The Wall of Silence: On Trying to Talk About Palestine, Israel, and the USA

Philip Metres Seeks Unoccupied Spaces for Conversation

“The fact that we are here and that I speak these words is an attempt to break that silence and bridge some of those differences between us, for it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken.”

Article continues after advertisement–Audre Lorde, from “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”

*

In his provocative 2005 Christmas card, Banksy paints in pastel a familiar Biblical pastoral scene, but with a modern twist. Joseph, holding a shepherd’s crook, and Mary sitting on a donkey, pause—their way to Bethlehem obstructed by a massive, forbidding wall. The wall—replete with modern observation tower and brushed by faint graffiti—rises so high they can’t see what’s on the other side. Beyond the wall, in the distance, a star rises. The actual wall that Israel began to build in 2002 not only divides “sides,” it also snakes through towns like Bethlehem, separating people from each other, from their own land. It’s been called many names, depending on your point of view: security fence, separation barrier, apartheid wall.

This wall is the visible sign of another wall, built in equal parts of silence and noise, which separates the United States from the realities of Palestine and Israel. What words can one summon that might circumvent that wall? The truth is that the question of Palestine is far closer than many of us might have ever imagined or admitted.

Ever since my sister studied at Bir Zeit University in 1993 and came back with haunting stories about the brutality of life under military occupation, I have been trying to find ways around that wall, to ask the question of Palestine. A few years after, I found myself interviewing a young Palestinian from Gaza who had become a graduate student at our Midwestern university. I emailed him a draft of my news story about the tortuous journey of some Palestinians to attend graduate school. He read it carefully and asked to meet again at my house. After sitting and having tea, he set aside the cup. With a mix of fear and sadness in his eyes, he said that he needed to be written out of the story. The details about his journeys to college and then to graduate school—some of which skirted Israeli rules—could be used against him and others.

It struck me with such force—that the very details that demonstrated the absurdity of the Palestinian situation and the capriciousness of Israeli power would have to be removed from this story. But I wanted to help him, not render him and people like him even more vulnerable.

In situations of oppression, people find in silence a form of tentative protection. It’s a provisional and temporary safety, of course, but the risks sometimes seem far worse. In colonial contexts, and in situations where states extend their power into the private lives of those they rule—from the Soviet Union to China, from Northern Ireland to Palestine, public speech goes into hiding. In Northern Ireland during the Troubles, where paranoia and terror were permanent guests, silence was the golden rule: “Whatever you say, say nothing.”

What I’m interested in exploring is another kind of silence. Whenever I share something on social media about matters relating to Palestinian rights, history, or the quest for freedom, it is greeted by another kind of silence. Is it the silence of apathy? Confusion? Fear? Or the sense that taking any position could lead to hurting someone else? Our peculiar moment, in the new Age of Distrust, in the land of social networks, seems to offer us only polarizing extremes—on all manner of issues. For example, “You’re with X or you’re against us.” Your choice is to like this post or not like it—and you will be judged. The posts that move the fastest and farthest run on the fire of hot takes. The silence about what’s happening in Palestine-Israel, or Israel-Palestine, in the country of argument, in the land of free speech, in the birthplace of Twitter, is what I want to open.

I have wanted to parse out that silence for a long time now, and it is partly the reason for my writing Shrapnel Maps (Copper Canyon, 2020), which gathers over a decade of poems, texts, and images that concern Palestine and Israel. It was a difficult book to write. To speak publicly about it involves a measure of risk—in a time when conversation itself is often weaponized or perceived as violent. But silence’s safety is provisional and its own kind of danger.

Audre Lorde writes: “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?…” The question I ask myself, over and over, is: who will be lost in my silence? What sort of words do I need to open it?

When my sister arrived in Palestine, the first Intifada, an uprising against the Israeli occupation, was ongoing. As she went shopping in Ramallah, an Israeli settler drove down the street. “He was in a big truck,” she recalls, “and he had his head out the window and he was shooting a gun wildly into the air. Some Palestinian grabbed me and pulled me into a shop, and they were all laughing. That’s when I learned the Arabic words for ‘what happened’ and ‘settler.’”

In situations where states extend their power into the private lives of those they rule—from the Soviet Union to China, from Northern Ireland to Palestine, public speech goes into hiding.

