She realizes that her mother and father are the only people who got dressed up. Her father is wearing a camel-hair topcoat over his suit. He’s skipped the tie—but she has no doubt it’s in his pocket, just in case. Her mother is wearing a red coat over a pair of nice slacks. That’s what she calls them, “slacks”; it’s always “slacks” unless she’s going riding, and then they are “dungarees.” Neither is dressed in a way that would keep them warm if they had to wait outside. Everyone else is wearing regular clothes: hats, gloves, parkas over long pants. Her own coat bears the symbol of an upscale company on the upper arm. A while ago she put a piece of dark duct tape over it, hoping perhaps that people wouldn’t notice.

“Today’s the day,” someone says.

“The moment is now,” another man adds.

“Picked out your turkey for Thanksgiving yet?” her father asks one of the men. She notices that he’s guiding the small talk away from the events at hand and toward more generic seasonal chat.

“No, sir,” the man says. “This year I’m going to visit my brother up by Seattle.”

“Fine man you are.” It’s charming how pleased her father is to be among these men and women.

He’s beaming; his excitement is palpable. He shakes hands, any hand he can get hold of. “You have to touch people; you have to look them in the eye and listen to what they have to tell you,” he’s said to her in the past.

“You don’t like it but you have to listen. We used to have a word for it—decency.”

“Nice to see you,” her mother says to one of the women. As they move around the room, both her mother and father greet strangers as though they’ve met them before.

“Good of you to come out,” a man calls out to them.

When she was younger, going places with her parents used to make her feel special; people paid extra attention; she imagined herself as a princess. When she stops to think about it now, she’s embarrassed.

Her father moves with a kind of swagger, occupying space in a way that might make you think he is the candidate. But he’s not; he’s the machine that makes it go—the money.

“Bull in a china shop,” her mother once said when she was angry with him, and then she got defensive when Meghan looked shocked. “Well, you don’t get rich being mister nice guy,” her mother said and left it at that.

“They’ll be coming,” she hears someone say. “Just before lunch, and then again at the end of the day.”

“People are gonna show up for sure; that’s what they do when they have something to say.”

“Some folks feel it’s already been said,” another one adds.

“Either way, it shouldn’t be optional,” one of the men says. “It should be legally required; if you’re of age, you’re required. That’s just my opinion, but no one gives a hoot what I think.”

“Folks don’t like to be told what to do.”

“You’d think they’d want as many people as possible to participate,” another man says.

“A little naïve,” her father whispers. “It’s always interesting to hear how common people see it.”

“Why do you say ‘common people’?” she asks.

He looks confused. “What should I say?”

“Just people?” she says. “When you say ‘common people,’ it sounds like you see yourself as different from everyone else.”

“I am different,” he says. “I’m rich and proud of it. Common people should be glad to see me and be happy when I buy their products and eat in their restaurants; it’s a sign of approval.”

“Whose approval?”

“My approval.”

“And because you’re rich, your approval means more than someone else’s?”

“If you were studying for a test, would you take advice from an A student or a C student?” he asks.

“Is this a test?”

“It’s life,” he says.

“It makes people feel bad, like they’re less than equal,” she says.

“It’s not my job to make people feel equal.”

“Are teachers less valuable than doctors? They get paid less; but without teachers, you wouldn’t have doctors,” she says.

“When I hear the word common, I hear Aaron Copeland’s ‘Fanfare for Common Man,’” her mother says. “I attended a performance in New York years ago when you were just a baby.” Her mother pauses. “What’s nice about a place like this is that people are neighborly; they help out.”

“It’s the same folks who do everything from organizing the parades to the potlucks. They’re the doers,” her father says as they move closer to the check-in table. “Did you know that if you’re sixteen you can be an election judge? All it takes is being a bona fide county resident, mentally competent, and four days of training before the event. A little pecker-schmecker who can’t even tie his shoelaces gets to count things up and call it in. And they get paid; in a town that’s not brimming with employment for children, it’s not a bad deal.”

Then it is their turn. Her parents step up and sign the book. You can see their signatures where they signed the last time—she finds it curious that a person’s signature doesn’t change over the years.

“Is this your first time, Meghan?” the woman asks, as she inscribes her name in the book.

“Yes.”

“Do you know how it works?”

“In theory,” she says. “But I do have a question.”

The woman nods.

“Do you know why it’s on a Tuesday?”

The woman smiles. “I asked my husband the same thing last night.

