The Unglamorous Life of an Editorial Assistant Struggling with Her Mother’s Mental Deterioration

Liz Scheier on Romance Novels and Furious Phone Calls

The year I was born, Jackie Kennedy Onassis was working as an editor at Doubleday. I like to imagine that she sat down at a formidable dark-wood desk every morning, crisply dressed, and worked her way through manuscripts in silence, marking them up with a blue pencil, and that every afternoon at five pm her assistant knocked on her office door bearing a glass of perfectly chilled chardonnay.

Publishing was no longer quite so glamorous by the time I showed up. Neither, in fairness, was I.

I had interned at the merged Bantam Doubleday Dell in high school. I worked for a subsidiary rights coordinator and spent most of my time editing down cover copy into smaller and simpler segments, suitable for non-native English-speaking agents and scouts, for the rights guide. Twice a week after my last class ended, I took the subway to Times Square, hunkered down in an unused storeroom qua office, and typed happily away.

I was really in it for the book room: a bedroom-sized storage closet, crammed with metal shelving set in narrow aisles, with extra copies of books jammed in every which way. “Take whatever you want from there,” said my frazzled supervisor as she rushed by. She didn’t have to tell me twice. BDD published genre fiction, and piles of it. I stocked up on my beloved science fiction, piles of paperbacks with gleaming robots and ringed planets crowding the covers.

I piled up new fiction in hardcover—Hardcover! Unimaginable luxury!—and squirreled everything away in my bedroom. The next year, I passed that internship along to my camp friend Arie with tips on which managers to ask for interesting work, and painstakingly described directions from the elevator to the book room. No fool he, he came prepared with an empty backpack.

I got my first job out of college at Bantam Dell, which had just cut off Doubleday as a stand-alone imprint, on a different floor of the same building. We shared the building with BMG, and every now and then as you passed the cargo entrance, a giant garage door would roll up and a limousine would glide smoothly out. Once, I caught a glimpse of Michael Jackson’s drained face and tousled hair as the window rolled up. We loved those celebrity sightings but thought of them as taking place in another world; as entertainment went, books were the slim-margin, grubby, ink-stained stepchild to the real work of the building.

I worked for a gorgeous, energetic romance editor named Kara, only a few years older than I was. She’d picked me out of a pile of equally eager, equally unqualified bright-eyed, bushytailed English majors because “I saw you used to work in a bar, and I figured you’d be fun.” We quickly became friends and went out to author lunches and book parties as often as I could convince her to take me along. Her mother, a fierce, tiny Italian woman from Scranton, would call multiple times a day with questions and commentary; once, I had to stick my burning face into Kara’s office and say, “Listen, I’m sorry, but she’s asking—I would never ask otherwise but—OK, I’m just going to say it—your mom is in Banana Republic and wants to know what pants size you wear.”

“Oh my Goooooood,” she groaned. “Just transfer the call.”

I knew it would be years before I was allowed to acquire any books of my own, and I was perfectly happy just being in proximity to books, typing up marketing plans, writing rejection letters, sending authors flowers on publication day. Once a month, the company ordered all the assistants pizza and we sat in a conference room for Slush Lunch, a beloved tradition where we opened all the unsolicited submissions we’d received from hopeful authors who hadn’t managed to snag the attention of a literary agent. Most were just terrible, but there were enough doozies—prison mail (so much prison mail!), synopses scrawled in crayon, tinfoil-hat conspiracy theories, occasionally packaged in actual tinfoil—to keep us in material.

Romance writers like to have industry people speak at their conferences. Savvily, the southern chapters of the Romance Writers of America hold theirs in February. I made far too little money to take a proper vacation, but I spent many weeks in those first few winters holed up in janky Holiday Inn conference rooms during the day trying to look older than I was, and carousing drunkenly in the hotel pool at night with whatever assistant literary agent they’d brought down. The luxury of staying in a hotel—A hotel! In my own room!—just floored me. I shared a three-bedroom in Astoria with two beloved friends from summer camp, and I was grateful for the quiet.

Leaving for parts south also gave me some breathing room from my mother’s increasingly frenzied calling. I didn’t have a cell phone yet, and when I traveled I felt the lighthearted, childish glee of playing hooky; I was beyond where she could reach me. She raged upon every return—why hadn’t I given her the number of the conference organizer or hotel security, what was wrong with me—but I was finally beginning to fully accept that her demands were bizarre and that I wasn’t the problem. The boulder was off my chest. I still listened to the voice mails, tears of atavistic fear rushing to my eyes when she screamed, but I could also choose not to return them.

The fear wasn’t entirely unwarranted. Something was changing with her. She was losing what little filter she’d had. My mother ran on pure vengeance, and age—hers or mine—hadn’t slowed her down. When we fought, she would show up in the lobby of my office building, threatening security until they called me down. How a small woman with a heavy Queens accent managed to bully large, burly men into compliance, I don’t know. But she did it. I would go down just to keep her from screaming the doors off. The last thing I needed was for my publisher to pass by and notice a resemblance. Far better to hustle her out the chrome revolving door, muttering apologies just to shut her up. I despaired of ever being fully out from under her thumb.

One spring evening, I was standing in a supermarket aisle debating the relative merits of two shapes of pasta when my brand-new Razr flip phone rang. I wedged it between my shoulder and ear. “Hello?”

The other end of the line was silent, and then there was a sniffle. Then a keen. “Elizabeth…” Her voice trailed off. I groaned inwardly. It was Tranquilizer Voice.

“Hi, Mom. What’s wrong?”

Another sniff. “Oh… you know. This is a hard time of year for me. I miss my mother, Elizabeth.” Her mother was forty years dead, but every spring the grief came back as fresh as the first.

