Throughout the writing of my book about the murder of Patrick Karegeya, I kept thinking about the Epimenides paradox. The one that runs: “‘All Cretans are liars,’ says Epimenides, the Cretan.” It came to mind because Rwandans kept telling me that deceiving others, being economical with the truth, was something their community reveled in, positively prided itself upon.

Especially when dealing with Western outsiders. A proof of superiority, not shame, when successfully achieved. So much so, that the practice had worked itself into the language. Naïf comme les blancs (Naive as the white folk), Rwandans will say of someone, in the same way that other cultures will say “as thick as two short planks,” or “as dumb as a post.”

One of Rwanda’s prime ministers, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, shocked the head of a UN peacekeeping force by telling him: “Rwandans are liars and it is a part of their culture. From childhood they are taught to not tell the truth, especially if it can hurt them.” She was one of the first victims of the 1994 genocide, murdered by interahamwe thugs.

A successor told me the same thing over coffee in a Brussels hotel lobby many years later: “In Rwanda, lying is an art form. When you, as a white journalist, leave a meeting, they will be congratulating themselves: ‘We took her for a ride.’ Lying is the rule, rather than the exception.”

It was an accusation tossed into conversations with Tutsis and Hutus, Rwandans and Ugandans, diplomats and military men, lawyers, and journalists. “You spoke to so-and-so? Oh, he’s the most terrible liar.”

It was not, it seemed, a recent practice. Dip into the history and you quickly stumble upon gleeful deceits. One is the story of German explorer and naturalist Dr. Richard Kandt, who arrived at the gates of the Rwandan royal court in 1898. When Dr. Kandt asked to see the Mwami, King Yuhi Musinga, the courtiers did what they always did when presumptuous white men ventured into this land of misty volcanos and rolling green hills: they presented him with a kinsman and awaited his reaction, laughing among themselves at the German’s anticipated stupidity.

Dr. Kandt, however, had not only bothered to learn the local language, he had done some research. He knew that the Mwami was a teenager. Expressions changed as he shifted into Kinyarwanda, pointing out that this fully grown “Mwami” must be a fake and asking to see the real king. His eventual reward was to be made Resident in Rwanda, a mediator between the Rwandan Tutsi court and a renascent Germany hungry for an African empire. His house in Kigali is now a national museum, a fitting tribute to one of the first westerners to beat a Rwandan at his own game.

English adventurer Ewart Grogan, a contemporary of Kandt’s, after an 1899 trip to “Ruanda-Urundi,” as it was then known, railed bitterly against the mendacity of local guides, who would deny the existence of a mountain, he claimed, even when it virtually stared him in the face. “Lies, lies, lies, I was sick to death of them,” he wrote. “Of all the liars in Africa, I believe the people of Ruanda are by far the most thorough.”

It’s not surprising, perhaps, that historically, dissimulation and secrecy became prized in an incestuous court beset with intrigue, where nobles lived in constant fear for their lives. Ritualists relayed messages from a Supreme Being only they could decipher, earthly power rested with a Queen Mother who sat invisible behind a screen, and the aristocracy exerted feudal dominion over the peasantry, obliging each hamlet to spy on its own inhabitants and report back to the throne.

Around the personage of the Mwami, who was never publicly seen to eat or drink, swirled a haze of euphemistic terminology. “The King is seated” indicated he was performing bodily functions; “The King has given his person” was the closest a courtier came to indicating the Mwami might have died. To be elliptical, layered, intellectually opaque—these were signs of good breeding. The crudeness of direct speech was reserved for peasants.

Kinyarwanda itself is a language infused with subtle wisps of meaning, hidden references its intended audience immediately picks up but foreigners miss. “Oh, if only you spoke Kinyarwanda you’d understand, it’s as clear as day,” a Rwandan will often exclaim in frustration, after translating a politician’s content-packed speech, which, when converted into English, appears, disappointingly, to say nothing terribly significant. To the Rwandan’s ears, the threats are direct, the promises crystal clear.

Kinyarwanda itself is a language infused with subtle wisps of meaning.

Look up the word ubwenge in a Kinyarwanda dictionary and the translation reads “wisdom,” or “sense.” But it can also be translated as “cunning,” “deception,” a quality Rwandan children are encouraged to develop, seen as the ultimate sign of maturity. It goes hand in hand with the concept of intwari, which French historian Gérard Prunier defines as “the quality of impassivity, aloofness, being beyond and above events, implacable.”

