The Unique Pleasures of Letter-Writing in a Era of Impulsive Interaction

Jackie Polzin on the Focused, Private Connections of

Good Correspondence

During the first month of the pandemic I was afraid to write to my grandpa. I imagined the virus, bright pink but invisible, smearing the paper and the envelope and the mail carrier’s glove, and so on, all the way to my grandpa’s hand. In April I began sending him a weekly letter at the nursing home where he lives in St. Peter, Minnesota. I had previously written him twice a year, as thanks for the twenty dollars he never fails to send on my birthday and on the anniversary of my wedding day. He’s ninety-five years old. He has five children and twelve grandchildren and seven great grandchildren, and has not had a visitor in his apartment for more than a year.

When I was growing up, writing letters had not yet gone out of fashion. Our fourth-grade class conducted a letter exchange with kids in Japan. My sister, twelve years old, was assigned a soldier in the Gulf War as pen pal. I often sent letters to a cousin with the unvaried closing BCF (Best Cousins Forever). Through my high school years my mother wrote letters to an ailing man in South Dakota whose replies were written in such shaky penmanship it became a family pastime to sit around the kitchen table deciphering his words. This was also the heyday of the chain letter: a pyramid scheme made entirely of letters. If it all worked out, you became rich… in letters. It never worked out. (I once received a response from my grandma explaining she wouldn’t be taking part, on principle, and she was sorry if she ruined my chain.)

A precise feeling of fondness accompanies the receipt of a letter from someone you care about. There are as many shades of this feeling as friends in the world.Even so, my life has been full of letters. The woman who had granted me a fine arts scholarship at the end of high school sent autobiographical poems, and always alongside her signature was an ink stamp of a giraffe. When I studied abroad in Ireland, I received news of karaoke and misadventure from college friends via airmail to my chilly shared flat. During the six months I stayed in Cork I also received so many letters from Polzins, the year 2000 remains the most well-documented period in the history of my family.

Every time I moved, I gained pen pals. Upon leaving New York City, a chef I had worked with sent letters that, without fail, referenced Lucinda Williams, and once included a recipe for mango pie. I first learned one friend was an artist when I moved away and her letters that followed bore strikingly detailed pencil drawings. Throughout a boyfriend’s semester in Holland, I filled a shoebox with his letters, and he filled an Albert Heijn grocery bag with mine.

A precise feeling of fondness accompanies the receipt of a letter from someone you care about. There are as many shades of this feeling as friends in the world. Yet I sometimes leave a letter unopened for days, not knowing if I am ready to read it. A friend I still write to confessed the same thing. I wonder what we think those sealed letters contain.

I recently happened across “a few loose rules for being a good correspondent” in a memoir by Louise Dickinson Rich. The book, We Took To The Woods, published in 1942, is an account of self-imposed exile in the woods of Maine. In the winter Rich walked more than a mile each way over deep snowpack in skis or snowshoes to collect the mail from the post at Middle Dam.

When you write a letter, Rich asserts, you are thinking only of the person who is going to receive it. She recommends keeping notes of what you might include. I do this now: traffic stopped by a fox on Charlton; mouse trap under the oak tree in Harmon Park; L found a dragonfly wing—“it doesn’t need a body to fly!” The notes remind me that writing a letter is a way of taking notice of the world around you and your thinking about the world.

Rich warns against writing too long a letter or answering too promptly, both of which make responding a burden. She suggests never expecting a letter back, so as to be “delightfully surprised” if you receive one. Or, as has been my experience, you might receive your own letters returned to sender: a letter to the wrong address; every letter to the boyfriend abroad, left behind in a closet empty of his things; my own letters as inheritance from a pen pal who died in her nineties. It is unsettling to read these relics of my thinking, containing ideas I no longer identify with and emotions displaced by time. (I was surprised to find that my love letters seemed almost generic, i.e., classic pining.) Confronting my outdated words has helped me to accept the complex nature of putting thoughts down on paper. Thinking is transient. And filtered. And flawed.

So often these days we interact on impulse, intent on sharing with as many people as possible. Writing a letter is focused and private. Letters take time to write. As with any kind of writing, sitting down to do it is the hardest part. I’ve put off writing letters for months, years even, and then addressed the envelope first, setting into motion what had, for so long, seemed too difficult.

Once I begin, I’m surprised by how quickly I can write a letter. My secret, if I have one, is to not start over after writing a few lines. I cross out a lot of words. I’ve come to appreciate the inked-out portions as proof that it’s difficult to say what you mean, a realization that can make us all more forgiving of saying the wrong thing.

Since quarantine began I’ve visited my grandpa twice, speaking to him on the phone from outside as he sat in his third-floor apartment, his face unreadable behind the window screen. My family and I have blown giant bubbles as he watched, drawn a prominent rainbow on the sidewalk nearby, flown a kite, which prompted him to say he never had all this stuff as a kid—he built roads out of sand and drove his toy car on them until the roads fell apart. I’m comforted by this image of my grandpa as a boy, making his own fun.

He has thanked me for the letters at every opportunity, responds at intervals, and often adds in closing that I shouldn’t feel I have to continue writing them. But a letter can be there when I can’t. Our letters are a closeness we can keep.

When I miss my grandpa I have a ready stash of the letters he has sent me over the years (often accompanied by newspaper clippings), to Madison, to Ireland, to New York City and Boise and St. Paul. I study the carefully printed words and I imagine him standing there, silver pen in his shirt pocket, gesturing the way he does when he talks. A finger held aloft to summon a worthy point, or the chopping motion he makes with the edge of one flat hand on the palm of the other, marking his words. With his letter in my hands, it’s easy to believe he is thinking of me, too.

__________________________________________________

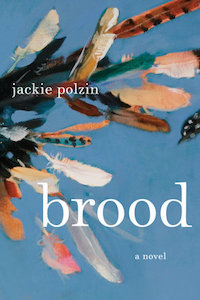

Jackie Polzin’s Brood is available now via Doubleday.