She was there to study Arabic language, but her education was far more than about past and present tense. She kept telling stories that seemed like they were written in a sci-fi dystopia: stories of torture of prisoners, indefinite detention, humiliating checkpoints. I wondered, given what I’d learned about the persecution of Jews, about antisemitism and the Holocaust, whether she’d drunk some radical Kool-Aid. I struggled to listen. Wasn’t Israel the expression of Jewish nationalism, the creation of a national home? After all, how could a people who have faced exile and concentration camps and inhuman brutality turn to exiling, imprisoning without charge, corralling people into ghettos, torturing prisoners? At the time, it made no sense. But my sister stood by the truth of what she witnessed, what she’d come to understand, and so I had to embark upon my own journey of self-education.

I began to fill in the gaps of my understanding were not mere absences in my education, but part of a structure of active silence and noise. Attending conferences hosted by organizations like the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC); finding graduate courses like “Resistance Literature” taught by Purnima Bose; joining Committee for Peace in the Middle East (CPME); and building friendships with Palestinians, I began to see other realities. The work of Palestinian scholar Edward Said was a touchstone for me, especially Orientalism, Culture and Imperialism, and The Question of Palestine. When, in 1995, Edward Said delivered his lecture “On Lost Causes” to a packed auditorium at Indiana University, the only thing I remember was how Said kept getting interrupted by protestors, often standing up in the aisles, shouting at him. Every nation, of course, has its saints and psychopaths—and most of us stand somewhere in the middle.

Despite the shouts of those protestors, the intentional silence or outright anger that would greet me and the others who worked to raise awareness about the issues that plague Palestinians—from home demolitions to indefinite detention, from refugee rights of return to killings at the hands of Israeli Defense Forces—we kept trying to change minds and change policy. We showed films, circulated petitions, wrote letters to the editor, invited Ali Abunimah to speak, organized street marches, did poetry readings, and raised funds for organizations working for peace, justice, and human rights. Mostly I just tried to show up, to learn from Palestinians, make friends, and to be part of building something bigger than our small voices.

In graduate school, I read the haunting Men in the Sun, by Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, which narrates the journey of three Palestinians who risk illegal transport to Kuwait to earn money for their families. The most dangerous leg of their multipart journey will be to climb inside an empty water tanker as it crosses a border. The conditions inside the tanker are suffocating, but the Palestinian driver Abul promises the stop will be short. Once inside the checkpoint office, however, the border guards tease him about his virility (he’s been castrated by a war injury), and he pauses, trying to defend himself. By the time he drives them past the border, all the men have perished inside. Abul laments what’s happened but blames the victims:

The thought slipped from his mind and ran onto his tongue: “Why didn’t they knock on the sides of the tank?” He turned right round once, but he was afraid he would fall, so he climbed into his seat and leaned his head on the wheel. “Why didn’t you knock on the sides of the tank? Why didn’t you say anything? Why?”—The desert suddenly began to send back the echo: “Why didn’t you knock on the sides of the tank? Why didn’t you knock on the sides of the tank? Why? Why? Why?”

But it was never that simple. The choice was far starker for the Palestinian migrants inside the tank. If they knocked, they could get discovered and deported, or worse. And maybe, in fact, they did knock, but he could not hear them—lost inside the office or locked in his own shame.

Men in the Sun depicts the extreme precarity of Palestinian existence and the outrage of their suffocation inside a prison not of their own making. And, if that weren’t humiliation enough, they are blamed for their own deaths. The driver rationalizes his own failure to move quickly enough. Perhaps the question isn’t “Why didn’t they knock on the tank?” but rather “why did no one listen?” Men in the Sun cuts in all directions—against Israel and its displacement of Palestinians; against the Arab countries that treat Palestinians as non-citizens or worse; and against Palestinians themselves, who believe their silence might protect them. But I thought most of all about my position as an American citizen, in a country that has never treated Palestinians as equals to Israelis, about whether I was more like the driver who, in a fit of distraction and shame, would simply forget about Palestinians suffocating inside their metal prison—either crying out and not being heard, or trying to be silent to survive.

A prolific fiction writer, Kanafani also became the spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine in the last five years of his life, a resistance organization calling for a single binational state. After some particularly bloody PFLP operations, including the Lod airport massacre, Israeli agents assassinated him at age 36, along with his 17-year-old niece, in 1972. Kanafani’s path to resistance—the “commando who never fired a gun,” as one obituary wrote it—had begun when he and his family fled Acre and became refugees in 1948.

