The myth of Herman Mankiewicz, passed down from generation to generation of his descendants, runs as follows: there once was a celebrated bon vivant in New York City, the “Voltaire of Central Park West,” a well-known member of the Algonquin Round Table, who, lured out to Hollywood by the promise of easy money, squandered his talent on screenplays for movies that were far beneath him, and soon drank himself into an early grave, hating himself for the weakness of not pursuing a higher calling. “I don’t know how it is,” he once said, “that you start doing something you don’t like, and one day you wake up and you’re an old man.”

But however simplified this myth is, or really, whether it’s true at all, it still begs the question: What of Herman before Hollywood? He didn’t move out to Hollywood until 1926, and he’d graduated from Columbia in 1917. A lot can happen in nine years.

So what happened? What was the shape of those first nine years of Herman’s professional adult life? Was there one? What had he hoped to be doing in the 1930s if not working as a screenwriter in Hollywood? Did he have a future mapped out for himself that he veered away from? Or was the whole thing one grand improvisation that went horribly wrong?

Of course, it’s not as if Herman knew, when this chapter of his life ended, that he was leaving New York for good, or even that the rest of his working life would be devoted to doing something for which he had little or no respect. So far as Herman was concerned, he was still doing it all, and living in California would just be a natural extension of the life he was building in New York—writing for the theater, contributing pieces to magazines, producing theatrical sketches, and living life as a famous wit.

But even above and beyond that, there was something else Herman was doing in those early years in New York, something that wouldn’t show up in the list of professional accomplishments, but something that meant more to Herman than he would ever admit, and explain the move to movies and California more than anything else. He was building a family.

To begin with, the round table was a hell of a lot bigger than Sara expected. Herman had told her about the people, of course, the intimidating names she read in columns and had heard so many stories about—Swope, Woollcott, F.P.A., Harpo Marx, Dorothy Parker, Benchley, Broun—but for some reason when she walked in, what she found most intimidating was the sheer size of the table, and the sense that came with it that she would be, as everyone was, on stage the whole time. The table must have been forty feet around, she guessed—and not only that, it looked lit by special lights. She wondered for a moment whether it was elevated, but no, she saw it was on the same level as all the other tables in the room; still, it definitely seemed set off from the rest, and not just by the velvet rope that she and Herman were ushered past as they walked in toward their seats.

This would not be a meal, she realized, but a performance. Or, more than that, a competition. Part sport, part art, with the wit sharpened to knifepoint, hovering for the kill. She would, she knew instantly, be completely mute until they left.

She settled into her chair, and the hour passed in a blur and panic. The Algonquin Round Table, by the time the former Sara Aaronson attended her one and only luncheon in the early 1920s, had become a New York Institution, a place where the leading writers, critics, and theater people of the day would gather to make each other laugh—and make a kind of news doing so. The wit and spontaneous jokes flew back and forth rapidly, though Sara couldn’t help feeling that much of it, though not really forced, was at least rehearsed. Spontaneous or not, though, the group and the gathering had become well-known as a center for sophistication and wit and creative brilliance.

But for Sara, once she got over her anxiety over even being there, the overwhelming impression was of its mean-spirited nature. As Clare Boothe Luce, who herself refused to attend more than a handful of times, put it, the lunches were “too competitive. You couldn’t say ‘Pass the salt’ without somebody trying to turn it into a pun or trying to top it.”

What horrified Sara most was the cruelty. In one instance, it was directed at one of the least extraordinary members of the group, a public relations man she knew only as Dave. She never knew the man’s last name, and he seemed a perfectly decent if somewhat plodding fellow, but for whatever reason the famed Algonquin wits seemed to have made a collective unspoken decision that afternoon to act as if he, Dave, were the funniest and most brilliant of them all. His simple request for the butter would be met with explosions of laughter, followed by, “Good God, did you hear what Dave just said?” and “Someone, for Chrissakes, write that down!” The man, Dave, was not beyond the understanding that he was being mocked, and took the whole thing in, Sara remembered, with a wan smile.

As for Herman, he was delighted to have finally persuaded his young wife to accompany him to the table, but he wasn’t particularly thrilled with the results. Sara was bright, intelligent, and actually had a great and direct wit. He wanted, she later thought, “to show me off so badly, wanted me to be funny. I wasn’t.” But while Herman may have been disappointed in his bride, he was, very clearly, absorbed in the maw, the give-and-take of the Algonquin Round Table—the barbs and wit flying back and forth had become second nature to him, and though Sara was too intimidated to even open her mouth (until the end—at which point, upon rising, her thanking them all for the honor caused yet another explosion of inexplicable laughter and applause from the whole company, which only underscored in her own mind the rightness of the decision to remain mute until then, and her subsequent decision never to return), she was pleased and invigorated to see Herman holding his own and leading the charge.

As she considered him, sitting there with a cigarette dangling from his lips, leaning forward into the table like a horseman riding low upon his mount, she swelled with pride. Yes, Herman had his faults, he was not a perfect husband, not by any stretch, but she’d known that for a while. As she looked at him, and saw him fending off barb after barb, saw the way the other men looked at him—they liked him and thought well of him, and like George S. Kaufman, who’d been his entrée into the New York world of wit and letters, they all seemed to respect his enormous gifts—she decided that she really should stop regretting her decision to marry him in the first place.

He never said, not once that anyone could recall, “I want to write” or “I want to be a writer.” Instead, the idea was to have written.Another legend in the family, or at least the one that Goma tried to propagate, was that her relationship with Herman had been nearly perfect—for all his flaws, he was, she insisted, a faithful, loving, devoted husband. And while it’s certainly true that he seemed to love her as much as he knew how, there’s also no question that their relationship improved dramatically after his death. Like many widows, in later years she emphasized the positive parts of her husband and ignored not only his own foibles and faults but the very real problems that she faced in her marriage. For the truth is that Herman, from the beginning, had been a handful.

