The Voice of the Sea Speaks to the Soul: On Kate Chopin’s The Awakening

An 1899 Review of Chopin’s Iconic Early Feminist Novel

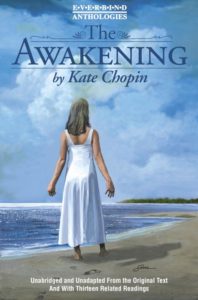

The voice of the sea is seductive; never ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring, inviting the soul to wander for a spell in abysses of solitude; to lose itself in mazes of inward contemplation. The voice of the sea speaks to the soul. The touch of the sea is sensuous, enfolding the body in its soft, close embrace.

*

“The Awakening by Kate Chopin is a story of the Creole life of New Orleans, by a writer who has already gained some reputation in picturing Louisiana scenes and characters. Her Bayou Folks was one of the most fascinating books lately written about a region full of possibilities to the maker of fiction. Her most recent book is more ambitious, being a novel, and evidently written with some sort of a purpose.

Just what the purpose is, the average reader will be puzzled to know; but it is quite evident that the book was not written for the Philistines. It is the story of a woman’s life, and whether or not it is a common story in any of its essential features, the public must decide. The heroine, Edna Pontellier, is an impulsive, passionate, and somewhat self-centered Southern girl, born in Kentucky, and married to a Creole whom she does not love.

“Like a great many other women, she has married when a mere girl, more because it seemed to be expected of her than for any other reason. At the age of twenty-eight, after becoming the mother of two children, she comes to understand herself, and, as is frequently the case, the agency of the ‘awakening’ is a man, Robert Le Brun, whom she suddenly discovers that she loves. He, on his part, recognizing the nature of the situation, abruptly leaves her and goes to Mexico.

And here comes in the part of the story which will seem inexplicable to most people: Edna, once awakened to the fact that she does not care for her husband, enters upon a violent flirtation with one of the roues of New Orleans. This comes to nothing; Robert returns, but leaves her once more, determined to save her from herself, whereupon she drowns herself. And that is the whole story.

“Whether the book was worth writing or not is a question which the public will settle. That it is well written is beyond doubt. It is the inner history of one of those women who, in modern days, figure in divorce suits; two centuries ago they would have figured in grim and horrible tragedies. It is a psychological dissection of such a woman’s soul; and most people will not understand it any more than they would understand the woman herself.

There are two other characters in the book who are admirably drawn in every way; the odd, quaint little musician, Mademoiselle Reisz, and the exquisitely feminine Madame Ratignolle. The portrait of Pontellier is also vivid, while that of Robert is slightly vague an outline. The book is an indication that the author may some day write a novel which will be an important addition to American literature.”