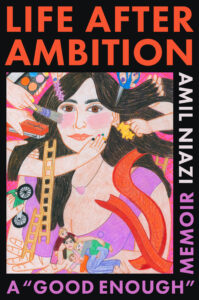

The Ups and Downs of “Having it All”—and Why It’s Okay to Give it Up

Amil Niazi on Motherhood, Watching Bosch, and Taking Risks

My ambition had taken me from Toronto to London five months postpartum with my first child, working as a digital commissioner at the broadcaster’s headquarters in Oxford Circus. A place I had idolized since childhood. It was everything I thought I had ever wanted, when I thought being a journalist was as much as I was allowed to want, the culmination of decades of graft, grit, and sacrifice. At the same time I was caring for a child, and every single notion I had about myself was crumbling. My previous desires and drive slipping through my fingers like my son’s neon-colored slime.

I was helping to commission digital content for the factual entertainment department—they made the nature docs and saccharine baking shows, but I felt unsure about what we were supposed to be doing. I struggled with not getting too involved in the creative direction of projects being brought to us, still seeing myself as being on the other side of the table, the one with the ideas, not the one with the power. My boss always told me, “We’re not the creatives.”

To take a risk like that had always felt indulgent and impossible.

I was there to bring other people’s visions to life. I felt my ideas were, at best, ignored; at worst, scoffed at. I wondered if, in an effort to get somewhere better, I’d given up everything that was good in my professional life, the work I actually loved doing.

I wanted to write, but I never wanted to go back to those days at the magazine, starving and scrounging and so desperately worried about how I’d eat or pay the rent. I’d yet to see a model of creative success I could emulate, where someone like me was able to do what I wanted to do. To take a risk like that had always felt indulgent and impossible.

By September, Matt had found work too, and we got a spot for Sommerset in a day care near our flat. I’d imagined I’d conduct a rigorous search for childcare, looking for a place that practiced the Montessori style and would feed my precious baby only the best organic food.

Instead, I was chucking him into a nursery that satisfied the basics of being near a train station and having an open spot. I kept getting strep throat from the day care germs. I usually did drop-off and pickup because of Matt’s commute, and every single day the baby bawled his eyes out when I left him. At first the day care workers and even my boss said, “Just give it two weeks.” Two weeks went by, then a month went by, and two years later, he was still crying.

I had the kindness to at least wait until I’d left the nursery to have my own cry, wondering when I’d gone from “she can have it all,” to “she’s having a nervous breakdown.” After work, I usually only made it to the staircase of our apartment building before whipping off my shirt and giving the baby what he’d been screaming for the whole walk home. Then we’d make dinner—some kind of barely edible ready-meal from M&S—play with the baby, and put him to sleep.

I started to feel like a punishing daily commute and an eight-hour emailing marathon weren’t worth the sacrifices.

And then we’d watch Bosch.

The only thing keeping me grounded was the idea that I could still do something meaningful, where my real self and my work self were connected instead of splintered, one constantly hiding from the other. I blame TV in general for convincing a very impressionable young me that my work, and by extension my life, required a very specific arc, something to reach for that would readily signal to others that I’d achieved accomplishment and success. That new moms don’t leak at work, that precious breastmilk never gets spilled in the nursing room.

I desperately envied the creatives I was commissioning, and they envied my proximity to power, my ability to reject or empower them. The whole enterprise felt like a losing game. I started to feel like a punishing daily commute and an eight-hour emailing marathon weren’t worth the sacrifices.

It all felt a bit like dying.

I didn’t know what I wanted. Should I try leaning further into the job we’d uprooted our entire lives for? My fantasy of what I was supposed to do and be was colliding hard with the reality of who I had slowly become after the baby.

It had already been a year of killing myself and I felt like I had less than I started with. Part of me also yearned for another baby, to have more of the joy that being with Sommerset was bringing me. It didn’t feel impossible. Lots of women at work were coming and going from maternity leaves, though one had come back early and talked to me about a new breast pump she’d found that you can wear in your bra and pump right at your desk. She said it like I should be excited about the prospect, but I just thought about how the darkened pumping room had been my daily meditation, a chance to be alone. I wasn’t sure I wanted to give that up so I could soothe my engorged breasts at my desk, beside my boss and a kindly woman who always asked me how I was but never listened to the answer.

I asked to work from home on Fridays so I could stay home with S one day a week. On days I had little work, it was lovely. When I had to take care of a toddler and answer emails and take calls from my boss, it was like my brain was on fire. I felt in those moments that I was deeply failing at both conceits.

I was examining the sacrifices I had made on either side and questioned why the balance seemed so off. Maybe I’d gotten everything I was supposed to want, but I wasn’t getting to experience any of it fully. I was a whisper at work, a ghost at home.

The worse I felt, the better Bosch made me feel.

I became a zealot for the show, telling everyone how much they had to watch it, only to feel insane when I started to describe the premise and realized I was pitching something far more personal and vulnerable than a corny detective show. One day my boss came in and said she’d put the show on and had to turn it off. She looked at me askew after that. As my job became increasingly tedious, I started asking myself why I was sticking it out at something that was making me so miserable that I’d started obsessively dedicating my precious time off to an Amazon Prime show for dads. Bizarre as it seemed, Bosch’s passion and singular focus had unearthed my own desire to get closer to the thing that gave me a sense of purpose, to actually pursue my own passion.

I’d only ever felt that way when I was writing, but I was terrified to do it because I’d never had a way to afford to pursue a creative career. But as S grew and the demands on my time became more intense and more at odds, I felt far more selfish and protective of where that time was spent.

Bosch and the baby had shone a mirror on all the parts of myself I’d been denying for so many years as I sought to climb higher up the career ladder, but further away from myself.

I also started obsessing over my own mortality. Ever since S was born, the idea of my own death had come sharply into focus. I kept thinking about how his world was just unfurling, while mine was starting to shrink. Might as well make the most of it while I still could, I started to think.

*

After months of agonizing over whether to stay or leave, what it would mean for where we lived, or how we’d live, I decided to take a tentative step off the ledge I’d been standing on.

One Sunday, Matt and I were walking with S along Regent’s Canal near our flat. We’d moved here because of my fixation on where I thought I “needed” to be, rather than where I was, and now I was going to turn to him and tell him that I was wrong. I wanted to quit my job. I had to quit my job. I’d negotiated some freelance contracts working with production companies that would pay well while I started pitching my own articles and essays, wading back into the writing world.

He told me to go for it. He’d have my back.

I already knew that without his support, I couldn’t or wouldn’t do it. It would put extra pressure on him and alter our household income. And all this as we’d started fertility treatments for another baby.

There is a world in which I stopped with Sommer and went on to have a lucrative and exciting career doing whatever that version of myself would have done.

Only, I didn’t want “less baby or even less work,” I told him. In fact, I wanted more of both, but not in the way I’d been doing either.

Matt had always been the practical one, the one who kept the train on the tracks. I was sure he’d be upset about my sudden turn. I’d been working up the courage to tell him what I wanted the whole walk, teeing up the words and then instantly pulling them back, terrified to name what had been eating at me the past year and a half.

We stopped so I could feed the baby and, sitting there, bathed in the fuzzy light of a London spring, I finally said out loud, “I’m quitting.” I didn’t dare look at him, fearful of his reaction.

Eventually I said why, about how life and death and baby and Bosch had all come crashing down on me over the past couple of years, and after being flattened by all four, what was left was the screaming desire to be completely and utterly myself in my work, to find the purpose that was so clearly missing in what I did, what I had been doing for so long.

That meant finally writing, not as a hobby or a side hustle, but as the thing that propelled me forward. When I finally turned to face him, I could see immediately that none of my fears about his support or lack of support were real. He’d watched me struggle over the years to fit myself into the narrow boxes so many of my old jobs demanded, how unhappy I still seemed to be, despite how much I’d thought I’d wanted this. He told me to go for it. He’d have my back.

We watched the houseboats on the canal bouncing gently along the water, an occasional arm popping out a small, round window with an empty wine bottle.

Relief and anxiety and love and excitement and panic all washed over me as we sat watching Sommer play.

__________________________________

Copyright © 2026 by Amil Niazi. From Life After Ambition by Amil Niazi, published by One Signal/Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Amil Niazi

Amil Niazi is a writer and producer. She writes The Cut’s series on parenting, The Hard Part, and covers work and motherhood and how the two intersect. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post.