The Unlikely Pulp Fiction Illustrations of Edward Hopper

When the Iconic Painter Drew Cowboys for Adventure Magazine

In the winter of 1956, Alexander Eliot, art critic for Time magazine, interviewed Edward Hopper for a cover feature on the painter’s roundabout path to fame. Intended to familiarize general audiences with the man behind classic paintings like Nighthawks and Early Sunday Morning, the resultant profile reads today like a paean to an American master. Eliot was taken with Hopper’s “unalterable reserve.” Presenting the artist as a frugal and unsentimental old man who often conflated self-effacement and self-flagellation, he painted his own portrait of a folksy messiah—a humble savant capable of rescuing American realism from a clique of “clattering egos.”

Given this messianic tilt, it’s not surprising that as Eliot broached Hopper’s early days as a commercial artist, he referred to the period as his “time in the desert.” For the first 25 years of his career, Eliot related, Hopper had failed to support himself solely on his painting and therefore paid his bills drawing covers and interior art for publications like Hotel Management, Everybody’s Magazine, and the Wells Fargo Messenger. Eliot spun this existence into a retroactive tragedy. Advertising firms and publishing houses had wanted America’s greatest living realist to “draw storybook characters posturing and grimacing.” Hopper had simply wanted to “paint sunlight on the side of a house.”

From the July 1919 issue of Everybody’s Magazine.

From the July 1919 issue of Everybody’s Magazine.

To Eliot’s credit, 60 years later, art historians still struggle to reconcile the most sensational of Hopper’s commercial illustrations with the quiescent scenes that earned him a place among the great 20th-century artists. Hopper biographer Gail Levin described this squaring-up process in 1979; while many of the artist’s commissioned illustrations allowed him to perfect subjects “in which he was especially prolific”—offices, ships, railroads, hotels, and restaurant scenes—several forced him to confront unfamiliar and at times uncomfortable themes.

“Art historians still struggle to reconcile the most sensational of Hopper’s commercial illustrations with the quiescent scenes that earned him a place among the great 20th-century artists.”

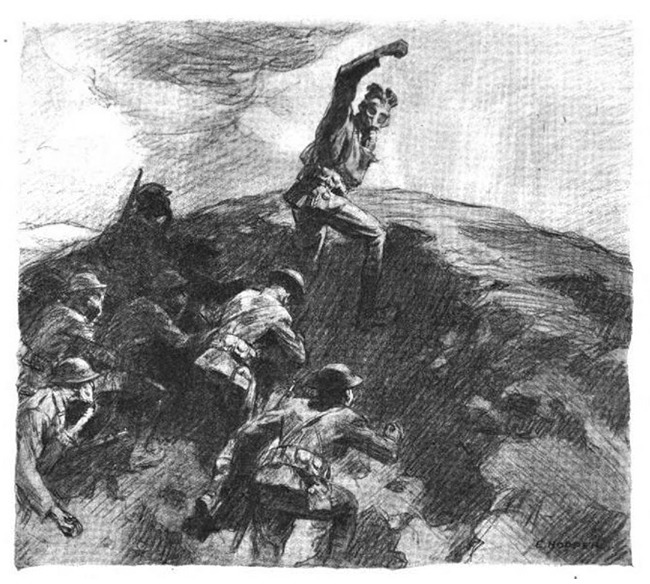

Nowhere was this more evident than in his work for the pulp-fiction magazine Adventure.

Between March 1916 and March 1919, Hopper illustrated five issues for the publication. In these magazines, the famed realist—a man whose plaintive portraits and landscapes now sell for tens of millions of dollars—drew heading art for stories like “The Sourdough Twins’ Last Clean-Up,” “Snuffy and the Monster,” and “A Fish Story About Love.” Hopper enlivened these stories with images that ranged from amusing to maudlin. One illustration, perched above Holda Sears’ “The Finish,” shows an explorer in a life-and-death struggle with a man-sized python. Another, atop Hapsburg Liebe’s “Alias John Doe,” depicts two cowboys “tabletopping” a patsy—one of his subjects kneeling behind their victim while the other topples him over. Additional pictures portray rampaging apes, spear-wielding natives, and pioneers wearing coonskin caps.