Intwari was expected of young Tutsi boys destined to become warriors. Dignity before spontaneity: “In this respect,” adds Prunier, “the culture the Rwandans most resemble are the Japanese.” But what he is describing also echoes the “stiff upper lip” made famous by English aristocrats, a characteristic associated in both countries with an upper class groomed from birth for leadership and military service in defense of the nation.

As a Rwandan psychologist once told me: “To show emotional reserve is considered a sign of high standing. You do not just pour out your heart in Rwanda. You do not cry. It’s the opposite of Western oversharing, a form of stoicism.”

A culture that glories in its impenetrability, that sees virtue in misleading: to someone proposing to write a nonfiction account embracing many of the most controversial episodes in Rwandan history, it posed a bit of a challenge.

Two deadly secrets squat at the base of Rwanda’s modern history: the circumstances in which the charismatic commander of the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) met his end in 1990; and the question of who shot down the plane carrying the Rwandan president and his Burundian counterpart, a double presidential assassination that set the 1994 genocide in motion. Few contemporary histories are so thoroughly contested. With the passage of the years, a variety of analysts, commissions of inquiry, and investigating magistrates have changed their minds on key points, angrily contradicted one another, or simply given up on the attempt to establish the truth, opting for a bland: “No one will ever know.”

The conflicting narratives would be understandable if the events in question dated back thousands of years. The fact that they concern episodes that took place in the last quarter of a century, involving players often still available for interview, highlights the problem posed by the calculated unreliability of key witnesses.

When it came to embroidering the truth, Patrick Karegeya, Rwanda’s former head of external intelligence, knew more than most. During one of our most intriguing conversations, he explained some of the characteristics of the political lie. We’d been talking about Muammar Gaddafi, whom Patrick (almost everyone referred to him by his first name) had met several times. For decades, African rebel groups routinely turned to the Libyan leader for arms and funding—and he often obliged. Like many despots, Patrick said, Gaddafi possessed an elephantine memory for faces and names. “He was like a library, he knew everything about Africa, about every African leader. He was not good at analysis, but he knew everything about everyone.”

I mentioned that both Mobutu Sese Seko and Haile Selassie possessed similar memories: contemporaries and biographers remarked upon it. What explained that prodigious retention of detail?

“Because he had evil intentions,” was Patrick’s simple answer. “When you are lying, you focus on the lie you are telling, because you know you need to remember it when you next meet that person. You remember the encounter, because you were lying all that time. Whereas if I try in a year’s time to remember this coffee with you, I won’t be able to recall when exactly it took place or what we said or did. Because I was just being myself.” Deceit, if it is to be sustained, requires focus.

It was said with rueful self-knowledge. In his latter years, Patrick—like many of those interviewed for my book about his murder—was trying to undo a knot of his own tying. He and his closest colleagues in the RPF were responsible for a compelling narrative peddled to journalists, diplomats, human rights workers, Western officials, and ordinary Rwandans throughout the 1990s and aughts. They had sold that story with passionate energy, driving aggression, and a sophisticated understanding of their respective audiences’ guilt complexes and pressure points.

These were men supremely skilled at seduction, intellectual, emotional, or sexual. American diplomats weary of negotiating with sleazy Great Lakes politicians thrilled at the puritanism of these thin, driven young men in camouflage. NGO workers who were new to Africa’s Great Lakes listened to their tales, hearts pounding with sympathy and outrage—initially, at least. Reporters, photographers, and filmmakers became lifelong friends or ended up jumping into bed with them. Intensity, along with imminent danger—and the Great Lakes has always been a dangerous place to live and work—is one of the great aphrodisiacs.

These were men supremely skilled at seduction, intellectual, emotional, or sexual.

One journalist I know, working for a mainstream news agency, covertly joined the RPF’s intelligence payroll; another confessed, many years later, to carrying a top-secret message for the movement to a Congolese minister in Kinshasa: the conflict of interest this represented never crossed his mind. After the genocide, Rwanda could so easily be viewed through the prism of the Holocaust and the pledge of “Never Again.” And to the Anglo-Saxon world, at least, it seemed clear who the Good Guys were: the insurgent RPF.