Mostly I just tried to show up, to learn from Palestinians, make friends, and to be part of building something bigger than our small voices.

Of course, his path was not my path. I am interested in forging a nonviolent way to engage in the struggle for justice, freedom, and equality—as are most Palestinians. In 1990, as the US beat the drums of war against Iraq, I wrote a conscientious objector statement to declare my philosophical and religious (not to mention political) refusal to bear arms. But stateless refugees face a far grimmer reality, and far starker choices than my staying home in a time of distant imperial war.

Ten years after my sister’s first summer at Bir Zeit, she returned. In a whirlwind romance with a man she’d met a decade earlier, she got engaged. Our family made the trek across the world for the wedding in a little village in Palestine. It was a surreal and magical—to be in the place that I’d heard and read so much about. I tasted a tiny bit of the bitterness of living under military occupation, alongside the savor and sweetness of Palestinian family life in the village. I had guns pointed at me at checkpoints, saw the separation wall that devoured part of my brother-in-law’s land, and roads torn up by military bulldozers. But I also danced the dabke, ate until I nearly burst, and felt the love of a family who accepted our family as part of their own. Though we met only once, I have never forgotten them.

At John Carroll University, I developed a course called Israeli and Palestinian Literatures that explores, in a contrapuntal structure as Edward Said proposes, the predicament of this co-claimed land. I wanted to do what I could not to propagandize my students, but to offer them ways to understand the origins of this problem, to be implicated in it in the way that the US is implicated in it—and, if possible, to participate in changing the future. My approach, from the start, was dispassionate. Although I was passionate about it, I’ve always believed that the best way to teach is to create spaces for students to have their own experiences, create their own questions, come to their own conclusions, and make decisions based on that process of discernment and praxis.

That’s why, the following year, when a local Orthodox Jewish woman inquired about my course, my first impulse was to invite her to be a guest speaker in my class. After all, my goal was to offer students a range of inputs, and I knew from our email conversations that she could represent a certain view in a way that would be more difficult for me to pull off—to make a religious case for Israel. She declined my invitation, saying she couldn’t come to my class because, in her words, Palestinians are not a people. After she sent me an ongoing series of inflammatory emails, my patience waned, and I said I couldn’t communicate any further with her. In my one mistake in tone, I told her that I wished her well “but not her racism.”

This response triggered a series of emails to the president and every member of the administration at my university, accusing me of antisemitism and preaching hatred toward the Jewish people, asking that my course be canceled immediately. I was, of course, horrified and afraid—afraid for my future. Had I stepped over an invisible line of silence that I would pay for with my job? Mostly, though, I was horrified, because I’d made every attempt to create space for a variety of Jewish narratives and perspectives on Israel, and because I took the accusation of antisemitism seriously. Had I not been fair enough to her, to her cause, for Israel? Israel, after all, is full of its own stories and narratives worth hearing—but had I not explored that complexity fully enough?

In the end, I was deeply gratified that the administration, after studying my course materials, supported the course and my progress toward tenure. I was lucky. Other faculty whose work was arguably more threatening to the status quo on Israel have not fared so well. In 2007, Norman Finkelstein, the child of Holocaust survivors, was denied tenure at DePaul, despite department and university committee votes in his favor and having numerous books and articles to his credit. Some have surmised that Finkelstein’s takedown of Alan Dershowitz’s The Case for Israel as a plagiarism of a hoax text (Joan Peters’s From Time Immemorial) led to Dershowitz’s direct intervention on the tenure case.

Seven years later, after outside intervention, Palestinian scholar Steven Salaita “unhired” by University of Illinois on the basis of “uncivil” Tweets during Israel’s latest war on Gaza—a war which killed over a thousand civilians, destroyed forty mosques, targeted crucial infrastructure like water filtration plants, and set Gaza on a path to being uninhabitable. Evidence suggests that donor pressure led to the decision to remove Salaita. Did I like Salaita’s Tweets? His tone is not my tone, but that doesn’t mean they were grounds for firing. And what if incivility in the face of barbarity is actually more human than silence?

Most violence doesn’t begin at a traffic stop or with an itchy trigger finger, but goes all the way back to legislative assemblies, corporate boardrooms, and executive offices.