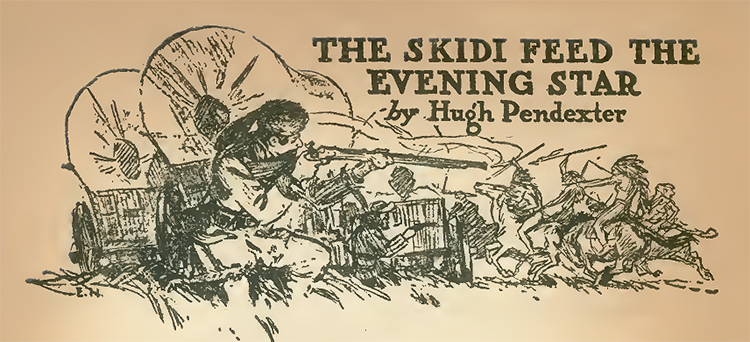

From the July 18th, 1918 issue of Adventure.

From the July 18th, 1918 issue of Adventure.

According to pulp-fiction historian Richard Bleiler, such diverse subject matter was typical of a catch-all mentality that made Adventure—the first issue of which hit newsstands in October 1910—one of the most successful of the early pulps. Though later competitors succeeded by specializing in specific genres, Adventure thrived by harboring a catholic mentality, which focused on wide-ranging stories about treasure hunters, espionage, crime, and exploration. From the start, readers responded to this approach. “Adventure had enormous newsstand sales as well as many subscribers,” Bleiler says. “The magazine had sufficient funds that it could do such things as issue identification cards for its fans and even sponsor an expedition to Abyssinia [modern day Ethiopia].”

Hopper’s work for the magazine came during its halcyon days under the stewardship of editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman. Far from an arriviste, Hoffman was, by the time he signed Hopper’s paychecks, a well-connected and well-respected editor. His acquaintances at the time included novelists Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis, the latter of whom also worked at Adventure between 1911 and 1913. According to Bleiler, Hoffman’s demanding standards set his magazine apart from other pulps.

From the July 18th, 1918 issue of Adventure.

From the July 18th, 1918 issue of Adventure.

“A writer had to write well and know whereof she or he wrote,” he says. “This sounds silly and self-obvious, and today perhaps it is, but this was not always the case. Hoffman’s Adventure showed that literary sensationalism did not have to involve pandering or cliché writing.”

To Hopper, of course, none of this mattered. During this period, he took only as much illustrating work as needed, and he seems not to have differentiated Adventure from other paying magazines like Farmer’s Wife, Country Gentlemen, or even Scribner’s. According to Carter Foster, deputy director for curatorial affairs at the Blanton Museum of Art and author of the book Hopper Drawing, Hopper despised illustrating no matter the client. “He took the work seriously insofar as he was a great artist and could certainly do it well,” Foster says. “But he didn’t like other people telling him what to draw or paint—he liked to come up with his own subjects.”

As Levin wrote in 1979, Hopper’s attitude toward illustrating was “the antithesis of that of popular illustrator Norman Rockwell.” He never aimed to elevate illustration to a high-brow artform, nor did he view the work as anything more than a paycheck. Hopper himself described this mindset to Eliot in 1956. As a freelancer, he recalled, he often dropped by unannounced at a publication’s office with a portfolio tucked beneath his arm. “Sometimes I’d walk around the block a couple of times before I’d go in,” Hopper said, “wanting the job for money and at the same time hoping to hell I wouldn’t get the lousy thing.”

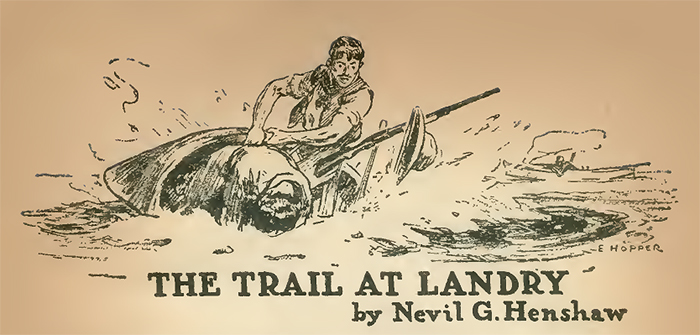

From the March 3rd, 1919 issue of Adventure.

