The adviser keeps a crystal bowl of lollipops at the end of her desk. She types C’s account number into the log as C sits and waits, purse in her lap, considering a flavor called banapple. She wants very much to select a lollipop, but it strikes her as antithetical to her goal of having her application approved. Impressions are everything, her mother used to say, and it seems to C that it is the defaulters who help themselves to pens and candies on the desk; everything gratis is tagged with hidden interest. Freedom is a credit score, a financial cushion, an investment in ETFs at mid-level risk pegged to a late retirement age. The adviser, who has ETFs and a broker herself, lets the stem of a lollipop bob unfairly in her mouth.

She removes the candy with a pop and rearranges her shawl over her button-down. So you can withdraw, she says of C’s IRA, the one her mother opened for her back when teenage C was also working at the supper club, ferrying classmates’ fathers’ plates of fish. Only you’ll have to pay the tax, okay?

C looks down at the notes she has taken on the complimentary stationery with a complimentary pen. She adds along the columns again, subtracts. There is satisfaction to be found in the fact that she has correctly accounted for the penalty. The right answer puts her at ease, as if the point of this exercise was to compute the correct solution rather than to generate a sum, any sum, in the actual world. Money is so wonderfully hypothetical—she’s hardly lifted a hand, and here it is, the IOU. No labor at all! Her work is done. She nods for the adviser to put in an order to liquidate what is left. So much for a balanced portfolio, which, for someone of her age, she’s learned should follow a moderate-risk and long-term ratio of 70/30 stocks to interest-bearing assets, with fractions in commodities, in gold. One should aim to have a third of one’s yearly income on hand at all times, ready to splurge. For emergencies like this, the adviser says.

The use of emergency still seems rather strong. C resents the suggestion that she has not planned ahead, spent prodigally, failed to save. As if one could put a bucket out in the rain to collect this emergency cash. The hysterectomy—now, that was an emergency. This is simply an unusual shift in circumstances, a dry spell, a blip. She’ll liquidate the Roth IRA—she’s a shopkeeper! the petite bourgeoisie! who among her kind ever retires?—to pay off the last two months’ bills, the hospital debts outstanding, and secure a small business loan for the coming year. She’s already canceled her health insurance. Screw penalties from the government. Maybe she’ll become a Republican—or a republican. Either way, she’s confident that this should close the gap. Her gaze rests on the candy bowl, flits from banapple to grape to orange.

Once she signs the loan, she’ll take the whole cornucopia home.

As we discussed, the adviser says, slipping the candy back into her mouth, this all gets easier once you find a guarantor.

*

She turns east on Pine, where the imperatives of a human microphone echo between the buildings. No drugs . . . No drugs . . . ! Or alcohol . . . ! Or alcohol . . . ! In this park . . . ! In this park . . . ! C takes the long way around. The temporary village makes her uncomfortable. There is too much moral authority in the Park; she suspects that they too resent her loans, or at least her efforts to repay them. The other day, when she took the route just past Zuccotti, she found herself surrounded by a set of clipboards, everyone pressing for her signature. C has learned the hard way the consequences of committing to the dotted line.

She pauses outside the slick face of a pecuniary institution. The ground floor is open to squatters and chess players and mothers with small children, a public space with potted palms and a little newsstand in a niche, where the candy bars are kept cool in the fridge. Upstairs, the bankers are up to whatever it is that C has never understood and now forgets. She stands smallish in their midst. It was all quite successful, really, if one viewed it as performance art—the banks had elbowed their way, rudely and in all-too-real terms, into the average person’s life. At least they’d created something of their own before destroying it. The face of the building shines obsidian, like a plaque. No one ever bothers to recount the end to that Arachne myth, C thinks, when the mortal outweaves Athena only to be permanently demoted to the status of an insect.

*

So. Why do you want to work in arts and crafts?

She conducts a number of interviews that afternoon, impressed by the chutzpah of her applicants. There is Shawn, Skyler, and a skateboarder whose name C immediately forgets. The conversations are brisk, petering out too quickly. I can’t paint, Skyler says. I know you teach classes.

She walks them through a typical day: restock, price check, update sale and clearance, lunch, midday sweep, lock up, erect the easels, teach. It takes so little time to describe her routine that when she finishes the applicants shuffle, snuff, and scratch, waiting for the other shoe, or shoes, to drop. They strike her as a twitchy bunch. Any questions? C asks to put them at ease. A woman named Breanna inquires abruptly about health benefits. C laughs. Sure thing. Top-notch plans! They even cover lobotomies, she’s tempted to add.

One by one, the job seekers leave, saying they hope to hear from her soon. C watches them disappear through the prow of the store. Yes, soon, she agrees. She doesn’t know what else to say; she isn’t quite sure what she’s hiring for, this hypothetical employee she cannot afford. They are mostly art students, and while she regrets stringing them along, she more resents them for imagining that she’s in a position to help, that she’s any better off. She pauses by the bins of alphabet beads and looks into the street, thinking of reasons to hire Yi. It was Yi, after all, who came up with the idea for the painting class. She’s always wanted the shop to succeed. If only Yi had more money, no mortgage, perhaps she might act as guarantor—

Uh, miss?

