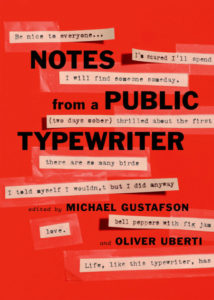

The World's Smallest Publishing House: A Typewriter in a Bookstore

Michael Gustafson on Opening Literati Bookstore

In the spring of 2013, my wife, Hilary, and I opened Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Opening a community-minded independent bookstore was a dream we’d shared since we bonded over books on our first date. After we got engaged, we quit our jobs in New York City, moved home to Michigan, took out a loan, and signed a lease. We were in our late twenties, pursuing a dream. We were terrified.

When opening day arrived, we unlocked the door and held our breath. One by one, people walked inside, paged through new books, discussed favorite authors. The wood floors creaked; cash registers rang. The bookstore came alive. As I stood at the register, my ears perked up. Amid the din, I heard the faint but distinct cadence of someone typing.

That morning, I had set out a typewriter on our lower level for anyone to use. It was a community-building experiment: What if people could walk into a bookstore and type anything they wanted?

Would they write haikus, confessions, or declarations of love?

Would they contemplate the meaning of life? Would they make fart jokes? Would people even know how to use a typewriter?

The public typewriter experiment, for me, was also personal. The first typewriter I ever fell in love with was my grandfather’s—a 1930s Smith Corona. Because he died when I was young, my memory of him is limited to impressions: visits to the Florida condo he shared with my grandmother, beach picnics, golf cart rides around the neighborhood, and an alluring black typewriter on his writing desk. One year, long after he died, Grandma gave me his Smith Corona for Christmas. At the time, I was a struggling writer. Seeing his old typewriter again stirred something in me. As I hunched over the keys, I imagined my grandfather also click–clacking away, equally hunched, considering each word. His typewriter made writing fun again. And for the first time since his death, I felt connected to him, to a past I never really knew. Now, his typewriter is rarely far from sight; I keep it inside a glass display case below our bookstore’s register.

“Our community of note-typers has shown that impactful writing isn’t limited to bestselling authors. Each of us has a note to leave behind, and I realized more of them deserve to be read.”

The typewriter I set out on opening day was a light blue Olivetti Lettera 32. I inserted a clean piece of paper and let it be. There were no prompts. No directions. Just the world’s smallest publishing house, waiting for an author. One of the notes I found that first day was: Thank you for being here. I didn’t see the typer’s identity, so it appeared as though the typewriter itself was thanking me. As though the dusty machine was happy to be used again.

Soon, more notes accumulated. People proposed, broke up, confessed, apologized, joked, and philosophized. I had to buy more paper, more ink ribbons, more typewriters. Typewriting had become part of our bookstore’s identity. I taped favorite notes to a wall behind the typewriter. I shared some notes in store newsletters and on social media. And in 2015, we commissioned artist Oliver Uberti to paint 15 of them along a 60-foot stretch of our building. It’s now one of the most photographed locations in town.

Customers, friends, and family began encouraging me to turn these notes into a book. At first, I was apprehensive. But then I read through the piles of messy, typewritten pages again with Oliver. Some made us tear up; many made us laugh out loud. Our community of note-typers has shown that impactful writing isn’t limited to bestselling authors. Each of us has a note to leave behind, and I realized more of them deserve to be read. They shouldn’t be locked inside my filing cabinet at home. Inside our store, surrounded by books that have been labored over by authors, editors, and marketers, there’s a way for people to publish directly into the world in permanent ink—spelling errors and all.

Some nights after we close, when the bookstore is quiet and the lights are dim, I’ll pull from the display case my grandfather’s old Smith Corona. I’ll set it on a table in the dark, where it makes a loud thunk. The ink still smacks one letter at a time, as it did 80 years ago.

I pause in the quietude. I wonder, like so many others have before: What should I write? I decide to write to the person who gave me the typewriter. The click–clack reverberates. I strike the wrong letter. My pinkie reaches for the delete key, but there isn’t one. I’m glad. I keep typing.

