The Wild and Elemental City: Finding Life in Pandemic

New York

Megan Fernandes: “What counts as ‘natural’ says more about who counts as human.”

In front of St. Mark’s Church, two people are sparring. It is 38 degrees, but in the pandemic, any patch of square feet can sell Christmas trees, be a church stoop, host a quartet, and act as a boxing ring at the same time. E.B. White, in his famous 1949 commission for Holiday Magazine, wrote that “New York blends the gift of privacy with the excitement of participation” and I witness this dictum enacted in the city’s parks and public space during lockdown: the proximity to strangers carefully choreographed as people play music, work out, and gaze at the sky with or without each other.

I am alone for about two months in the pandemic when I begin to identify the trees of my apartment’s shared courtyard. I use a plant identifying app, sit amidst three different adolescent teaberry species, and name all of them after childhood friends. The concrete is lousy with cracks, a small ceramic statue of a tail-less squirrel its lone mascot. Kitchen routines in the apartments above echo throughout the courtyard, whistles and thuds rushing downwards as if I’m sitting at the bottom of a well.

This space, once a static backdrop of my fire escape, becomes a site of communal relief, a laboratory of vitality. When my neighbors are not exercising in the small rectangle, I lay a towel on the cement and look skyward to diagnose cloud formations, day by day, some billowing with moisture, others long and withering and devoid of planes: altostratus, stratocumulus, cirrus. Here is where I talk on the phone to my friend who tells me about the organizing lessons of Ella Baker as the growing sounds of “NO JUSTICE NO PEACE” spill into my neighborhood. Here is where I write letters about insomnia to my friend in Amsterdam, get drunk with my upstairs neighbor the playwright, where I discuss tarot and astrology with my girl, Shy, and where I pace on the phone to my sister, shot with adrenaline, after being in a hold up at a nearby bodega.

My insomnia, my adrenaline, my drunkenness, my fates, my chemical states, my altered states, my statehood, the state of the world, the state of property, nation-state, statelessness.

Soon, walking around the city, I can tell you what summer planets peer at us from space and how the benthic zones of the Hudson and East Rivers are affected by pier development. I count the trash cans standing within the neighboring four blocks of my apartment, later to be charred with fire during summer protests. I can map the direction of armed vehicles by their siren lights swimming through the avenues and still shudder at the sound of multiple vans slamming their doors during the police occupation of the city. A church burns on 7th Street and I can smell its aftermath for days. I have a real sense of Manhattan as an island, and myself, strung out and anxious, pacing between rivers.

I am alone for about two months in the pandemic when I begin to identify the trees of my apartment’s shared courtyard.

I ask myself, observing the city, what it means when someone is “in their element.” What does it mean for the city to be in its element? Elemental refers, of course, to physiological, chemical, and atmospheric building blocks, but as an idiom, it suggests a surrounding environment of comfort, flourishing, and intelligibility. To be in one’s element seems to mean existing in one’s optimal environment; a place where one feels at home, has expertise, and can thrive.

“Who can breathe free?” Christina Sharpe asks in her book In the Wake, pointing to how antiblackness functions as our climate, wherein Black people are denied breath in order for white supremacy to continue. Sharpe draws on the parallel discourses of lungs and air, citing how weather management was used as a justification to prioritize crop production over the respiratory health of enslaved Black people forced into hard labor on plantations. Sharpe also turns to Eric Garner’s devastating last words (“I can’t breathe”) and to those murdered through suffocation and aspiration in the Zong massacre. The country’s climate of violent anti-Blackness and the country’s pandemic of disproportionate death in Black and Latinx communities come into sharp relief under the lens of lung health and the archives of breathlessness. Who can breathe free? And who’s breathing is enabled by the neglect of others? Who gets to be in their element, which is another way of saying, who has access to the elements to survive?

A year ago, if you asked me what the weather was like the day before or if the moon was waxing or waning, I, along with probably many New Yorkers, would have shrugged. Instead, I could tell you the six subways I would need to take to a series of events across the city, the number of upcoming deadlines I have mentally marked, the most comfortable velvet booth for a nearby drink. Living here, I have developed a memory palace in reverse, what I now think of as a “futurity palace.” A version of what we might traditionally call the “elemental” (wind, fire, air, water) was so little part of my daily urban life. There was only an un-elemental futurity, a what’s next’ing, a compulsive protaganism. Restless, I would map what is to come.