He had no idea, so I looked it up. It turns out the founding fathers had something in mind; by November, the fall harvest was done but the weather was still mild enough for travel. And because folks used to have to travel in order to take part, they couldn’t do it on a Monday because people wouldn’t travel on the Sabbath, and it couldn’t be November first because that’s All Saints’ Day, and some people care about that and so on.” She pauses. There’s a line forming behind Meghan. “Anyway, that’s what I learned—do you know how this next part works?”

“Not really.”

The woman hands Meghan a paper form. “You take this and go on over to one of those booths, make your selections, and then fold it over and bring the paperwork back over there and drop it in the sealed box. Easy-peasy.”

The booths are mini stalls with cardboard side screens like blinders you’d put up to keep a kid from cheating on a test or keep people from peeping over their neighbor’s shoulder.

“That simple?” Meghan asks.

“That’s the way we do it,” the woman says.

“How will they know who wins?”

“Tonight, after we close up, a few of us stay behind, open the boxes, and count ’em up.”

Is that what the sixteen-year-old does? Meghan wonders. “And then what?”

“We get on the phone and call the number in; when my granddad was a kid, they sent the number via wire—like an SOS to the state capitol.” She’s surprised at how rudimentary it seems, rinky-dink. She’s not sure what she imagined, but it was definitely something more substantive, professional, modern, maybe a big machine with lights, bells, whistles, the kind of thing they have in arcades. She imagines matching the picture of the person you’re supporting with their name, pushing the button, and then a lot of lights go off and simultaneously it registers on some great scorecard in the sky. Score one for the red team!

This, the paper form, the cardboard blinders, is beyond banal. All over the country people are doing the exact same thing? And by late tonight there will be a new order in the land? It’s more like an activity you’d do at a school to pick the new head of the class.

She looks over and sees her parents carefully pushing their forms into the sealed box.

Her father smiles at her—he’s passing the torch. His deep pleasure in this process reminds her of all the things they’ve talked about over the years—all the car trips and vacations they’ve taken to historical sites. This is the passion he shares. He doesn’t talk about himself or his childhood. He talks about historical figures, battles, wars, treaties, and the three branches of government. She’s been brought home to vote—to go on this electoral journey as a kind of indoctrination.

She ducks into her booth, fills out the form, folds as directed, then hurries over and stuffs it into the box.

On the way out, there’s a table set up with an enormous industrial-size coffee urn, glass bottles of milk, and a box of fresh glazed donuts, still shining while the sugar dries.

She picks up a donut. Her mother sees her do it and looks horrified. It’s hard to know if it’s the calories, the idea of a donut for breakfast, or the fact that it’s been sitting out and possibly touched by others. She’s caught, donut pinched between her thumb and middle finger. The glaze begins to melt. She squeezes, denting the dough. As she’s holding the donut, unsure what to do, her father leans over and takes a bite.

“Best damn donut I ever had,” he says. “That had to be made within the last hour; I can taste it; the yeast is still rising.”

Her mother reaches over, plucks the donut from between Meghan’s fingers, and drops it into a trash can. The expression on her mother’s face is one of enormous satisfaction—like she’s put out a fire. Meghan is left with sticky fingers. She puts her hand in her pocket and thinks about when she might be able to sneak a lick.

“Well, that’s all she wrote,” Sonny says, as they’re back in the car. “Our duty is done,” her father says.

They drive straight from the church to the airport. Sonny smokes with the window down—the smoke catches the air and blows into the back seat. Meghan can see her mother take a deep breath.

As soon as they’re on the plane, her father turns to her and asks, “So, what did it feel like?”

She can’t tell her father what she’s really thinking; it reminds her of another first—her virginity and how losing that was also less spectacular than it was supposed to be.

She can’t tell him that she finds the whole thing so basic that it is causing her a new kind of anxiety, the deep existential ache that nothing is as previously represented; nothing in reality is as good as the idea she’s been sold. She can’t tell him any of it because she knows it would break his heart.

Luckily, before she can say much, he continues. “Back in Connecticut we used to vote on a device that was gunmetal gray. You went in, pulled a little half curtain around you like in a photo booth, and then you’d toggle the switches up or down depending on which man you were for. When you were done, you’d pull an enormous lever with a black handle to register your vote. Every time I threw that lever to the right, I felt like I was doing something major, starting up a time machine or launching an atomic bomb, I was never sure which.” He pauses. “I’m so proud of you. Getting yourself out here to cast your ballot with us means a lot.”