Dear Grandpma,

![]()

City of Books

While on the Ann Arbor District Library’s website, I came upon a collection of historic photographs of the city. One image, in particular, caught my eye: State Street, in 1955, from the roof of the old Wagner’s clothing store, a few doors down from the State Theater. The University of Michigan campus hides just out of frame. Among the historic buildings, I saw neon signs and hand-painted awnings, Oldsmobiles and fedora hats. Zooming in, I found three signs that read books and a typewriter shop. A book lover’s paradise.

I printed this photo and taped it on my wall.

Ann Arbor has a rich bookselling past. Sixteen years after this photo was taken, the original Borders bookstore opened around the corner in 1971. According to the Ann Arbor News, Tom and Louis Borders “received advice not to open a bookstore in Ann Arbor since at that time one store had closed and several others were on the verge of it.”

Before we opened Literati in 2013, Hilary and I received the same advice. Borders had just sold its last book in 2011, and before that, Shaman Drum, another beloved independent bookstore, closed in 2009. Some close to us said we were crazy. Some called it professional suicide. “How can you survive if Borders couldn’t?” a landlord asked. He rejected our lease bid and hung up the telephone.

“When a bookstore closes, it does not die and disappear. A bookstore reincarnates.”

It was a tough time for bookstores nationwide, and the struggle was well documented. CNN profiled Borders’ last days with an article titled “The death and life of a great American bookstore.” I remember reading this same article while living in Brooklyn with Hilary. We both grew up in Michigan. Hilary browsed the Ann Arbor Borders’ bookshelves as a kid. I remember feeling both sorrowful and motivated and thinking how a well-read university town like Ann Arbor needed a vibrant, downtown independent bookstore.

A few months later, newly engaged, we began working on a business plan.

When we moved back to Michigan, we were told that at one point Ann Arbor had the most bookstores per capita of any US city. The city still supports ten indies, but there are fewer now than 30 years ago. Before we opened, people told us they were afraid bookstores would disappear forever, perhaps the same thing the Borders brothers were told decades earlier: “I thought Ann Arbor would never get another bookstore!” or “I’m so happy a bookstore is actually opening.”

Literati Bookstore exists because great bookstores existed before us. Our inventory sits on shelves repurposed from that same original Borders store where Hilary once browsed. Two booksellers profiled in CNN’s eulogy are now Literati booksellers. And in 2015, we were featured in a new article, “The Return of the Great American Indie Bookstore.” A flattering statement, but it made me wonder: If bookstores return, where do they return from?

When a bookstore closes, it does not die and disappear. A bookstore reincarnates. The ideas contained in the bookstores from that old 1955 Ann Arbor photograph—Slater’s, Follett’s, Wahr’s— have reemerged in new locations with new names. Not just in Ann Arbor, but across the country wherever entrepreneurs are inspired by bookstores of the past. Like a dormant perennial, a bookstore will sprout again.

One day (far in the future, I hope), Literati’s season, too, will end. While it exists, each week, I climb to the top of the parking garage across the street from our bookstore and photograph a bookstore in bloom. Then I turn these photos into postcards and post them on social media. I hope that, 40 years from now, a potential bookstore proprietor will not be deterred by articles, churlish landlords, and pundits predicting “the end of books.”

Instead, I hope that person stumbles upon old photographs of Ann Arbor. I hope she sees a busy downtown street. I hope she squints and sees hand lettering that reads bookstore. I hope she sees books and typewriters in the windows—a warm, inviting display—and an open door that leads to hand-painted floors and handwritten recommendations, to all that ink printed on those thousands of pages, a room of ideas waiting to be rediscovered, all over again.

__________________________________

From Notes from a Public Typewriter. Used with permission of Grand Central Publishing. Copyright © 2018 by Michael Gustafson and Oliver Uberti.

Michael Gustafson

Michael Gustafson is the co-owner of Literati Bookstore, an independent bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He is the author of Notes of a Public Typewriter. He lives in Ann Arbor with his wife and Literati Bookstore co-owner, Hilary.