“I know, Mom. I’m sorry.”

“I think she must be lonely, all by herself down there in her grave. Don’t you think she must be lonely?”

I paused with the winning box of penne suspended above my basket. This was new.

“I. I mean. I don’t think her soul is still there, Mom. I’m sorry, I know this is hard, but she’s not in there anymore, you know? It’s just her body.”

That was a mistake. She wailed anew, and a woman walking by looked over her shoulder. I grimaced apologetically and turned toward the shelf with my shoulders hunched.

“Are you OK?”

“Well!” She seemed to gather herself. “I have an idea, Elizabeth. I think I know how we can fix this.”

I did not like the sound of that “we.”

“I know you don’t want children. I know you don’t. But, listen—hear me out. You could have a stillborn baby, right? You could do that.”

I boggled, silently.

“And then—you see, this is brilliant! We could put the baby down in the grave with her, and she wouldn’t be lonely. They would both have company. And everything would be alright.” A beat passed, and she said, more gaily: “Well, just think about it. Think about it. Call me back.”

She hung up, and I stared around the store with bugged-out eyes as other people went about their shopping, blissfully untroubled by the image of an arthritic elderly woman digging up her mother’s grave by moonlight, a small bundle tucked under one arm.

I went home and opened a bottle of wine and watched Buffy the Vampire Slayer and tried to pretend that Joyce Summers was my mom. As coping mechanisms go, I highly recommend this. As she got older, I liked to half-joke—gallows humor being a helpful crutch—that it was getting harder and harder to identify if any given act of shittiness was her dementia, her eccentricity, or just her being a garden-variety asshole. She had never had a firm hand on her temper, and with age she no longer seemed to even try to manage it, screaming red-faced at the slightest conversational hiccup. She also started to lose track of what she had done and when.

An obsessively careful record-keeper and the source of my habit of paying bills immediately when they arrived, she forgot to pay a $14 AmEx bill. When the next bill came with a late payment fee, she called the bank screaming furiously—How dare they, didn’t they know her history as a stellar, upstanding customer?—and refused to pay the bill at all. The next month came with another fee, with a percentage of the whole charged as a penalty, and she threw it in a drawer. The next month came, and then the next. The bill rose more than a thousand dollars over that $14, and the credit card company called me, the rep’s voice unctuous and faux-concerned—Didn’t I want to pay her debt for her? Wasn’t it the right thing to do?

I hung up on them.

Against the terms of her lease, she housed Columbia grad students and young office workers in the apartment’s two extra bedrooms. They weren’t allowed to have guests, and had to put up with her peculiarities, but for nominal rent in a twenty-four-hour doorman building half a block from Central Park, they paid up without a peep. Many of them were international students hungry for a connection of any kind, and years later, I am still in touch with many of them: the woman from East Germany who told me stories of life behind the Berlin Wall, her family of four sharing their four allotted bananas per year, grateful her father didn’t like them so they could split his; the gay Argentine man who found New York much more libertine than Córdoba; the teacher from Istanbul who wrote to me in horror every time he saw a parallel between Trump and Erdoğan (he wrote often).

Something was changing with her. She was losing what little filter she’d had. My mother ran on pure vengeance, and age—hers or mine—hadn’t slowed her down.

The bright side of her ever-slipping control was that she started telling me things she hadn’t meant to. Most of them meant nothing: the names of men she’d dated in high school, trips she’d planned on taking. One afternoon she insisted on taking me out to lunch, and we sat at a sidewalk table outside a sushi restaurant. She puffed furiously while thumbing the menu. I had taken to buying her cartons of Marlboros from dubiously legal websites at cut-rate prices; the packages arrived weeks later stamped with customs marks from former Eastern Bloc countries. I hated being her supplier, but also knew things went better for me when she had nicotine to keep her calm.

“Ma’am,” said the meek waitress, “I’m so sorry, but you can’t smoke out–”

Mom turned her most terrifying gaze on her; the blue-steel barely-contained-rage glance over the bifocals. “Young lady,” she bit out, “I have been smoking since before your mother failed to shut her legs for your father. And I don’t intend to stop now. I want the tempura. Elizabeth?”

She pointed her menu at me. “Sushilunchspecialthankyou,” I rushed out. Mom took my menu, slapped it together with hers, and handed the two over. The waitress caught my eye, and I mouthed I am so, so sorry as she backed away, shaking her head.

“Get her,” Mom said cheerfully. “Telling me to stop smoking. Oh! I’m seeing that hypnotist again, though. He’s helped me quit before.”

“A hypnotist?” I said. “Like, with a pocket watch and a waistcoat?”

“No, no,” she laughed, shaking her head. “He’s a psychologist. You remember, I was seeing that David Kagan, but he gave up! He told me he couldn’t do any more for me. Borderline isn’t curable, he says. I think he’s just lazy.”

“Wait, what isn’t curable?” Her eyes flashed and she drew herself up.

“Nothing. You mind your own business, Elizabeth. No one asked you.”

__________________________________________________________

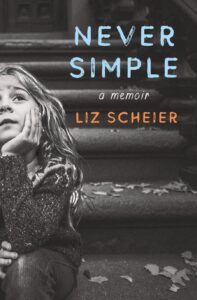

Excerpted from Never Simple: A Memoir by Liz Scheier. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2022 by Scheier, LLC. All rights reserved.

Liz Scheier

Liz Scheier is a former Penguin Random House editor who worked in publishing and content development for many years, including at Barnes & Noble.com and Amazon. She writes book reviews and feature articles for Publishers Weekly. She is now a product developer living in Washington, D.C., with her husband, two small children, and an ill-behaved cat. Never Simple is her first book.