The Whiplash of Growing Up Between Two Worlds

Anais Granofsky on Code-Switching and Family Expectations

When I was eight, in 1981, my grandparents and I began to go for Sunday dinner at the Primrose Club. The Primrose Club was a swishy private Jewish social club on a midtown street, St. Clair Avenue, where the valets helped us out of our car when we arrived. Inside, we stopped at the coat check and Shirley left her ankle-length fur coat with the attendant.

For my first visit, I was wearing a velvet-trimmed dress from the closet in my room and new shiny shoes that pinched my feet. Shirley gave me a final once-over with approval and took Phil’s arm. Then we climbed the staircase and entered a massive dining room overlooking the twinkling lights of the city below. I had an impression of all-dark wainscotting and marble, offset by white tablecloths and shined silverware reflecting the soft light from the overhead chandeliers. Old-school waiters wore tuxedos and white gloves and knew my grandparents by name. It all felt so impossibly sophisticated.

My grandparents’ table was strategically located on the far side of the room, so the walk to the table was epic and exhilarating. My grandparents were so glamorous that it felt like all eyes were on our arrival. I was proud to be with them and walked with my little head held high. Once we were seated, other guests approached my grandfather to ask for an audience or to commend him on a recent donation to a Jewish charity. He was powerful and connected, and everyone knew it. He made the rounds in the room like a newly elected politician with a suave Sinatra vibe. My grandmother, coral lipstick perfectly applied, played the part of his loyal spouse.

When the inevitable question arose—who was this little brown girl?—my grandfather fell uncharacteristically quiet. Shirley didn’t equivocate: she introduced me as their granddaughter without hesitation. She had a direct look in her eye that I came to learn warned her interlocutor against being indiscreet. I noticed the flash of surprise across people’s features, quickly replaced by tight smiles and good manners. I wasn’t embarrassed by their attitudes—they were unfailingly polite and complimented me on how “cute” I was—but it made me acutely aware of the shape-shifting that was once again required in order to fit in. It reminded me that the rules in this world didn’t necessarily benefit a little Black girl like me, so I was going to have to learn them quickly.

But I think more than anything, I just wanted my grandparents to be proud of me. So I listened intently as my grandmother taught me which silverware to use and how to lay a cloth napkin across my lap. How to sit up straight and look people in the eye. Then the meal arrived. This became the part that I looked forward to all week. Each course was served by several waiters who revealed the food from under a silver cloche, accompanied by a puff of steam. Dinner began with matzo ball soup (soon my favorite), then brisket and potatoes covered in gravy, and finally Jell-O for dessert. I loved every minute of it, reveling in the glamour and in the fiction that I belonged. Some nights I’d return home to my mother from the Primrose Club carrying doggy bags, having changed back into my old clothes.

My mother would get indignant when I tried to give the food to her. “I don’t need their damn leftovers. Who do you think I am? We’re not a charity case.” I would backpedal: “I know, Ma. I just saved some ‘cause I thought you might want to try it.” Then she would throw it in the garbage. “Well, you thought wrong.”

I was old enough to understand the inequality and hostility that the people I loved felt for each other, but too young to do anything about it.

She had wanted me to know my father’s family, but every time I returned I felt her simmering rage at being excluded. She knew it wasn’t my fault, but I could tell by the way she looked at me that she hated me a little for it anyway. I always lied and told her how much I hated my Bridle Path visits, and she would eventually, gratefully believe me. The two of us would curl up on the couch and watch Sunday Night Football. We loved the Pittsburgh Steelers and they were having another rough season that year, so we cheered them mightily. We were happy to just be together again. The next morning, I would find the food containers back on the counter, empty.

*

These visits and dinners had been going on for some time, and I was beginning to settle into my Bridle Path role. Until one Sunday evening, at the end of one of our Primrose dinners, I stood waiting by the downstairs kitchen that served the club’s ballroom as my grandmother collected her coat from the coat-check girl and my grandfather finished shaking hands in the dining room. Bored, I wandered down the hallway toward the loud music. Through a door I watched a bar mitzvah taking place in the ballroom. The room was packed and the bar mitzvah boy was being lifted up on a chair, a bright spotlight on him as he was passed around the room. Music pulsing, his family dancing and sweating in a joyous circle beneath him. I had never seen a kid have such an exuberant celebration of family and tradition. I yearned to be lifted into the light like that, surrounded by generations.

