The Women Who Pioneered Bicycling as a Feminist Sport

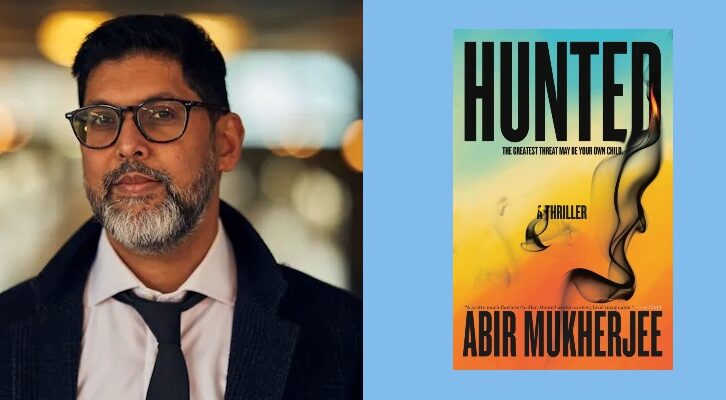

Maxine Friedman on Maria E. Ward, the Author of Bicycling for Ladies

A bright, sunny morning, fresh and cool; good roads and a dry atmosphere; a beautiful country before you, all your own to see and enjoy; a properly adjusted wheel awaiting you,—what more delightful than to mount and speed away, the whirr of the wheels, the soft grit of the tire, an occasional chain-clank the only sounds added to the chorus of the morning, as, the pace attained, the road stretches away before you!

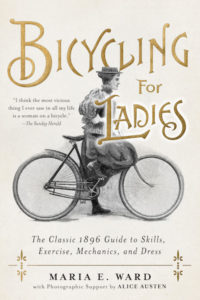

So wrote Maria E. Ward in the first chapter of her book Bicycling for Ladies, published in 1896. The Staten Island native, known to her friends and family as Violet, was a vocal proponent of bicycling as an ideal outdoor sport for women, and her book came on the market precisely at the peak of bicycling’s greatest popularity in the United States.

Teaching women how to ride a bicycle might seem an unusual topic to today’s readers, but bicycling as a widely popular and affordable activity was barely ten years old in 1896. Early versions of the bicycle included the heavy “boneshaker” of the 1860s and the high wheelers of the 1870s and 1880s, but none of the early versions found mass acceptance, and most of those who did use them were men.

Bicycling changed dramatically in 1887 with the introduction of the “safety” bicycle to the United States. Featuring two wheels of equal size, and a chain drive that made riding more efficient, the new bicycle found quick acceptance among both men and women. The addition of pneumatic tires in 1889 gave a smoother ride, and assembly-line production lowered the cost. By the early 1890s, a bicycling craze was sweeping the nation, with millions of Americans enjoying the sport of “wheeling,” as it was sometimes called.

While cycling was enjoyed by both men and women, it was women in particular who benefitted from this new activity. For the first time, it was considered socially acceptable for women to travel alone. Susan B. Anthony, a leader of the American women’s movement, stated in an 1896 New York World interview that bicycling “has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance.” Women reveled in this newfound freedom, joining bicycling clubs and participating in extended rides and country tours.

The popular acceptance of bicycling also had a dramatic and lasting impact on women’s clothing. A dress-reform movement in the latter part of the 1800s sought to make women’s clothing more practical and comfortable, and move away from the heavy and restrictive styles that impeded their ability to move freely. However, it was not until women took up bicycling that styles truly began to change. Riding a bicycle while wearing a tight-fitting corset and a long skirt was not only difficult but potentially dangerous, as the skirt’s fabric could become entangled in the bicycle. Clothing manufacturers soon designed new bicycling outfits that offered such comforts as divided skirts, shorter skirt lengths, and lighter and less confining undergarments. The corset was on its way out, and clothing that allowed freedom of movement had come to stay.

Violet and her good friend Alice Austen, the noted photographer, took full advantage of the era’s new sporting opportunities for women. They were avid tennis players as well as bicyclists, and numerous Austen photographs from the 1880s and 1890s captured scenes of both activities. Violet belonged to the St. Nicholas Skating Club in Manhattan, and was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Physical Education. She also participated in the new enthusiasm for golf, with memberships in the Harbour Hills Golf Club of New Brighton and the Richmond County Country Club. In fact, correspondence and design drawings in the Historical Society’s Ward family archival collection document Violet’s efforts to patent a variation on a golf club.

Most important, women’s bicycling outfits “should have no constricting, no tight bands anywhere, but should permit of absolute freedom of movement.”But more than any other sport, it was bicycling that captured Violet’s imagination. In 1895 she signed an agreement with the publishing firm Brentano’s to publish Bicycling for Ladies. The agreement stated that Violet would receive 10 percent of the retail price for every copy sold in the United States, and 5 percent of the net price received for copies sold in Great Britain and other countries.

Violet’s interest in the subject was all-encompassing. She described the bicycle as “an educational factor… creating the desire for progress, the preference for what is better, the striving for the best, broadening the intelligence and intensifying love of home and country.” She praised the social benefits of bicycling, but was equally interested in human physiology and in the mechanical operation of the bicycle.

