor. Dealing with racial profiling, he includes an anecdote about the police making him run for their amusement after he boasts he’s a good runner.

Wright chooses a comic surrealism (among the painters he cites is Salvador Dali) to point out the experience of a shit-colored Black man in the United States. While writers like Baldwin and the underrated Louise Meriwether might condemn the absentee landlords who abandon their tenants to the lack of heat, bad plumbing, cockroaches, and rats, Himes and Wright use these conditions to spin some tall tales. Himes’s rat has created an apartment within a box that includes the rat’s provisions, such as condoms. The rat reads comics. Wright’s lead rat is named Rasputin.

After Baldwin’s classic Go Tell It on the Mountain was published, the marketers must have told him that in order to cross over, he would have to give some White characters a major role in his novels. And so while heterosexual relationships are the pits in Another Country, it ends with the White bisexual, a person of means, Eric, awaiting his lover’s arrival from Paris.

In Giovanni’s Room, another well-off White American male, David, journeys through the novel trying to choose between heterosexual and gay relationships; he decides that he is gay after having cast aside lovers both heterosexual and gay. Vivaldo Moore of Another Country exercises his White man’s burden by trying to rescue Lena from Rufus and Rufus from himself.

Wright liked jazz. Wright was Charlie Mingus. Wild. Expressionistic.The White, Black, and Asian men in Wright’s books are too busy trying to get high to engage in such square tasks. Their expressions of their sexual inclinations are out front. They are not sexual Hamlets. Their communities are fleeting. There are no long-lasting commitments. Wright shares a woman named Shirley with a doctor. He has a platonic long-distance relationship with a woman named Maggie. If he loved anybody, it was his grandmother.

Characters who are not even introduced to each other assemble in apartments for sex and to do drugs. While novelists of the 1950s Manhattan Testosterone School saw women as things that you could fuck, for bisexual writers like Wright and Baldwin, women were works of art. Both Wright and Baldwin were obsessed with the style of women. How they are made up. What they are wearing.

I opened the door and Mrs. Lee came toward me puffing, her short, plump body cleverly concealed in a black suit. She was weighed down with garlands of oriental pearls, a large garnet-pearl brooch, and exactly eleven gold bangle bracelets. A sable scarf dropped seven skins carelessly from her shoulders; a garnet velvet skullcap was perched on her thin, red-gold hair, fluffed wild. Her hair was not unlike that of Tike and Pike, her two miniature French poodles. She had the face of a warmhearted cherub.

As a pretty yellow boy, shown on the original cover of The Messenger, Charles had plenty of opportunities with both men and women. His cousin Ruby’s moral instruction to the 14-year-old Charles included a warning.

Your father is a louse. I know Grandma hasn’t told you anything. But she could, believe me. You’re a goodlooking kid. Women are going to be after you. White, black, all kinds. They’re going to be dying to get into your pants. But if you take the advice of an old fool, you’ll play it cool. When you get into the prime of your life, you’ll be a played-out tomcat. I’ve spent 35 years discovering how rotten life is if you waste it on nothing. Never be bitter, Sonny. Only people who can’t face life and hate themselves are bitter. Maybe I was born black and lost my voice to teach me a lesson. Well, kid, I learned. I know damn well I learned something being born black that I could have never learned being born white.

Critics use the term “jazz” loosely when referring to poetry and fiction. A case can be made for its existence in The Wig. The tempo and wealth of allusions fly by so fast that one has to reread some of the sections as one would go over the notation of, say, Bud Powell’s piano solo for “Tempus Fugit.”

Everyone seemed to jet toward the goal of The Great Society, while I remained in the outhouse, penniless, without “connections.” Pretty girls, credit cards, charge accounts, Hart Schaffner & Marx suits, fine shoes, Dobbs hats, XK-E Jaguars, and more pretty girls cluttered my butterscotch-colored dreams. Lord—I’d work like a slave, but how to acquire an acquisitional gimmick? Mercy—something had to fall from the tree of fortune! Tom-toms were signaling to my frustrated brain; the message: I had to make it.

Baldwin sought solace in the blues and spirituals in his work. Wright liked jazz. Wright was Charlie Mingus. Wild. Expressionistic. And though the form of a dialogue between him and his straight man reminds me of Langston Hughes’s “Simple” series and desires to be the literary son of Ernest Hemingway, author of the poem, “Nigger Rich,” his syntax leans more toward that of the Beat master, Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Besides, surrealism is a hard sell to publishers who believe that Black art should be pedestrian. Imitative of The Masters. But Wright’s surreality is closer to the reality that most Blacks have experienced since their arrival here. Every day you might encounter a surreal situation. Like my being racially profiled while relaxing in a famous landmark cemetery. In a nod toward the Neo-Slave Narrative novels of today, a term I created in 1984 to describe my novel Flight to Canada, a slave shows up in The Wig.