The work of organizations like the Anti-Defamation League and the Lawfare Project has actively suppressed speech about Israel and Palestine. Faculty and students alike have been defamed and sued into silence. At the same time, states have begun to pass laws that outlaw support of the Boycott, Sanctions, and Divestment (BDS) movement, a nonviolent strategy to pressure Israel to change its policies toward Palestinians. Americans have literally lost their jobs for failing to sign a loyalty oath to another country.

While I understand that some fear that BDS is a strategy of demonizing Israel, I am reminded of Colin Kaepernick’s dilemma, when American football fans became outraged after the quarterback took a knee during the national anthem to protest police violence against Black people: in what way can Palestinians protest their unjust treatment that would somehow not be deemed offensive or dangerous? In what way can Palestinians cry out against the impossibility of their lives as disposable persons, people without a country?

Some years after that unforgettable visit for my sister’s wedding, I began trying to find a shape against my own silence. I had little thought of what was taking shape as I wrote the first poems about that wedding and all that we’d witnessed in “A Concordance of Leaves.” On the final day of my course, I always wanted to share something personal about why I felt responsible to teach this conflict, to share something of what I’d witnessed in my time there. What began as a short slide show became a long poem. Over the years, other pieces of the shrapneled map that is Palestine and Israel would reveal themselves.

Since Shrapnel Maps was published in April, I have given a number of Zoom readings. Often, I begin with this one:

[ Family ]

At the Catholic university, a speaker clicks through slide after slide of barbed wire, cattle-chute checkpoints, and walls. His mantra is occupation. What threatens the Christians, he concludes, is what threatens Palestinians. A woman stands up. I wanted to let everyone know, she says, that this talk was FULL of SPIN. (I can’t see her, she’s behind me, I’m afraid to look back.) The truth is the OPPOSITE. (My heart goes out to her, standing in the heart of another country.) The reason for the wall was that people were being ATTACKED, she says. BY TERRORISTS. After all, the Arabs sold the land, it was too much trouble. (I shrink back in my seat, shake my head.) And at a Catholic school, you should KNOW what the Church has done, especially during World War II! Then a man gets up (I can’t see him, he’s behind me, I’m afraid to look back). The Jews bought a tiny bit of land, but the rest, the rest was STOLEN! (My heart goes out to him, standing in the heart of another country.) BUT! he says. THEY did not buy everything, even if they buy Congress! (I shrink again.) She says, YOU have FOURTEEN ARAB countries! Can’t we have just ONE? THEY should take you in. He says, but this is OUR land! Why should we have to leave? Because EUROPE took it from us? That is why we fight! (What about peace? someone mumbles.) He says, how can you negotiate over a pizza when one side continues to EAT! She says, how can you negotiate over a pizza when one side is trying to STAB you with knives! It goes on like this for a long time. Years. Decades. Generations. I sit like a child at the table, watching parents grip utensils, spit words like shrapnel. I hate

how I love them.

Ashamed, I look down, unable

to bury the hot metal.

This poem, in the form of the Japanese haibun, recounts an incident that happened at my own campus, when a local community member gave a talk about the challenges facing Palestinian Christians. Much of it is nearly verbatim. I live in University Heights in a predominately Jewish Orthodox neighborhood. Every day I’d encounter my neighbors, in awe of their rituals and community, and would try to understand them when differences arose. Israel was nearby, in more ways than one. Many of my neighbors have come from Israel or will be moving to Israel.

In the poem, I wanted to capture that deep discomfort that accompanies many public conversations in the US on Palestine and Israel. As a poet, I wanted to sit with that discomfort, inside the stories of these two people, to try to imagine with compassion their worlds. That night I heard the pain of the Jewish woman as she asserted her own story, but also how that pain caused her to rationalize the suffering it caused Palestinians. I heard the pain of the Arab man as he rebuffed the Jewish woman’s narrative, and how his pain seemed to rebuff the Jewish woman’s story. Finally, I heard my own pain, my inability to react to the situation as it unfolded.

“Family” also confronts the silence of the bystander. Of the three responses to threat—fight, flight, and freeze—the bystander is the one who freezes. Freezing is a self-protective reflex, but in the end it obstructs intervention in what is a situation of conflict or violence. As someone who instinctively prefers peace over conflict, I recognize that I have sometimes stood back, freezing in fear, rather than moving forward to play a more constructive role. I don’t want to condone a peace without justice, which in the end only serves the powerful. The poem acknowledges the insufficiency of this silence, but does not offer another way. (Other poems in Shrapnel Maps try to do that work.)