It was a storyline that required careful curation by officials like Patrick, and the history of the period is littered with deliberately leaked memos, suppressed reports, and many a daring forgery. The men I spoke to went on to challenge and undermine the account, only to discover—irony of ironies—that they had done their original work rather too well. Having superbly marketed the narrative of the underdog turned moral crusader returning home, they found, when they tried denouncing it, that their listeners preferred the lie to its teller. When Cretan Epimenides tells you not to believe the Cretans, why would a sane person listen?

The debate over the Rwandan narrative has always been polarized between those—often Francophones—who saw the RPF as invaders willing to sacrifice millions in their ruthless quest to return Tutsis to power in Rwanda, and those—usually Anglophones—who saw them as warrior-liberators who, tracing a giant geographical and historical boomerang, overturned one of Africa’s most evil regimes.

The level of hatred and contempt felt by each side for the other is astonishing. Perhaps only the Israel-Palestine debate can equal it for venom. The vitriol is in part explained by the stakes involved, the extraordinary amount of blood shed at every stage. Who can contemplate all those hundreds of thousands of dead—not just in Rwanda, but in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)—and remain coolheaded?

As Paul Kagame gradually emerged as one of Africa’s uncontestable autocrats, damning evidence kept surfacing of RPF atrocities. At first it could be brushed aside, using the classic justifications of realpolitik: Rwanda was situated in a rough neighborhood, the argument went; its government, trying to restore peace and security to a traumatized society, could not be held to the standards of Sweden or Switzerland.

Then the movement that had seemed to outsiders so united began splintering, and key members quit and ran. The RPF’s self-imposed oath of Omertà, rigidly observed up till then, began to crack, and as it did so, people like me who had seen the RPF as implacable, certainly, but a disciplined, highly effective movement with a farsighted leadership and a progressive agenda, felt our certainties begin to tremble.

As examples of RPF human rights abuses and unaccountability accumulated, I was not the only previously supportive journalist who winced, frowned, and was quietly grateful to be writing about other things. My career had taken me elsewhere, Rwanda was no longer my beat. Still, it was painful to accept that I might have unwittingly misled my readers.

When Cretan Epimenides tells you not to believe the Cretans, why would a sane person listen?

On the few occasions when I met up with Patrick Karegeya during these years, I avoided asking him certain questions. Of course, I kick myself for that now. I told myself it was out of politeness. Reminding an exiled spy chief that he had once told the media the exact opposite of what he was now saying seemed, well, rude. The guy was down on his luck, beleaguered in every sense of the word, why rub salt into his wounds? But my concern was also for myself: I didn’t want to confront the truth of just how thoroughly I might have got it wrong.

Political philosopher Frantz Fanon captured that disinclination perfectly: “Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn’t fit in with the core belief.”

The greater the effort that goes into forming a belief, the more reluctant those who hold it are to adjust their lenses. The investment a shamefaced outside world poured into Rwanda after the genocide—financial, emotional, intellectual—was enormous, given the country’s tiny size and population. No wonder so many are reluctant to reassess.

What I discovered, however, was that whatever the conscious mind decides to engage with—or bypass—one’s cognitive process continues to churn heedlessly along in the background. There came a day when, with a near-audible mental ping, I realized I no longer believed most of the key “truths” upon which the RPF had built its account, and hadn’t for ages. It felt like a relief. Shibboleths can weigh heavy on the soul.

One thing I never doubted, not for a second, was that a genocide had occurred in Rwanda in April 1994. I’d seen the bodies, gagged at the unmistakable aroma that comes off a hurriedly buried mass grave, registered the bloody handprints left on the walls of classrooms and church buildings by Tutsi men, women, and children scrabbling to escape their executioners. Images of that kind are hard to forget.

What I no longer believed was the RPF’s explanation of how the country had come to reach that terrible point, or the movement’s depiction of itself as not just a morally blameless actor during the buildup to that episode, but the rebel equivalent of a knight in shining armor, cantering in to lance the dragon of ethnic slaughter.

__________________________________

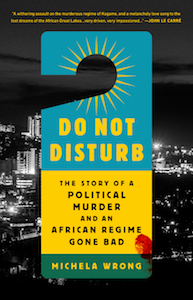

Excerpted from Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad. Used with the permission of the publisher, PublicAffairs, an imprint of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2021 by Michela Wrong.