From the March 3rd, 1919 issue of Adventure.

As to what Hopper’s illustrations for stories like “The Roughneck,” “The Two-Gun Girl,” and “The Dance of the Golden Gods” contribute to his greater legacy, Foster believes they demonstrate how his talent bled through even when restricted by house style guides. Though Hopper did not put the same level of effort into these drawings as he did other artwork, he “was a keen observer of human emotion and behavior, and this can certainly come through in his illustrations.”

More importantly, Foster argues, the critical tendency to identify incongruity between his illustration work and the realism for which he is now known is itself misguided. “His work is closer to surrealism or magic realism,” he says. “Although he carefully observed the world to get material for his art, he always molded and changed this to create his own subjective vision.”

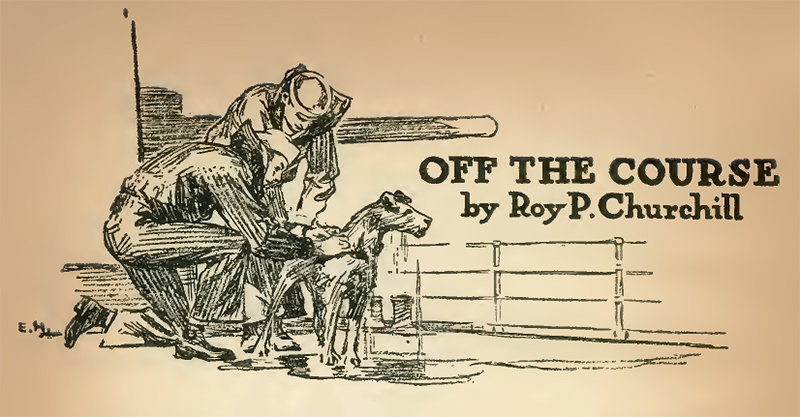

From the July 18th, 1918 issue of Adventure.

From the July 18th, 1918 issue of Adventure.

Luckily for Hopper, a sold out 1924 watercolor show soon freed him to explore this vision without financial restraint. Though he still sold an occasional illustration over the next three years, he never again relied on the trade for a living. The further he removed himself from this work, the more reluctant he grew to talk about it, and, by the time he spoke to Eliot in 1956, his attitude toward illustration had fully hardened into regret and resentment. Evidence suggests, however, that this was not always the case.

In 1979, Levin discovered an article Hopper published in the April 1927 edition of The Arts. Written about the career of his old friend, John Sloan, the essay, according to Levin, reflected a tacit acknowledgment from Hopper that his own years as an illustrator had played a significant role in his growth as an artist.

“Hopper saw virtue in Sloan’s illustrations where he found only shame in his own.”

“John Sloan’s development,” he wrote, “has followed the common lot of the painter who through necessity starts his career as a draughtsman and illustrator: First the hard grind and the acquiring of sufficient technical skill to make a living, the work at self-expression in spare time, and finally the complete emancipation from the daily job when recognition comes. This hard early training has given to Sloan a facility and a power of invention that the pure painter seldom achieves.”

Hopper, then, saw virtue in Sloan’s illustrations where he found only shame in his own—a double-standard modern scholars fortunately refuse to replicate. While most still view his Adventure illustrations as aberrational, few deny that his work for less sensational publications like Hotel Management, Tavern Topics, and the Wells Fargo Messenger allowed him to indulge and refine his chief curiosities. There, he captured women perched before sewing machines, families dining in Chinese restaurants, sailboats struggling in the wind. To Levin, this thematic sinew without question affixes Hopper’s illustrations to his greater oeuvre despite any late-in-life self-abnegation.

“What he was not so willing to admit was that in his work as an illustrator there are glimpses of the direction his art would take in the future,” she wrote. “The embryonic Hopper who would become one of America’s most outstanding realists is present in the illustrations even though he resisted total involvement in them.”

Daniel Crown

Daniel Crown is a freelance journalist based in New York City. His work has appeared at the Washington Post, Gizmodo, Vice, Atlas Obscura, the Awl, and several other publications.