“What are you doing over here?” I said severely. “Don’t you know beggars aren’t allowed over here?”

“I ain’t no beggar,” the man said. “I’m a runaway slave.”

“Don’t give me that shit. You half-assed con man. Slavery was outlawed years ago. Centuries ago.”

Uptown falsely claims that the New Journalism begins with Tom Wolfe. No, it began downtown when poets and novelists like Charles Wright began writing journalism for The East Village Other and The Village Voice, where some of the material in Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About appeared.

The Village Voice had the good sense to hire Wright. In Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About he continues depicting the downtrodden, the winos, the prostitutes, the queens found in The Wig and The Messenger. The high points are the pieces that read like travelogues. Chinatown, the Catskills, the Bowery. His essay on welfare is written by someone who received checks from the program and though stereotyped as a Black program, most of the beneficiaries, like those of the Great Society programs, are White.

While his friend James Baldwin had apartments in Turkey, New York, and a home in the South of France, Wright lived in the Salvation Army hotel on the Bowery, where now you have to pay as much per night for a room in an Art Deco hotel as you would at the Waldorf.

As a yellow Black man who was both despised and rewarded because of his skin color he reminds me of Chester Himes, another yellow Black man. His cynical take on the rising Black militancy reminds one of Himes’s satire of the civil rights movement in Pink Toes. Baldwin, however, embraced the new militancy in the guise of the character Black Christopher in Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, the novel that lost him the support of The Family, the name given to the Manhattan liberal literary elite that has been imposing tokens on the Black literary scene for 100 years, because he satirized his former patrons mercilessly.

The Family struck back with a Times hatchet job on the book written by Mario Puzo, possibly because Baldwin’s Italians were more complex than his. But Baldwin and Himes could vacation from the United States and be wined and dined by the Europeans and, in Baldwin’s case, the Turkish elite. Among the circle that Himes moved in was Pablo Picasso. I asked him if Picasso had offered him a painting. He had. Himes rejected it because he thought it was absurd.

Charles Wright remained in the United States and took his licks, psychologically, spiritually, and physically. The character Fishback, the necrophiliac, says of the United States that it is filled with “nasty images.” They’re rounded up in Wright’s work. The memorable phrase from both my and Wright’s mentor, Langston Hughes, can apply to Wright’s work. “Laughing to keep from crying.”

While his friend James Baldwin had apartments in Turkey, New York, and a home in the South of France, Wright lived in the Salvation Army hotel on the Bowery.When I read passages from The Wig cited in the Knickerbocker review, I figured that a writer had arrived who would break Black writers out of the aesthetic prison that critics had placed around them. A Faulknerian quagmire of cluttered baroque prose. Copycat Black Modernism. If young novelists have extended his experiments, Whitehead, Beatty and LaValle, it was Wright who began the jailbreak.

After reading the review, I called my friend, poet Steve Cannon, now a gallery owner and magazine publisher, who was subjected to a lengthy profile in the New York Times magazine, and told him that this might be the guy.

We sought him out. He was living at the Albert Hotel. As we approached his room, we found him engaged in a tussle with another guest. His life was a tussle. From the time of his childhood when he was taunted by his schoolmates for being yellow, he was an outsider who found companionship with other outsiders.

The final stages of Charles Wright’s career weren’t as dire as the New York Times described in their obituary. Ironically, it was a grant to Mercury House from the National Endowment for the Arts that was responsible for his comeback, the same National Endowment that denied him an individual artist grant when he really needed the money. I have photos of Charles Wright taken at a dinner in his honor at a downtown restaurant. He didn’t seem to me that he had “vanished” in “despair.” Others were taken at a book party held at Steve Cannon’s Tribes Gallery.

One day, Richard Pryor came to my home in the Berkeley Hills with a package of writings that he wanted me to publish. His standup routine included the kind of rogues and outcasts that Wright had included in his writings. Pryor wanted to get the approval of my friends and me. We’d warned him that he couldn’t bring his corny Las Vegas routine to Berkeley. We viewed ourselves as members of the cutting edge. Our approch was a brutal, ironic, satirical takedown of American society’s hypocrisies delivered in a combative and comic style.

For those who patrol Black letters like their antecedents who controlled the movement of slaves, we went too far, then as now. In his autobiography, Pryor says that I turned him down. Not true. I jumped at the chance to publish him. He was the one who withdrew his work. Little did Richard know that Charles Wright had already written the fiction that Richard wanted to write.

__________________________________

The Collected Novels of Charles Wright. Copyright © 1963, 1966, 1972, 1993, 2019 by Charles Wright. Introduction © 2019 Ishmael Reed. Reprinted here with permission of Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.