In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth.

Maartens wrote at a time when the semicolon was still an exceptionally popular punctuation mark—so popular that grammarians forecast the extinction of the colon, which 19th-century writers had abandoned in favor of semicolons. “The colon is now so seldom used by good writers,” an 1843 grammar pronounced, “that rules for its use are unnecessary.”

Not everyone was so sanguine about the trendy semicolon shouldering colons off the page; one of the 19th-century’s most accomplished grammarians, Goold Brown, tried to rescue the colon by urging writers that their beloved semicolons depended on the colon for sense. “But who cannot perceive,” begged Brown, “that without the colon, the semicolon becomes an absurdity? It can no longer be the semicolon, unless the half can remain when the whole is taken away!” Colons simply weren’t “fashionable” anymore, he groused.

Nowadays, however, it’s the semicolon that is no longer a la mode; and judging by the number of writers who have something like an allergic reaction to it, plenty of people might find a glimmer of truth in Maartens’s vision of the semicolon as disease vector. “Let me be plain,” wrote the novelist Donald Barthelme: “the semi-colon is ugly, ugly as a tick on a dog’s belly, I pinch them out of my prose.”

Bill Walsh, a long time copy editor at the Washington Post, affirmed that the semicolon was indeed “an ugly bastard.” Semicolons are “idiocy,” Cormac McCarthy scoffed in a Vanity Fair interview. Kurt Vonnegut and Gertrude Stein dismissed them as pretentious; George Orwell was comparatively kind when he labeled the semicolon “an unnecessary stop.” Is it any wonder so many people are afraid to venture a semicolon when even the pros shun them?

The grammar rule books bending our bookshelves aren’t helping much either; a look at their history shows that they’ve usually made writers feel less certain about grammar rather than more so: the more rules there are, the more potential pitfalls there are, and the more confusing “exceptions” astute readers note in the prose of great English stylists.

The semicolon’s fall from favor was determined in part by the contradictions, complications, overcompleteness, and incompleteness of rule books. But if we look past those books to the work of some of our best writers, we can see semicolons used to create music and meaning in language that no other punctuation mark could accomplish.

Thoughtful punctuating is an occasion to stop, reflect, and immerse ourselves in the contemplative art of the well-judged pause.

Raymond Chandler is famous for his noir detective novels featuring Philip Marlowe, but he was a brilliant essayist as well, and the semicolon seems to have been one of his favorite punctuation marks. He used it to create expressive rhythm in his writing, in ways that leapfrog rules. Consider this sentence from his essay “Oscar Night in Hollywood,” in which Chandler contends that too few people appreciate film as an art form:

They insist upon judging it by the picture they saw last week or yesterday; which is even more absurd (in view of the sheer quantity of production) than to judge literature by last week’s bestsellers, or the dramatic art by even the best of the current Broadway hits.

The part of that sentence that lies beyond the semicolon can’t stand on its own as a sentence, and a rule book would tell you that you should therefore use a comma rather than a semicolon where Chandler has. But listen to the cadence that Chandler has orchestrated. The initial clause, representing filmgoers’ mulishness, is short, simple, restrained, quiet; and then comes Chandler’s indictment of their “absurdity,” loud, crisp, and abrupt, thundering past the complaints of moviegoers. Lose that extra pause provided by the semicolon and you also lose the persuasive force and Chandlerian flavor of the sentence. These moments of rule-chucking in his writing are not accidents: “When I split an infinitive,” he railed to the editor of his film essay, “God damn it, I split it so it will stay split.”

What Chandler and other excellent writers knew is that a book of grammar rules is incapable of answering the question of how, and how often, to use a semicolon, because the answer is a matter of what you, the writer, are trying to accomplish. No matter what you’ve read in a book or been told by an English teacher, for instance, a sentence can’t be too short or too long in an absolute sense. A sentence can be too short or too long to suit its purpose.

Perhaps the best use of the semicolon I’ve ever read is in a sentence that’s 318 words long—just under a third of the length of this entire essay. That sentence is in Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and if you look up the letter, you’ll know exactly which sentence I mean when you get to it. King is describing why he is unwilling to continue to wait for change without taking action, and to make his point strongly felt, he makes you wait in pauseless discomfort while he recounts injustice after injustice, all semicoloned together one after another, never letting you rest on a full stop. Read it out loud and you’ll be exhausted and breathless: justly so.

If rules aren’t the key to mastering the semicolon—if they can’t tell us how to be truly effective writers—how can we, too, deputize semicolons to get our points across like Chandler and King? “It takes time,” Rebecca Solnit, another skilled semicoloner, says candidly in “How to Be a Writer.” Chandler and King were so deft with their punctuation because they invested time and attention in reading other good writers, and they poured just as much time and attention into crafting their own sentences.

That sounds like a lot of work, I know, especially when many of us were taught from an early age that grammar is a logical, rigid, and memorizable science. Alas, to punctuate well requires deliberation. But perhaps that’s a good thing. According to the CDC, mindfulness-based practices like yoga and meditation rose significantly between 2012 and 2017. Venture capital firms have poured millions into apps like Calm and Headspace. If we all scanned our emails, texts, Tweets, reviews, and essays, looking for opportunities to use something a little more interesting than the now ubiquitous, catchall em-dash, we might find that thoughtful punctuating is an occasion to stop, reflect, and immerse ourselves in the contemplative art of the well-judged pause, with no monthly subscription required.

In Maartens’s The Healers, Professor Lisse eventually discovers that the semicolon isn’t a toxin as he initially believed; instead, when formulated properly, it’s a source of vitality. We modern writers, with a little bit of observation, thoughtfulness, and playful experimentation, might come to see it that way too.

__________________________________

Excerpt adapted from Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark. Used with the permission of the publisher, Ecco. Copyright © 2019 by Cecelia Watson.

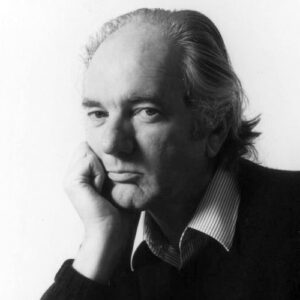

Cecelia Watson

Cecelia Watson is a historian and philosopher of science, and a teacher of writing and the humanities. She is currently on Bard College’s Faculty in Language and Thinking. Previously she was an American Council of Learned Societies New Faculty Fellow at Yale University, where she was also a fellow of the Whitney Center for the Humanities and was jointly appointed in the humanities and philosophy departments.