The most recent contestant sends a hand through his heavily gelled hair.

I was just saying I haven’t worked in retail before.

The door chimes. The applicant exits and another man enters in a wrinkled T-shirt, Army-issued khakis sagging on his doughy hips. He has a shape like a softened cereal box. She turns to tell him she’s sorry, there aren’t any jobs here after all, vacate the premises, but it’s clear he’s not interested in employment. He hikes the khakis up as he orients himself, makes his way from the row of abacuses to a rack of neon poster boards. He selects a sheet, brings it to the register, and plucks a marker from the pitcher as he asks, Hey, can I borrow this?

C watches as he scrawls YOU. SHAT. THE. BED., then rings him up for a dollar and change.

He disappears through the front windows and down the street, a flash of pink that dissolves into the gray scale of the suits. She has to admit: the look suits him. She considers her own neon ad, glowing brightly in the window. Fuck you too, she thinks.

*

At six on the dot, she turns the sign on the door from open to closed and sets up the children’s easels. Soon, four small girls arrive. They cling to their mothers’ hands, clutch shyly at tall, slim thighs, until the women peel them away and kiss them goodbye. The easels stand in the prow of the store, stacks of beads shoved aside. A mother arrives last minute to enroll her son. He’s very talented, she pleads. C detects shadows around her eyes. They have no idea how desperate she is. There are no policies, no plans. The boy sulks by the drawing pads, covertly bends a corner. On the spot, C invents a midcourse registration fee.

The theme of the class is advanced landscapes and natural scenery, and the children tear through the material at an alarming speed. C is mildly concerned they will run out of things to paint. To draw out the curriculum last week, she introduced ideas of perspective and vanishing points, an exercise that elicited not only the steady horizon lines she had hoped the lesson would produce, but also entirely derivative experiments; the girls were always looking for new ways to break the rules. So far they’ve covered trees, mountains, shrubbery, gardens, and magnificent sunsets that stuff up the ends of city blocks like fauvist fatbergs—and, of course, flowers. Today, they will learn to paint the sea.

Pots of gray and shades of blue stand on the center table. C shows her pupils how to mix the white into this base. They add texture to the wave, simulating the spray and foam. The carousel projector is balanced atop the cash register, and C turns off the lights. Images appear on the opposite wall.

Thirty-six ways of looking at Mount Fuji, and they consider only one: the tsunami reaches with its icy talons for three small boats rowing into the slope of the wave, into the shadow of the crest, certain to be demolished. The imminence of the sailors’ deaths strikes her as perhaps inappropriate for children of this age. For them, death is something factory-farmed and shrink-wrapped into Styrofoam trays. No beaks, no eyes, no guts, no claws: totally defanged. They just aren’t prepared.

One of the girls raises her arms menacingly over the child next to her. I drowned you, the first one says. You’re dead.

The canvases are already filling with roses and petal shapes. Someone breaks into the paint cabinet and removes a pink. C has marketed the class as a painting program for the gifted. Let your children expand their imaginations! Statistically speaking, there aren’t enough gifted children to go around. Demand exceeds supply. C fills in the gap. She moves from easel to easel, trying to encourage the little prodigies to employ their brushes in the style of Hokusai. Look, she says, pointing at the projection. The wave is like a monster. Look at the long talons of the wave! She needs at least one success to remind the mothers of the value of forking over the cash on which C’s business model currently depends. The little boy is the only one capable of focus. He is quiet, shy; he ignores the others’ billows of blooms. He looks intently at the projected print, then at his canvas, and this seriousness alone is enough to win C’s forgiveness of his poor treatment of her sketch pads. He smashes his brush into the navy-blue. When C comes to admire his easel, she sees he has recreated the wave in astonishing likeness, as well as four little easels and four little girls, standing in its path.

__________________________________

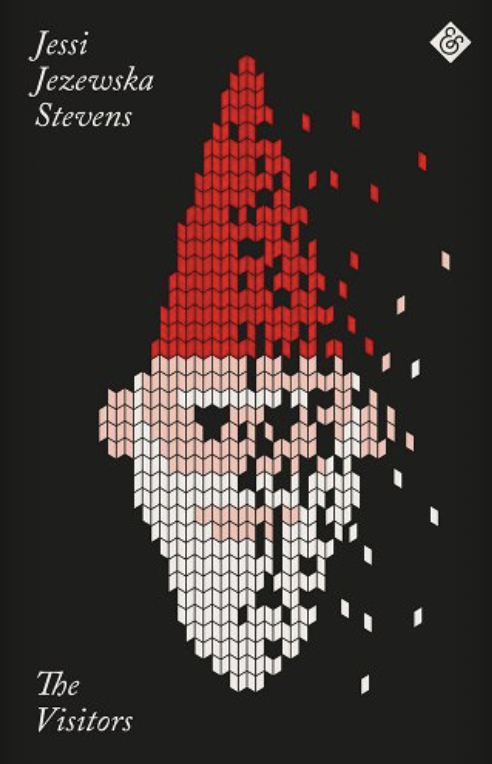

From The Visitors by Jessi Jezewska Stevens. Used with permission of the publisher, And Other Stories. Copyright 2022 by Jessi Jezewska Stevens.