Of course, during the real life incident, I froze. Instead, I wish that I had welcomed my Jewish sister at my university and thanked her for her perspective. I know how important it is to make spaces safe for Jews and Jewish expression, and to oppose anti-Jewish hatred. I wish that I’d welcomed my Palestinian brother as well, to thank him. I know the history of Orientalism and anti-Palestinian hatred and if we want to create a just peace, we must grapple with the legacy of empire, colonial erasure, and demonization.

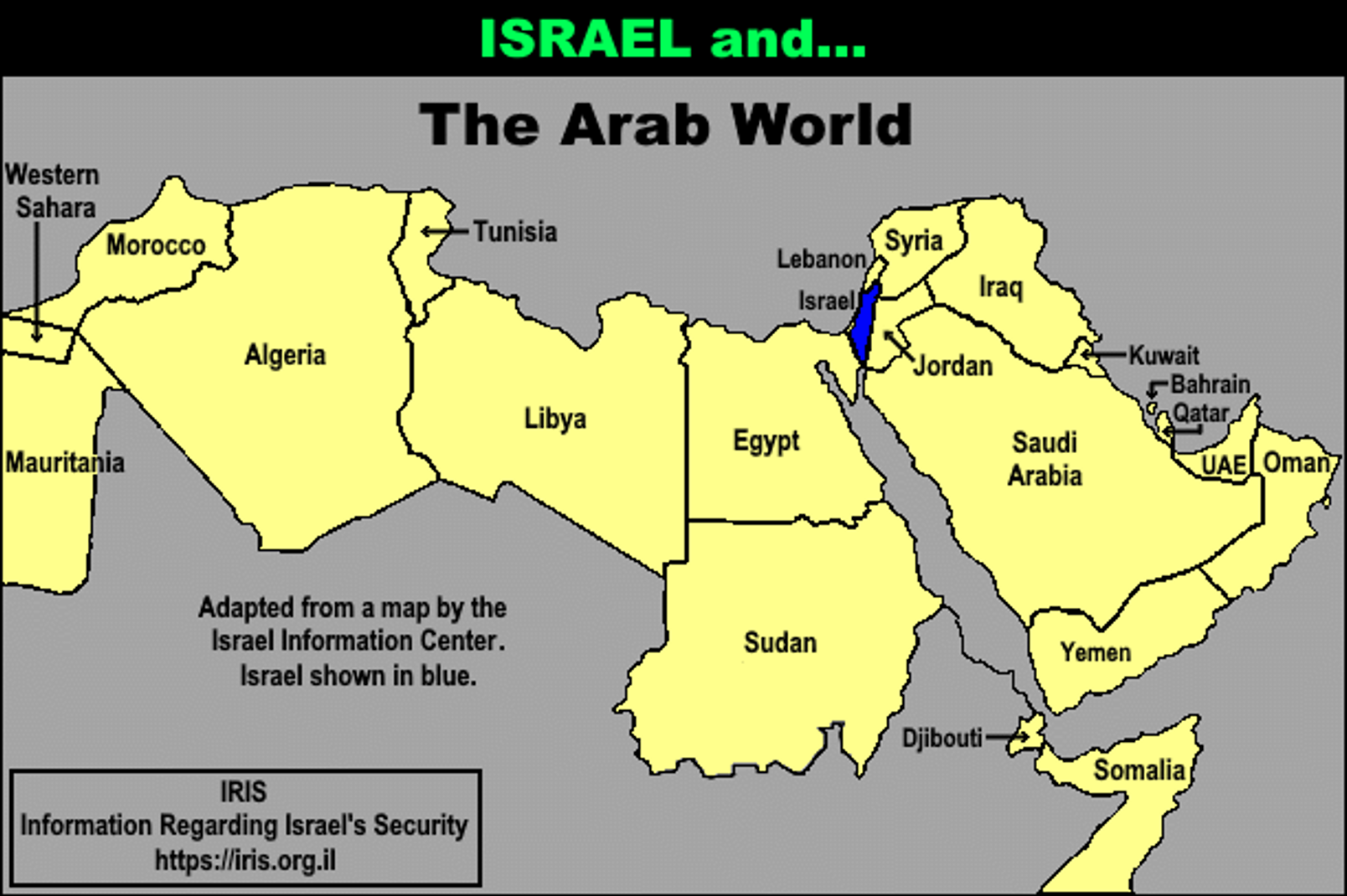

What would have happened, if we had been able to talk afterward? Their stories are so different, grounded in two different realities. In a material sense, they are. The state of Israel is prosperous, privileged, militarily strong. That doesn’t meant that Israelis don’t have their own struggles and history of traumas—both caused by the Holocaust and by expulsions from Arab countries after the founding of the state. They face their own kind of precarity, and the general threat of the “neighborhood.” The psychic map of that reality looks something like this:

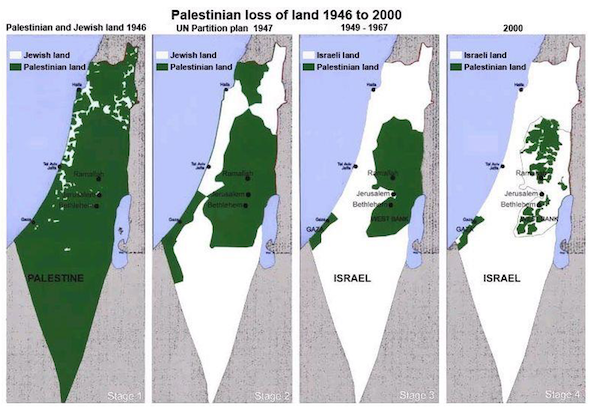

However, most of Israel’s non-Arab citizens largely conduct lives in which Palestinians are an abstraction, part of a generalized sense of a world that opposes them. Palestinians, on the other hand, always have to deal with the reality of Israel—whether they are refugees, Israeli citizens, or living under military occupation. The Israelis they meet today are nearly always military figures imposing their will on their lives. For Palestinians, the Nakba of 1948—the catastrophe that led to the dispossession of over 700,000 Palestinians, the destruction of over 400 villages, and an ongoing exile—continues. Year by year, Israel annexes more land, dispossessing more Palestinians, and diminishing future Palestinian sovereignty. Their reality might look something like this:

Neither of these maps tells the “whole” story (and perhaps there is no “whole” story anyway)—but they are the images that rhyme with the dominant narratives carried by each people.

In the United States, we are moving into a moment in which, paradoxically, we’re more polarized than ever, yet at the same time, we’re confronting the very basis of our history. I recently saw a map gif that struck close to home, and echoed the map above:

I got to fit in stuff like this map of what ~150 years of colonization looks like. (Native American land loss from 1776 to 1930) which took me forever to animate so I made a gif of it pic.twitter.com/4XLX3KfGKq

— Ranjani Chakraborty (@ranjchak) October 14, 2019

Article continues after advertisement

What the Dakota Access Pipeline protest and Black Lives Matter movement have done to transform the US conversation about white supremacy and colonialism is what many groups have been working to do to understand the US role in Israel and Palestine over the past century. We need to understand systemic and legalized oppression and violence. Most violence doesn’t begin at a traffic stop or with an itchy trigger finger, but goes all the way back to legislative assemblies, corporate boardrooms, and executive offices—a kind of ongoing set of protocols of control that lead, invariably, to spiritual and physical death. We need to find ways of calling for accountability, constructive engagement, and nonviolent means of persuasion.

Silence is not just my own personal failing. It’s a national condition, this silence about the longstanding, univocal, and unconditional US support for Israel. Reasonable people can disagree about foreign policy. But to completely neglect the humanitarian and political implications of this policy for Palestinians is to ensure that the US stands against an occupied and stateless people, who have no leverage in its negotiations with its ally. This is, in part, how violent resistance comes to seem like the only option.

There is almost no debate about the billions and billions of dollars of US military aid to Israel offered without conditions. And despite the fact that Trump was uniquely damaging to the cause of Palestinians—from the move of the US embassy to Jerusalem to the so-called Deal of the Century to the legitimizing visit of Mike Pompeo to an illegal Israeli settlement in the West Bank—a President Biden administration does not offer Palestinians much hope either. Thus far, the empire has spoken only one story.

How do we break the wall of silence that empires and states build, to hear other stories? I wanted my book Shrapnel Maps to be more than a book of poems, but another key to open a door in the wall of silence. Given the predicament it explores, and the lives impacted by our own national silence, and yet knowing the deep pain of both Jews and Palestinians, I wanted it to become a careful invitation to a conversation. From my own position as an Arab American, as a Catholic, as a poet—someone outside but proximate to these identities and experiences—I’ve tried to inhabit a stance that would model a way of listening to Palestinians and to Israelis.

