The world’s oldest surviving letter by an actual Christian contains a request for fish sauce.

Sometimes the greatest secrets are right under our noses, in shuttered backrooms or buried beneath layers of decades-old junk.

One researcher at the University of Basel, in Switzerland, has discovered a treasure likely to appeal to epistolary and classical fanatics alike. Sabine Huebner, a professor of ancient history who specializes in ancient Roman social life, has researched and dated what is believed to be the world’s oldest surviving letter written by a Christian.

The papyrus letter, which Huebner dates to 230 AD, came from the village of Theadelphia in central Egypt, just southwest of Cairo, and was written in Ancient Greek by a man named Arrianus to his brother, Paulus. The translation, courtesy of Professor Huebner, is below:

Greetings, my lord, my incomparable brother Paulus.

I, Arrianus, salute you, praying that all is as well as possible in your life. [Since] Menibios was going to you, I thought it necessary to salute you as well as our lord father. Now, I remind you about the gymnasiarchy, so that we are not troubled here. For Heracleides would be unable to take care of it: he has been named to the city council. Find thus an opportunity that you buy the two [–] arouras.

But send me the fish liver sauce too, whichever you think is good. Our lady mother is well and salutes you as well as your wives and sweetest children and our brothers and all our people. Salute our brothers [-]genes and Xydes. All our people salute you.

I pray that you fare well in the Lord.

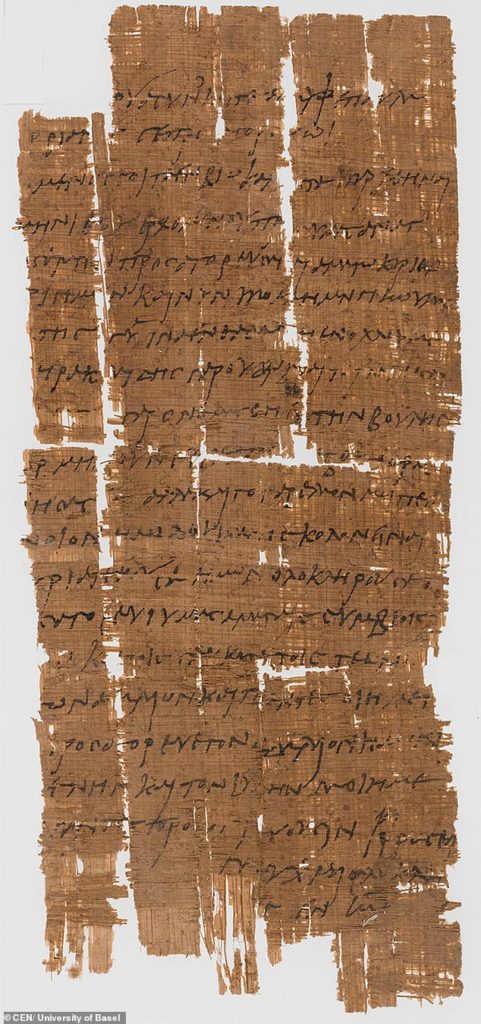

The papyrus P.Bas. 2.43 has been in the possession of the University of Basel for over 100 years. The letter has been dated to the 230s AD and is thus older than all previously known Christian documentary evidence from Roman Egypt. (Photo/detail: University of Basel)

The papyrus P.Bas. 2.43 has been in the possession of the University of Basel for over 100 years. The letter has been dated to the 230s AD and is thus older than all previously known Christian documentary evidence from Roman Egypt. (Photo/detail: University of Basel)

The use of the nomen sacrum (“in the Lord”) in the letter’s closing, a formula that commonly appears in New Testament manuscripts, was one of the most apparent confirmations of the author’s religious affiliation. That, and the fact that the author’s brother was clearly named after Paul the Apostle, a rare phenomenon at the time. “This is the oldest Christian autograph,” Huebner said, “the oldest original handwriting of a Christian that we have from the entire ancient world.”

The letter’s existence suggests that Christians during the Roman Empire weren’t universally persecuted and, in fact, some Christians from political and landowning elite families enjoyed relative peace. The majority of early Christians were Jewish-born converts, and the religion’s popularity was cemented during its rise in the first and second centuries. Followers were largely persecuted for their refusal to accept pagan worship practices, and Christianity wouldn’t be legalized in the Empire until he fourth century, under the reign of Constantine the Great.

The University of Basel had actually owned the document for more than a century as part of its papyrus collection, consisting of 65 papers in 5 languages, which it purchased in 1900 to help teach classical studies. The letter forms the centerpiece of a new book by Huebner on how papyri from Greco-Roman Egypt help reveal the social, political and economic lives of the earliest Christians.

That book, Papyri and the Social World of the New Testament, is out this month from Cambridge University Press.