“Thanks,” Meghan says. “It meant a lot to me, too, we’re making history one day at a time. I cast my vote in honor of all those who have come before me and with an eye to the future ahead.”

“Is that a line from a poem?” her mother asks.

“No, I just made it up,” she asks.

__________________________________

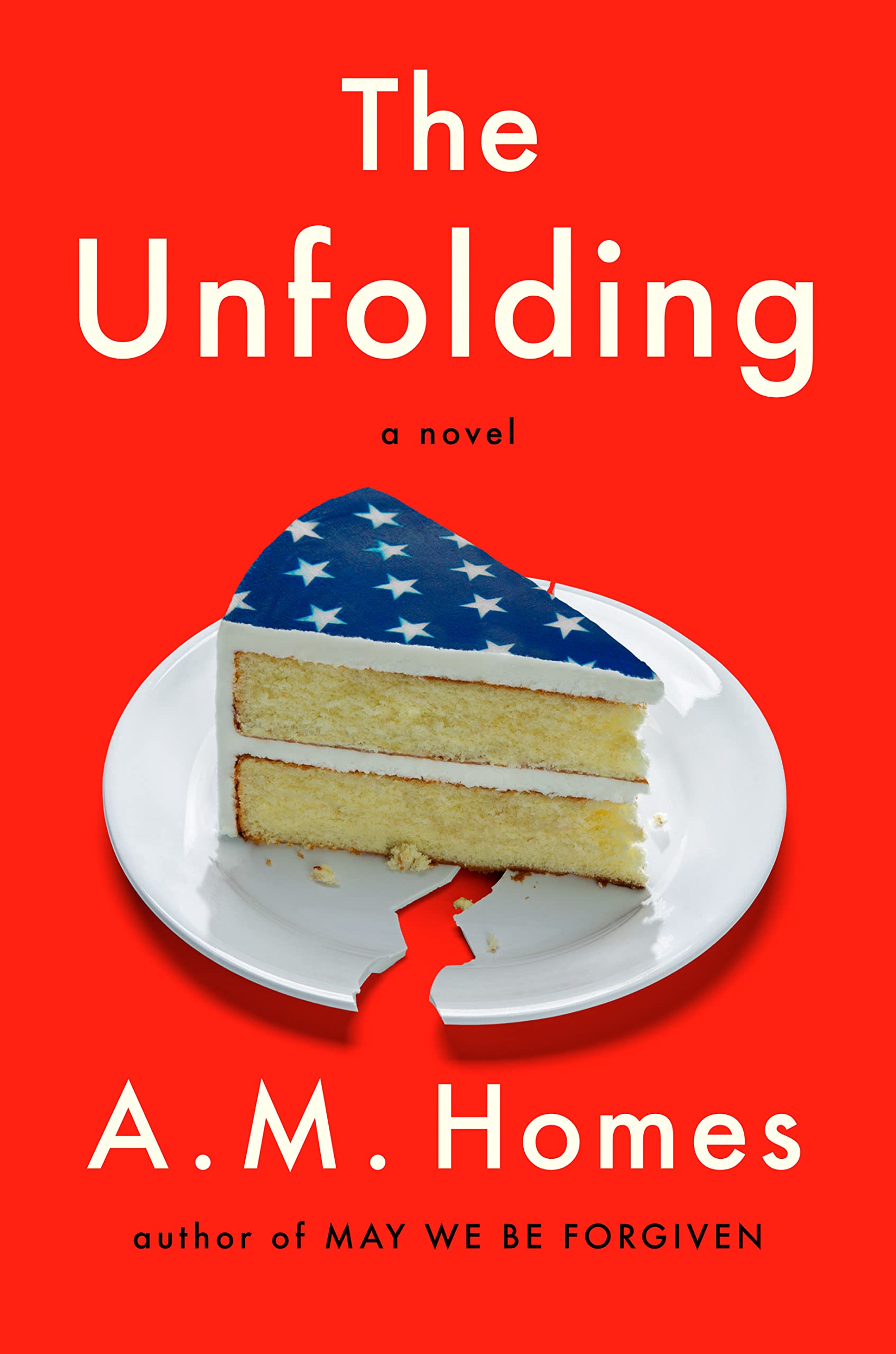

From The Unfolding. Used with permission of the publisher, Viking. Copyright 2022 A.M. Homes.