They met in February 1918, when the young New Yorker went to Washington, DC, to report for the New York Chronicle on a speech called “A Panorama of Ancient Judaism.” While there, he caught the eye of a diminutive brown-eyed beauty; they were introduced by a mutual friend, and he walked her home that evening, talking of theater, politics, and the world. “I was absolutely in a dream world,” Sara said. “I had never heard anything like such talk.” Shulamith Sara Aaronson had grown up the second-oldest of five daughters and a single son to a Russian immigrant Reuben Aaronson and his wife Olga. Reuben was a Hebrew scholar who had taught math in Russia but who ended up owning a paper box factory when he moved to the United States.

Eventually, the business foundered—like her future husband, Sara’s father had no real business sense, but unlike Herman, he recognized the fault and did something about it: he took Sara out of high school so she could help run the business. Sara had long kept a list of her top beaus in the order of their current favor. After their first date (attending a musical comedy), she wrote Herman’s name at the top and drew an X through the rest. One of the things that appealed most to her, she later said, was that he was a young man in a hurry.

But it’s impossible to read or think deeply about the young Herman so intent on sweeping this young woman off her feet—“as if it’s a race,” Sara said more than once—without asking: What was he hurrying toward? Did he know?

After graduating from Columbia at the age of nineteen, Herman had joined the Army Air Service and gone off to aviation training school at Cornell, where he exhibited “zero flying aptitude,” becoming repeatedly and instantly airsick in flight simulators. With the war still raging in Europe, Herman had also kept corresponding with a girl he’d known while at Columbia, who he later said wrote him, “Go, my darling… go, and if need be, die.” After enlisting in the Marine Corps, Herman finally reached France as part of the 4th Brigade, 2nd Division, AEF on November 3, 1918. Thankfully, the armistice was only eight days away; Herman saw no fighting. In the months that followed, he ended up marching across northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg as part of a peacekeeping force. There, as he wrote back to Sara, he would entertain himself by telling the girls he met “fanciful lies about America, for example, that all American children are born with tortoise shell glasses.”

Returning from Europe in June 1919 to Quantico, Virginia, for demobilization, he went directly to Washington to see Sara. On only the third time they’d met, they took a trolley to Rock Creek Park and strolled around, Herman still in his military uniform. “He was so brawny and strong and wonderful,” Sara said, amazed but unconcerned by how much weight the wines of Europe had put on Herman. As soon as the two of them were alone in the park, Herman tried to kiss Sara, but she pushed him away, telling him that she would never kiss anyone unless she was going to marry him. Said Sara, “Honestly, I think I forced him to propose. I was just too pure for words.”

Meanwhile, Herman kept mulling over the problem of what to do with his life. His father was pressuring him to continue his studies, but Herman knew the halls of academia could never hold him. He had been bitten by the theater bug, and he was also fascinated by politics and journalism. And through it all his restlessness wouldn’t subside. Photographs of him taken in his early twenties show a young man with a sweaty hunger, an appetite for life that bordered on the gluttonous. He was sloppy, true, but young and voracious and eager, so eager to prove Franz wrong. His later claim “I’ll never live up to [Pop] and I’m not going to try” notwithstanding, Herman did try. He tried to work brilliantly. He tried to make a name for himself. He tried, with bluster and virtuosity, to gain his father’s approval by the sheer force of personality.

But there’s a curious aspect to Herman’s lifelong battle for Franz’s approval, especially after he returned from Europe. Unlike many, Herman wasn’t competing just against the standard his father had set down in his childhood. During much of Herman’s adult life, Franz was still an active presence. For all his judgment and criticisms of his sons, Franz was very much a part of their daily lives. To the end of his life, the old man was involved in Herman’s adult life—by Herman’s design. Whatever it was that he was getting from Pop—even when it was dismissal—Herman craved it.

The tragedy, of course, is that Franz was enormously proud of his first-born son. He crowed over his accomplishments, puffing his chest up, one friend recalled, as he told of Herman’s achievements at Columbia. He cared deeply about Herman, and his daughter-in-law came to rely on him for all kinds of advice. And later, when Herman and Joe were in Hollywood, succeeding in a field for which Franz had no feel and even less regard, Franz knew enough, Erna said, to be proud, and to brag about their accomplishments as best as he could understand them. One famous family tale, usually trotted out to show how unfeeling and mean Franz was, also speaks to some glimmer of pride in his sons: when they had films out in the cinemas, Franz, who of course had no time for the frivolity of movies, would pay his money to go in and watch.

He’d see one of their names in the opening credits—Written by Herman J. Mankiewicz, or Produced by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, or in the case of 1932’s Million Dollar Legs, Produced by Herman…, Written by Joseph… —two names! His sons!—and then leave the theater. He was satisfied that they were out in the world, making some kind of impact, even if it wasn’t one he would ever appreciate or understand.

Under such a thumb, Herman grew up with one real goal in mind and it wasn’t artistic satisfaction or mastery over his craft. No, what Herman wanted from the world was something it couldn’t possibly give: love. With such an impossible goal, his professional ambition was never to attain just success or awards or even acclaim; in fact, his precise ambition is challenging to trace, but revelatory. For instance, he never said, not once that anyone could recall, “I want to write” or “I want to be a writer.” Instead, the idea was to have written.

_________________________________________________________

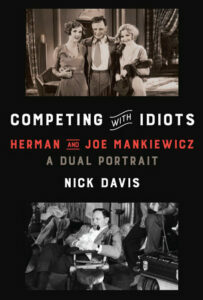

Excerpted from COMPETING WITH IDIOTS by Nick Davis. Copyright © 2021 by Nick Davis. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.