In Shrapnel Maps, I also wanted to shine a light on Palestinian and Israeli activists whose courageous work for a just peace offers us another path. People like Rabbi Arik Ascherman, who co-founded Rabbis for Human Rights, and whose defense of defenseless Palestinians is highlighted in “According to This Midrash.” People like Huwaida Arraf, who co-founded the International Solidarity Movement, and whose outlandish bravery is captured in “The Dance of the Activist and the Typist.”

Friendships became the ground of much of Shrapnel Maps. My friendship with Nahida Halaby Gordon, one of the many regular visitors to my course to share her harrowing story of exile and erasure, led to the poems in “Returning to Jaffa.” It was from her that I learned about the disappearance of the Jaffa municipal archives during the Nakba, which ensured that Palestinians would not be able to confirm their right of return to the most populous Arab city in 1948. My friendship with Fady Joudah, an incredible poet and translator of exquisite grace, opened my eyes to what I could not see. Even his email, which includes the name of the village that his people were expelled from, became a key to a door of the history of the Nakba.

As I was completing the book, I recognized the many silences, the many blind spots, which the work would invariably contain. I wanted to create a text that might create spaces where silences could be broken, where people could be seen. As I write in “Future Anterior,”

13. What do you want others to know?

Tell them that we exist.

That we exist,

even between the words of their text.

That includes, of course, my own text. The response to Shrapnel Maps has been various. There have been some beautiful, heart-opening responses from all corners of the world. One, among many, shared that “the written, that is to say unspoken, Hebrew word for ‘hope’ is the same as the word for ‘despair.’ This is a brave book.” A poet from Gaza named me a Gazan for its depiction of Gaza. And there has been at least one deeply critical review, to come to grips with the traumatic pain that many Palestinians feel, as they are disappeared even by supposed allies. I understand all the reasons for such criticism, and feel sorrow that the work failed to reach them.

So how can we make our way around the wall, and encounter Palestinians and Israelis working for justice and peace? The COVID pandemic, paradoxically, has opened up new pathways of engagement and encounter. From your own home, you can “travel” beyond the walls and into the streets and homes of those impacted. US organization Eyewitness Palestine has created virtual delegations to visit its partners on the ground, from Jerusalem to Bethlehem to Jaffa. Breaking the Silence, an organization run by veterans of the Israeli Defense Force, continues to share its research on the impacts of the military occupation on the lives of ordinary Palestinians. The progressive Jewish organization Encounter offers programs designed to invite Jewish leaders to “expand their view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and to be a positive force for communal change.” Progressive organizations with cultural or religious ties—from Jewish Voice for Palestine (JVP) to Friends of Sabeel North America (FOSNA), a Palestinian Christian organization—shares ways to learn more and get involved in making change. Human rights organizations from Al-Haq to B’Tselem monitor Israeli human rights violations. Al-Shabaka’s new podcast Rethinking Palestine explores political analyses.

For those interested in Palestinian writers, the 2020 Palestine Writes Festival featured an extensive program of Palestinian writing, in English and in Arabic, as well as radical luminaries from Angela Davis to Robin D.G. Kelley. I asked fiction writer Susan Muaddi Darraj, one of the organizers, what it meant to be part of this festival. She noted that the online format enabled triple the registrants to sign up, to “welcome all people in the diaspora to participate.” She noted, poignantly, that “Palestinian people are a living poem… we encapsulate so much beauty and tragedy and power. I’m excited to join everyone this week and celebrate that.” Naomi Shihab Nye wrote that the festival “means the world. It’s our big, wide, deep family.” Tariq Luthun called it “a reunion of sorts… that allows us to celebrate celebrate our culture first and foremost, but also enters the archival discourse to further assert our place in the world.” Similarly, George Abraham shared that it was “a space which connects us despite the crimes against our diaspora, especially within literary institutions; it has been a revitalizing and grounding force for me, in a time that seems never-ending in its distancings.”

One of the first events, moderated by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, featured two eminence grise writers, Ibrahim Nasrallah and Mahmoud Shukair, whose lives have spanned the entire Palestinian Nakba. Nasrallah nodded to the predicament of diaspora, telling us “it doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to Palestine. You live in your homeland as long as it lives in you.”

