The Wind in the Willows Isn’t Really a Children’s Book

Nor, Mysteriously, Does it Contain Any Willows . . .

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most famous English children’s books, one of the most famous books about animals, and a classic book about “messing about in boats.”

Famous, it certainly is. Although it has never been quite the international icon that Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has become, Kenneth Grahame’s eccentric masterpiece can be read in Afrikaans as Die Wind in die Wilgers, in Italian as Il Vento nei Salici, in Finnish as Kaislikossa suhisee, in Portuguese as As Aventuras de Senhor Sapo and in dozens of other languages. It is currently available in well over 50 editions in English: there are versions in verse, graded readers for learning English as a foreign language, audio and video adaptations, plays (notably by A.A. Milne and Alan Bennett), films, picture books (with or without stickers), pop-up books, knitting patterns, graphic novels and scholarly annotated editions. There are sequels, such as William Horwood’s The Willows in Winter (1993), gospel meditations, a cookery book and Robert de Board’s Counselling for Toads (1998), an introduction to psychotherapy. E.H. Shepard’s illustrations have been used on national postage stamps and to advertise England itself in the 1980s English Tourist Board series, “Making a Break for the Real England.” The book has been the inspiration for a sculpture trail, one of the most successful rides in Disneyland and a musical adaptation (by Julian Fellowes) in 2016, which was the first London West End musical to raise £1 million through crowdfunding.

What makes all this mysterious (apart from the fact that this quintessentially English book was written by a Scot) is that The Wind in the Willows is not a children’s book at all—neither the author nor the original publishers ever suggested that it was. Nor is it an animal story: the characters are, as one of the original reviewers, the novelist Arnold Bennett, observed, “meant to be nothing but human beings,” or as Margaret Blount in her book on animals in fiction, Animal Land, put it, “for animals, read chaps.” And boats appear substantially in only two of the 12 chapters. Even the title is mysterious—the word “willows” never appears in the book: Grahame’s original suggestion for a title was Mr. Mole and his Mates.

Kenneth Grahame at 30: a rising young banker, and at the same time one of

Kenneth Grahame at 30: a rising young banker, and at the same time one of“W.E. Henley’s Young Men,” writing short essays for the Scots Observer.

But, surely, it is a book about small and not so small animals—a Toad, a Rat, a Mole and a Badger (and therefore this must be a children’s book). If so, then these are animals who drink and smoke, own houses, drive (and steal) cars, row boats, escape from jail, yearn for gastronomic nights in Italy, eat ham and eggs for breakfast and write poetry—while Toad combs his hair, and the Mole has a black velvet smoking-jacket.

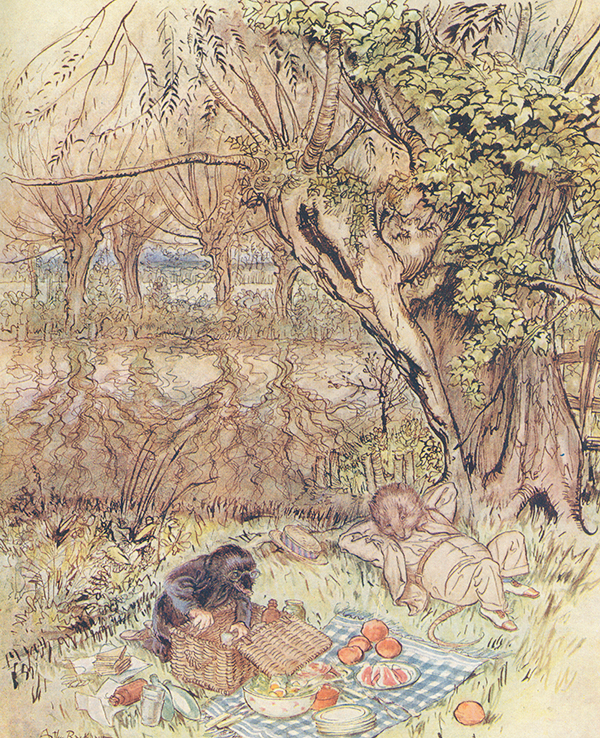

Of course, very occasionally they behave like animals. Mr. Mole, in the midst of thoroughly human spring-cleaning, briefly turns into a mole, scrabbling and scrooging his way to the surface; the aristocratic Otter, languidly enjoying a riverbank picnic (which includes cold tongue, pickled gherkins and lemonade) suddenly turns into an otter and swallows a passing mayfly.