Purist manifestos about nature have often historically been used to justify colonial and racialized understandings of the civilized/explorer/educated and the savage/wild/closer to the earth. Similarly, the “natural” in gender and sexuality studies critiques formations of the rational/know-able (Man) and the hysterical/mysterious (Woman) and heteronormative understandings of natural sexual orientations (Straight) and deviant ones (Queer). What counts as “natural” says more about who counts as human, what knowledge counts as legitimate, and what behaviors count as normative. I think of Tommy Pico’s line from Nature Poem, where he says “I can’t write a nature poem / bc I only fuck with the city” or the non-fiction writer, Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, who suggests that our bodies and relationships are our greatest research tools. These BIPOC writers actively work against taxonomies that privilege conquest and produce dominant logics. Similarly, looking at life through the elemental could help us hold the dimensionality of experience without hierarchizing it; to consider the steel of the city and the cries on the streets and weeds on the basketball courts and the grief of lost life in tandem with each other.

Elemental refers, of course, to physiological, chemical, and atmospheric building blocks, but as an idiom, it suggests a surrounding environment of comfort, flourishing, and intelligibility.

I think of the elemental as a practice in reworking relationality, proximity, and intimacy.

It has changed the way I chart this city; instead of mapping blocks only by institutions and bars, I take notes of the basswood and elm trees and thornless honey locust growing in concrete medians. I stop to face the painted images and murals of Black resistance blooming around the city and register the shift in wave turbulence of the East River. I watch the same person voguing over and over again every day in the park, with their little stereo cheering them on, as their routine builds over months. Elements “compose,” which also means elements entangle together over time, and we have had so much time this past year.

The elemental takes place in the realm of what can be materially seen, touched, or encountered together with that space of the sub-perceptual, be it a virus or the submerged disturbance in the water or urban root system, be it the heartache someone carries around with them or the mental gymnastics of race-relations one has to do when mistaken for the nanny in the park or the retail worker at Zara. This realm of incoherence taps into that part of our brain that is trying to make sense of the non-sensical, trying to place limits on the unbearable, trying to build evidence from every small thing around us to compose a world that feels momentarily safe, even if it is not.

Perhaps living in wild times means living with an incoherence we must bow to; we must not try to conquer or master, but to observe, hold, be transformed under. In their essay, “Theory in the Wild,” Jack Halberstam and Tavia N’yongo write:

To be wild in this sense is to be beside oneself, to be internally incoherent, to be driven by forces seen and unseen, to hear in voices, and to speak in tongues. By abandoning the security of coherence, we enter a dark ecology… As Nina Simone reminds us, “wild is the wind,” and the wildness of the weather, internally and externally, implies a pathetic fallacy that tethers the undoing of the human to the rage of new storms blowing in… Wildness is where the environment speaks back, where communication bows to intensity, where worlds collide, cultures clash, and things fall apart.

Feeling “internally incoherent” and “driven by forces seen and unseen” can feel violent, but these feelings are also a sign of going astray in the best sense. These feelings indicate the refusal to neatly cohere one’s self against a violent backdrop. When “new winds” destabilize us, as they are now, we should, as Simone says, “Let the wind blow through your heart.” Such is an elemental dictum.

Within this incoherence, narrative time is more fluid; unrelated elements flock together in a hallucinatory spiral. The fire of the church and the fire in the streets. The red of the sirens and the red of a laser pointer that I draw in circles on the ceiling, upside down in my bed, every evening to entertain the cat. The sparring boxers in front of St. Mark’s Church and the flashing memory of an unlikely run-in with a friend there just two Januarys ago. It is not as if the strange simultaneity of past and present, of real and imagined, did not exist before. But the pandemic’s time loop does illuminate déjà vu, sense impressions gliding together to elide our narratological ways of organizing time.

At Tompkins Square Park, there are simultaneous basketball games by neighborhood regulars, older women playing ping pong in thermal coats, kids ripping over barriers in the skate park, and joggers running in loops. All of this activity orbits two people in the center of the park practicing Qigong. They speak both Chinese and Russian, one of them in a faux fur jaguar print coat with full silver-plated streetwear jewelry, chains ringing out. The other in a bright red jumpsuit, collar popped. They look as if captives, slowly emerging from marble, their poses in mid-thaw.

I think of the elemental as a practice in reworking relationality, proximity, and intimacy.

In Central Park, two people gather giant dead leaves, stalks of willows, and sculptural branches to create rustic bouquets. People stop to inspect bench plaques and I wonder what my own would read and who I would dedicate it to. I look it up on my phone to find that each one costs $10,000. A hawk catches a tiny bird in his claws and kills it slowly. People gather under him to watch.