From the kitchen, several busboys exited with trays of food for the party and I suddenly realized that the downstairs kitchen staff were mostly Black and brown. They looked like people in my neighborhood; they looked like my family, like my mom. If she could see me now, pretending to be some rich little white girl. I suddenly became terribly self-conscious. What if someone recognized me here, dressed like an imposter in my velvet-trimmed dress and too-tight shoes. What if I was found out at home and people knew that I was here with my Jewish grandparents? I heard what people in my neighborhood said about Jews. And now, suddenly, embarrassingly, I felt caught out. I was divided and didn’t know which part of myself was the real one. I stepped back into the shadows as the waitstaff passed by, taking no notice of me. Then my grandparents called to me and I quickly slipped away.

*

After a few years, the whipsawing of worlds began to take a toll. I was always trying to figure out where I belonged and what was expected of me. I know now that this was me code-switching. Back then, it was just trying to fit in and be loved. When my grandparents would drop me off after a visit, I would insist that they let me out down the block from my house. My mother’s voice in my head told me, We don’t need people all up in our business. They don’t need to know nothing. I made sure that I never mentioned my grandparents when I was in my neighborhood, never talked to my friends about where I went on weekends. They were never overtly anti-Semitic, but there was talk of “Jewish landlords” and “rich assholes,” so I learned early on not to call attention to the fact that I was half Jewish.

At that point I didn’t even know what being Jewish meant to me, or if I even was Jewish. With my grandparents, it was the opposite. Whenever I went out with my grandmother, it was made clear that the slang I used at home was not welcome with them, so I changed up my language and cadence accordingly. I absorbed the negative images white people had around being poor and Black and the ones Black people had around being wealthy and Jewish and I wondered who I was in all of that. And who I wasn’t.

When I was ten, a boy around my age moved in next door to my grandparents and we quickly became friends. He was British and his dad was a big executive at a bank, so he moved a lot. Harry was long and lanky and had a mop of blond hair that hung in his face. When he asked if I lived at my grandparents’ house I lied and told him I did. I don’t know why I did it and, even as I was doing it, I knew it was totally unsustainable. I guess none of my friends at home knew who I was here, and I was curious to find out who that girl was. Harry and I would meet up at our adjoining back gardens or swim in each other’s pools. We would hide out in his mother’s fur closet, kept cool to suit the sable, eating snacks made by his housekeeper. I donned a cloak of invisibility and slipped, disguised, into his luxurious world.

Untethered from who I was, it was lonelier then I expected it to be. Harry was funny and self-deprecating and we liked each other a lot. But I continued to lie to him, unable to show him who I really was even when I wanted to. When he had to move again several months later, I was desperately happy to see him go, relieved that my lie hadn’t been found out. I had already begun to ruthlessly compartmentalize my life according to who I was with: my mother (balance), grandmother (presentable), father (easygoing) and friends (street). It was a moving target.

The tensions of balancing social expectations, racism, classism and family history grew stronger over the years as I became more aware of the opportunities I had that my mother and friends didn’t. I felt lucky and ashamed. I was old enough to understand the inequality and hostility that the people I loved felt for each other, but too young to do anything about it.

__________________________________

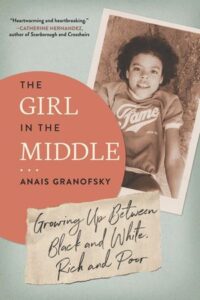

Excerpted from The Girl in the Middle by Anais Granofsky and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2022.

Anais Granofsky

Anais Granofsky is an actor, director, producer and writer. Best known for her role as Lucy Fernandez on Degrassi Junior High and Degrassi High, she has directed and starred in a number of films. She is also developing a fictional TV series loosely based on her childhood. The Girl in the Middle is Granofsky's first book.