Chapter headings included “What the Bicycle Does, “The Art of Wheeling on a Bicycle,” “Position and Power,” “Mechanics of Bicycling,” and “Exercise.” In the chapters “Women and Tools” and “Tools and How to Use Them,” Violet made clear her belief that women were perfectly capable of maintaining and repairing their own bicycles: “I hold that any woman who is able to use a needle or scissors can use other tools equally well.” She also addressed those who still believed that physical activities were not appropriate for women: “There is much prejudice against athletic exercise for women and girls, many believing that nothing of the kind can be done without over-doing,” and continued on to explain that success was readily achievable with proper training and practice. Every chapter of the book gave evidence of Violet’s unwavering conviction that women could, and should, lead physically active lives.

Violet clearly agreed with the new sensibility in women’s clothing, and she devoted a full chapter of her book to describing what she considered to be the ideal bicycling outfit. “The combination of knickerbockers, shirt-waist, and stockings forms the essential part of a cycling costume,” she wrote, along with shoes, gaiters, sweater, coat, hat, gloves, and an optional skirt. She went on to describe in detail the fabric, style, fit, and construction of each garment, with suggestions for accommodating the changing seasons. Most important, women’s bicycling outfits “should have no constricting, no tight bands anywhere, but should permit of absolute freedom of movement. Bicycling requires the same freedom of movement that swimming does, and the dress must not hamper or hinder.”

“Bicycling for Ladies, by Maria E. Ward, profusely illustrated, is an altogether reliable and very pretty book, specially suitable for a young man to offer a girl who ‘goes a-wheeling’ with him.”To create the illustrations for her book, Violet teamed up with Alice Austen and their friend Daisy Elliott, a professional gymnast. Using draped fabric as a backdrop, Alice took a series of photographs as Daisy demonstrated the proper way for a woman to mount, pedal, and dismount a bicycle, as well as how to make repairs. The photos were then turned into hand-drawn illustrations for inclusion in the book, as the recent technological innovations that allowed for photographic reproductions in printing were not yet in widespread use.

The book received considerable notice upon publication. Reviews appeared in contemporary issues of Book News, The Critic, The Book Buyer, and The Literary News, among others. The reviewer in Book News: A Monthly Survey of General Literature commented that the book “is a serious and dignified discussion of the advantages of wheeling with hints as to its value, its proper enjoyment, the difficulties of beginning, the dress of the rider and the care of the wheel, with remarks upon exercise, training, etc.” A reviewer in The Publishers’ Weekly: American Book-Trade Journal took a lighter view, noting that “Bicycling for Ladies, by Maria E. Ward, profusely illustrated, is an altogether reliable and very pretty book, specially suitable for a young man to offer a girl who ‘goes a-wheeling’ with him.”

Apparently pleased with the positive reception for her Bicycling for Ladies, Violet began to explore the possibility of another publication on the topic. In June 1896 she sent letters to a number of bicycle and tire manufacturers, explaining that she intended to “publish a work on component parts of bicycles, and chiefly on bicycle tires.” She requested descriptions of each company’s particular tire, and also solicited paid advertising from these manufacturers to offset the expense of the new publication. The advertising manager of the Pope Manufacturing Company, a major bicycle manufacturing firm, responded that they had received a copy of her book, and having “noted with much interest your clever work within,” they would be “glad to have particulars of the larger work on this subject that you have in preparation.” Other manufacturers, unfortunately, declined her invitation, and the second book was not published.

Violet Ward and Alice Austen shared their enthusiasm for bicycling with fellow Staten Islanders. Their names appear as the only two members of the Staten Island Bicycle Club’s Executive Committee on a flyer dated June 1, 1895. The flyer notified potential members that after one successful season, the club had secured quarters in a building at the corner of Jay Street (now part of Richmond Terrace) and Wall Street in St. George. The clubhouse featured assembly rooms, locker rooms, a “wheelery” for bicycle rentals and repairs, and a storage room where “competent men will be in charge,” should anyone wish to keep their bicycle in the building.

Along with serving on the club’s Executive Committee, Violet Ward also took on the task of managing the new wheelery, named the Staten Island Bicycle Shop. In June 1895 she sent a letter to the Unadilla Tire Company, explaining that she was opening a bicycle store at St. George and would like to receive their catalog and wholesale price list. The Staten Island Historical Society’s archives contains several invoices that show the equipment she purchased in September and October 1895 for the shop, including plugs, bolts, cement, springs, varnish, and pedals. An invoice from December 1895 records payment from a Mrs. Harding for repairing a puncture at a cost of one dollar.

At the time the Staten Island Bicycle Shop came into being, only five other bicycle businesses were listed in the Staten Island business directory. In 1898, the list of businesses under the heading of “Bicycles &c.” was up to fifteen. It is not known how long the Staten Island Bicycle Shop remained open, but it does not appear to have been a long-lived operation.

By the early 1900s, on Staten Island and across the country, the vast enthusiasm for bicycling had waned. There are differing theories about why the bicycle craze passed, but many people credit the arrival of the automobile with bringing an end to the bicycle’s heyday. In 1911, only six bicycle shops were listed in the Staten Island business directory, as compared with eighteen automobile dealers and repair shops. But Violet Ward and Alice Austen would no doubt be pleased to know that today bicycling is once again riding a wave of popularity, and that they were among the pioneers who helped pave the way.

__________________________________

From Bicycling for Ladies: The Classic 1896 Guide to Skills, Exercise, Mechanics, and Dress by Maria E. Ward, with a foreword by Maxine Freidman. Used with the permission of Apollo Publishers.