At the rundown tennis courts under the Williamsburg Bridge, two men, old friends, in their seventies wait their turn. One of them stretches, gazelle-like, his face in serious concentration. The other man, sitting closer to me, is drinking a Heineken and smoking a cigar. “You see that guy?” he says to me, pointing at his more Zen-like peer. “He’s not just a piece of shit. He’s the WHOLE shit.”

Washington Square Park becomes something like church where I, almost daily, sit in rapt attention to a speaker, often a member of Warriors in the Garden, a NYC activist collective of mostly young people of color. In June, one speaker said, “These are not protests. These are funeral marches. We are here to defend the dead.” We march to the opening of the Holland Tunnel to occupy that space. Up close, it looks like an altar. I have only ever experienced its opening in a car, rushing in and out of lower Manhattan, its concrete infrastructure had always struck me as ugly and intimidating, cars shifting into a claustrophobic formation. But now, crowded in a formation to disrupt the flow of traffic, I see the tunnel’s lion mouth, the way air spits and is engulfed by it. The light falls differently in this shadowy enclave, almost like how the light glitches during an eclipse.

Heading uptown another day, after marching for blocks on end, we occupy an intersection in the 50s on the west side. We sit in the street, our bodies collapsing in a simultaneous motion, blocking traffic. People eating at restaurant patios stop, mid-mouthful, to stare at us. Others yell support from the window. Someone is playing Wu-Tang. It is hot. Does anyone need water? Snacks? Hand sanitizer? Medical care? The asphalt is hot and I take in the wide streets, the wind of a fat intersection, look up at the buildings hovering above us like deities. I sit next to a young man. He plays a beat for me by smacking the sidewalk. We don’t speak much to avoid transmission. I play a beat back. We both grin like children, which is another way of saying we feel safe.

What do these entanglements from the trees to the planetary to the streets have to do with each other? In a literal sense, I am trying to practice an elemental consciousness for my city and this requires an attention to political weather, to private property and public space, to the contradictions of living a certain lifestyle and understanding the consequences of it, to understanding how aspirational whiteness has gaslit me my whole life, to studying systems of beliefs that favor the communal, to acknowledging that the New York I want post-pandemic cannot look like the New York I occupied before. What might it look like to come apart under care and guardianship? To affirm that incoherence is a legitimate reaction to our acknowledgment of the country’s violence and hypocrisies? To bow to the elemental and open oneself to new relationalities and intimacies?

Washington Square Park becomes something like church where I, almost daily, sit in rapt attention to a speaker, often a member of Warriors in the Garden, a NYC activist collective of mostly young people of color.

One day in June, a friend bikes to my apartment in the Village with a bouquet of flowers. She waves them at me as I sit on my fire escape. The purple-headed cluster reminds me of that three-headed dog from the underworld, and I disinfect the blooms before we leave to wander up to Central Park.

We walk through the dead space of Midtown with its large buildings boarded up, even peek into Grand Central Station for one minute to see it completely empty, gaping at the blue ceiling sketched in gold. When we finally hit the park, it is raining and we run up to Madonna’s Arch, an open spaced gazebo, for some measly cover from the downpour. There is a couple, a man and woman, there on a date and my friend and I pretend we can’t hear their earnest exchanges of personal histories, but of course, such eavesdropping is one of the deep pleasures of elemental city life, the porousness of sociality, the borrowing of other lives. I learn that the woman’s family is from Korea, that she plays violin, that she likes gin with cucumber slices. At some point, all of us begin to talk with each other, enclosed by summer rainfall.

In that moment, no threat is visible, even if there is one. I don’t allow it, that creeping sensation of invisible viral particles swimming around us, that slippery space where torment and element become one another, where the psychological and the molecular become indistinguishable.

I go home and greet my flowers, happy to note they have survived their disinfection.

__________________________________

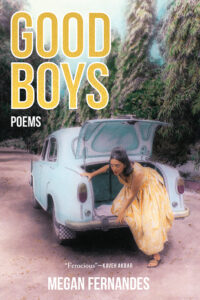

Good Boys: Poems by Megan Fernandes is available now via Tin House Books.

Megan Fernandes

Megan Fernandes is the author of Good Boys, and a finalist for the Kundiman Poetry Prize and the Paterson Poetry Prize. Her poems have been published in The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, The Common, and the Academy of American Poets, among others. An associate professor of English and the writer-in-residence at Lafayette College, Fernandes lives in New York City.