In the poetry reading at the festival, I found myself moved by spoken word poet Rafeef Ziadeh’s “Three Generations,” by Fady Joudah’s original poem in English and his self-translation, by Fargo Tbakhi’s futurist visions of a Palestine in 2148, by Dareen Tatour’s impassioned explanations of the condition of imprisonment. Tatour had become a cause célèbre when she was arrested and imprisoned for incitement due to a poem that she had written, “Resist, my people, resist them.” But here she was, not a cause or a concern, but a flesh and blood writer, sequestered at home with a headset, trying to explain what words struggle to depict—the mostly invisible, silencing condition of carceral discipline that the colonized face and sometimes internalize. And there, as well, was Jahani Salah’s notion of “writing the world to right the world.”

Suddenly, Palestinian writers have breached the wall of American literary acclaim. Adania Shibli’s harrowing Minor Detail, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, was a finalist for the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2020. Naomi Shihab Nye was named the Young People’s Poet Laureate in 2019. The debuts of poets George Abraham (Birthright) and Jessica Abughattas (Strip), and fiction writer Zaina Arafat (You Exist Too Much) all emerged in 2020. The wall is beginning to show cracks.

When the wall is breached, the question of Palestine will not be some distant enigma. It will seem as close as our own American history. As we begin to break the silence of our own history and systems of control, we will begin to see its projections and erasures all around us. What walls in us are ready to be broken? What fields will be visible unfolding before us? Can we reach a place where all can be seen, and all can belong? How will we speak of it?

________________________________

Recommended readings and viewings on Palestine and Israel

Audio Documentary

The Lemon Tree by Sandy Tolan, (which he expanded into a book) is a good primer, and a model for reparation and reconciliation at the interpersonal level.

Histories

Side by Side: Parallel Histories of Israel-Palestine: a binational account.

There are many important histories, including by Rashid Khalidi, Meron Benveniste, Benny Morris, and Ilan Pappe. See also these ten histories feature at Lit Hub.

Documentary Films

Arna’s Children

Budrus (nonviolent uprising against the wall in the village of Budrus)

Encounter Point (powerful documentary about the Parents Family Circle, a grief group)

Five Broken Cameras (nonviolent uprising against the wall in Bi’lin)

Naila and the Uprising (role of Palestinian women in the first Intifada)

Feature Films

Chronicle of a Disappearance

Divine Intervention

Miral

Omar

Paradise Now

Salt of This Sea

The Time That Remains

Nonfiction

The Question of Palestine by Edward Said

After the Last Sky by Edward Said

Palestine Walks by Raja Shehadeh

The Yellow Wind by David Grossman

The Way to the Spring by Ben Ehrenreich

Palestine is Our Home by Nahida Halaby Gordon

Gaza Writes Back: Short Stores from Young Writers in Gaza, Palestine ed. Refaat Alareer

Palestine As Metaphor: Mahmoud Darwish

Novels/Stories

The Smile of the Lamb by David Grossman

Men in the Sun by Ghassan Kanafani

Returning to Haifa by Ghassan Kanafani

Wild Thorns by Sahar Khalifeh

Passage to the Plaza by Sahar Khalifeh

Apples from the Desert by Savyon Liebrecht

Time of White Horses by Ibrahim Nasrallah

A Tale of Love and Darkness by Amos Oz

Khirbet Khizeh by S. Yizhar

Poets

George Abraham

Zaina Alsous

Hala Alyan

Yehuda Amichai

Mahmoud Darwish

Suheir Hammad

Fady Joudah

Naomi Shihab Nye

Dahla Ravikovitch

Aharon Shabtai

Deema Shehabi

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

Ghassan Zaqtan

Fiction writers

Susan Abulhawa

Zaina Arafat

Orly Castel Bloom

Susan Muaddi Darraj

Randa Jarrar

Sayed Keshua

Etgar Keret

Sahar Mustafa

Dorit Rabinyan

Philip Metres

Philip Metres is the author of Ochre & Rust: New Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky (2023), Shrapnel Maps (2020), The Sound of Listening (2018), Sand Opera (2015), and other books. His work has garnered fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, Lannan Foundation, NEA, and the Ohio Arts Council. He has received the Hunt Prize, the Adrienne Rich Award, three Arab American Book Awards, the Lyric Poetry Prize, and the Cleveland Arts Prize. He is professor of English and director of the Peace, Justice, and Human Rights program at John Carroll University, and Core Faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts.