The Unsung Woman Who Changed How We Take Care of Newborns

How Virginia Apgar Revolutionized the Metrics for Measuring a Baby's Health

Ingenuity was never far from the surface in Virginia Apgar’s life and the newborn screening test that carries her name, the Apgar test, was equally ingenious in its simplicity and effectiveness.

As Virginia developed her interest and skill in anesthetics between 1939 and 1949, she was drawn to its applications in obstetric medicine. According to Dr. Selma Calmes, a leading anesthetist, Virginia entered this field “in the right time and the right place.” It was not common in the 1940s to be anesthetized when giving birth, but Virginia’s new job involved her in the process of Caesarean delivery. This did require anesthetic, the application of which was not well understood—in its effect on either the mother or the baby—and resulted in unacceptably high maternal mortality during or just after birth.

Virginia’s flexibility and openness to new developments—which extended to her own ability to admit mistakes when they occurred—were instrumental in moving the discipline of anesthetics forward. New anesthetics were being developed and Virginia made numerous careful observations of how they affected both the mother and the newborn baby. Between 1949 and 1952, she gathered data on the early moments of a newborn’s life, health, and prognoses.

Virginia’s powers of clinical observation and her ability to make important changes in obstetric anesthetics, and disseminate that knowledge, did not go unnoticed. One of her colleagues, Dr. Stanley James, later said, “Virginia was not just a doctor. She was also an educator.” As obstetric anesthetics was such a new field, there was not much published material but Virginia was pragmatic by nature and improvised with what teaching aids were available: she used old bones, or even her own pelvic bone which had an unusual shape, shocking one Australian doctor who had heard about Dr. Apgar’s pelvis and presumed it belonged to the old and much used skeleton.

The feature of delivery rooms that struck Virginia so forcibly in the late 1940s and early 1950s was the care of babies just after they were born. The focus was more on the mother’s wellbeing than the baby’s. Hospital deliveries were replacing home births, which meant that more mothers and babies were surviving the birth process, but the first 24 hours of a baby’s life were still an uncertain time.

The medical student may have been surprised by the seemingly instantaneous production of a new scoring system, but Virginia’s thoughts were the result of her many years of painstaking observations and clinical knowledge.

There was no routine examination of the newborns’ vital signs and, if there was, the methods varied from hospital to hospital and were often unscientific, and even unsafe. Doctors were missing signs that a baby was, for example, starved of oxygen, a factor in half of newborn deaths. Some doctors assumed that babies that were underweight or struggling to breathe should be left to die. “It was considered better not to be aggressive. You dried them, you shook them and some doctors patted them on the backside and that was it,” said Professor Alan Fleischman, professor of pediatrics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

There was a dire need for a system that checked vital signs, such as heartbeat and breathing rate, from the minute a baby was born. That way, the appropriate special care could be put into place before it was too late.

Virginia’s eureka moment occurred one morning while she was having breakfast in the hospital canteen. One of her medical students asked her how to evaluate newborn babies’ wellbeing. Virginia replied, “That’s easy. You would do it like this,” and jotted down the five vital signs to look for. Initially called the Newborn Screening System, it was the first version of what became the Apgar test.

The medical student may have been surprised by the seemingly instantaneous production of a new scoring system, but Virginia’s thoughts were the result of her many years of painstaking observations and clinical knowledge. As a practicing anesthetist, Virginia’s daily work involved close contact with newborns. She had seen seemingly healthy babies being whisked away from their mothers to be weighed and measured, only to turn blue and struggle to breathe.

Virginia understood the importance of checking the five vital signs at one minute after birth. Each of these is given a score of zero, one, or two. A total score of seven to ten is considered normal, while four to six necessitates some intervention to stimulate, for example breathing, and a score below three leads to emergency treatment. Few babies get a perfect ten one minute after birth, as the circulation—oxygenated blood—often hasn’t reached the fingers and toes fully, so these can still be blue.

This is a rare example of a universally accepted and applauded test that was quickly and routinely applied.

As the Apgar score became more widely used, it was clear that having a second set of measurements would reveal how the baby was thriving after being born. Comparisons between scores taken at different times would enable the healthcare professionals to monitor improvement or deterioration. Now, the Apgar test is routinely performed at one and five minutes after birth. If necessary, it can be repeated at ten minutes.

After testing the scoring system on more than 1,000 newborns, Virginia’s test was presented at a meeting in 1952 and, in 1953, Virginia published her findings. The sole-author publication, in Current Researches in Anesthesia and Analgesia, detailed the score’s value as a predictor of newborn survival. This is a rare example of a universally accepted and applauded test that was quickly and routinely applied. On the back of the wave of optimism following the advent of antibiotics, the world of medicine was ready for new advances.

Ten years later, in 1963, the newborn screening test was officially designated the Apgar test, when Dr. Joseph Butterfield at the Children’s Hospital in Denver suggested an acronym using Virginia’s surname to help users remember what to look for: Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, and Respiration. When he wrote to Virginia about it, she replied, “I chortled aloud when I saw the epigram. It is very clever and certainly original.” Dr. Joseph Butterfield published this acronym in the Journal of the American Medical Association:

• A is for Appearance. A normal pink skin color all over scores two. If the color is normal on the body but blue on the feet and/or hands, the score is one. A blue or very pale body is zero.

• P is for Pulse. A newborn baby’s pulse (heart rate) should be over 100 beats per minute, denoting a score of two. Less than 100 beats per minute is one. If the pulse is absent, the score is zero.

• G is for Grimace. This tests for reflexes after stimulating the soles of a baby’s feet. If a tickle or gentle slap elicits a jerking movement of the legs or a cough/sneeze, the score is two. A grimace scores one and no reaction zero.

• A is for Activity. Muscle tone is indicated by free and regular movement of the arms and legs, scoring two. If the arms or legs are flexed, the score is one. Lack of movement scores zero.

• R is for Respiration. If the baby cries and is breathing well after birth, this scores two. If the breathing is slow or labored, the score is one. Absence of breathing is zero.

________________________________________

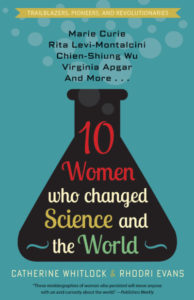

Excerpted from Ten Women Who Changed Science and the World by Dr. Catherine Whitlock and Dr. Rhodri Evans. Copyright © 2019. Available from Diversion Books.

Dr. Catherine Whitlock and Dr. Rhodri Evans

Having gained a Diploma in Science Communication from Birkbeck College, University of London—as well as a PhD in Immunology—Catherine Whitlock now works as a freelance writer. She has written for numerous magazines and websites including The Wellcome Trust and Nature Publishing Group. She is a Chartered Biologist and a member of the British Society for Immunology and the Association of British Science Writers. She lives in Kent with her husband and three children.

Dr. Rhodri Evans studied Physics at Imperial College London, before gaining his PhD in Astrophysics from Cardiff University. He has taught at a number of universities around the world and is the author of numerous popular-science articles. He speaks regularly at conferences and is a regular contributor to the BBC on Physics and Astronomy. His popular blog can be found at The Curious Astronomer.