But for the most part, the book is about a group of well-off, leisured English gentlemen. Even more importantly, the book hardly ever addresses itself to an audience of children: as Humphrey Carpenter put it, “The Wind in the Willows has nothing to do with childhood or children, except that it can be enjoyed by the young.”

“These are animals who drink and smoke, own houses, drive (and steal) cars, row boats, escape from jail, yearn for gastronomic nights in Italy, eat ham and eggs for breakfast and write poetry.”Of course, it begins—and began—as a children’s book. Like other famous children’s books—such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Hobbit and Treasure Island—it started life as a story for a particular child, and this shows most in the opening chapter. Like all these books, The Wind in the Willows grew in the writing and ended up as something quite different from, and something much more complex than, a bedtime story. But whereas Alice’s Adventures is a children’s book that can be read by adults, The Wind in the Willows is an adult’s book that can be read by children. This is because (and this also accounts for its relative lack of international success) its landscapes and cultural references are deeply embedded in Edwardian England—whereas Alice moves in a detached world of fantasy, and the many period references in that book are hidden in the background.

Into which genre does it fit? The answer to that is that Grahame ruthlessly borrowed from and played with the major popular genres of his day: the river book, the caravanning book, the motoring thriller, the rural idyll (complete with Christmas carol), the pseudo-mystic “spiritual” writing of the “decadents” (complete with miasmic pagan verse) and, of course, the rollicking boys’ adventure story. And he cheerfully parodies George Borrow, W.S. Gilbert, and Sherlock Holmes, caricatures his friends, and celebrates his own delights and frustrations.

“There’s cold chicken . . . coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscress

“There’s cold chicken . . . coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscresssandwidgespottedmeatgingerbeerlemonadesodawater—”

Arthur Rackham’s 1939 view of the iconic picnic.

One of the mystifying things for those who would try to make The Wind in the Willows into a children’s book is its attitude to adventure. Anything likely to disturb its cozy world is ruthlessly suppressed—the Mole stops the Rat from heading to the warm south in “Wayfarers All”; Toad’s rebellion is crushed by all his “friends”—and the Mole’s initial, childlike curiosity about the world is put firmly in its place in the very first chapter. As he and Rat row along the peaceful river, the Mole looks into the distance:

“And beyond the Wild Wood again?” he asked; “where it’s all blue and dim, and one sees what may be hills or perhaps they mayn’t, and something like the smoke of towns, or is it only cloud-drift?”

“Beyond the Wild Wood comes the Wide World,” said the Rat. “And that’s something that doesn’t matter, either to you or me. I’ve never been there, and I’m never going, nor you either, if you’ve got any sense at all. Don’t ever refer to it again, please. Now then! Here’s our backwater at last, where we’re going to lunch.”

This certainly concurs with the romantic idea that children’s books should be safe, and the Edwardian period has been portrayed—especially in children’s literature—as peaceful and retreatist. In fact, it was a period of political and cultural instability, change and fear. Rumors of war—especially, although not exclusively, with Germany—were common; the German battle-fleet was expanding; the Boer wars had shaken Britain’s faith in its army. No wonder the Water Rat is no fan of the Wide World.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from The Making of The Wind in the Willows by Peter Hunt, published by Bodleian Library Publishing. © 2018 by Bodleian Library Publishing. All rights reserved. Images copyright © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.