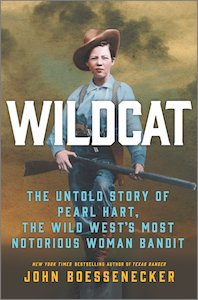

The True Story of Pearl Hart, Straight-Shooting, Poetry-Writing Woman Bandit

John Boessenecker on the Most Infamous Woman in America, Circa 1899

Pearl Hart stroked her pet wildcat as she leaned back on the bunk in her cell in the courthouse in Tucson, Arizona Territory. It was 1899, and she was the most infamous woman in America. Pearl and her male companion had held up a stagecoach, disarmed the driver and passengers, and stolen their money and guns. They escaped on horseback, but were captured after a long manhunt in the remote high desert. Her story made newspaper headlines, for in an era when a woman’s role was primarily domestic, Americans were simultaneously shocked and thrilled by the concept of a real woman bandit.

Journalists and cameramen flocked to the jail, seeking interviews and photographs. They found her a walking contradiction: a petite, attractive young woman who could alternately act like a street ruffian or a feminine ingenue. She dressed in rough cowboys’ clothing and carried a pair of six-guns. Pearl Hart talked tough, smoked cigarettes, drank liquor, used morphine, and had sex with countless men. At the same time, they saw that she was extremely bright, well-spoken, and a voracious reader. She could knit, sew, and write poetry, yet also shoot straight with a heavy Colt’s revolver. Americans had never seen or heard of anyone like her.

The public interest in Pearl Hart grew so intense that Cosmopolitan magazine sent two correspondents to seek an in-depth interview. Even in 1899, Cosmopolitan was the country’s most popular women’s publication. The journalists met a friendly, talkative woman in her late twenties, with her long brown hair tied up in a bun. She wore a man’s dark-colored shirt, open at the neck, and trousers held up by suspenders. Pearl loved publicity, and despite the fact that she had been charged with stage-coach robbery and faced a long prison term, she had no qualms about telling her story.

When I was but sixteen years old, and while still at boarding school, I fell in love with a man I met in the town in which the school was situated. I was easily impressed. I knew nothing of life. Marriage was to me but a name. It did not take him long to get my consent to an elopement. We ran away one night and were married. I was happy for a time, but not for long. My husband began to abuse me, and presently he drove me from him. Then I returned to my mother, in the village of Lindsay, Ontario, where I was born.

Before long, my husband sent for me, and I went back to him. I loved him, and he promised to do better. I had not been with him two weeks before he began to abuse me again, and after bearing up under his blows as long as I could, I left him again. This was just as the World’s Fair closed in Chicago, in the fall of 1893. Instead of going home to my mother again, as I should have done, I took the train for Trinidad, Colorado. I was only twenty-two years old. I was good-looking, desperate, discouraged, and ready for anything that might come.

Pearl continued on in detail, describing her adventures and misadventures on the Arizona frontier. The two correspondents, scribbling furiously, wrote it all down, oblivious to the fact that they were helping create one of the most enduring legends of the American frontier. For although Pearl Hart was the West’s most notorious woman bandit, her true story has long been lost in the mists of the past. Her personal history is thoroughly obscured by legends, many of them created by Pearl herself.

For the next century, newspaper reporters, magazine writers, and historians repeated, and even invented, countless wild tales about her: she was the West’s first woman stage robber; she was the West’s last stage robber; she was the daughter of a wealthy Canadian family; she was a virtuous schoolgirl in Phoenix; she performed with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. Even her identity has been the subject of controversy: her real name was Mrs. Frank Hart, Pearl Bandman, Caroline Hartwell, Pearl Taylor, Mrs. E. P. Keele, Mrs. Earl Lighthawk, and Pearl Bywater. She was born in Canada, Ohio, and Kansas. Her husband was Brett Hart, Frederick Hart, Frank Hart, William Hart, James Taylor, Dick Baldwin, Harry Boardeman, Joe Boot, and Calvin Bywater.

But most of that is not true. The tales she spun in the Tucson jail have confounded authors, researchers, and historians for the last 120 years. Although Pearl Hart has been featured in hundreds of magazine articles and books, not one of them comes close to an accurate depiction of her life. But now, modern digital newspaper archives and genealogical data banks have provided the key to unraveling the mysteries of Pearl Hart’s career. Her authentic story is alternately romantic, exciting, and disturbing. For the truth is far more fascinating—and instructive—than the myths spread by popular writers, casual researchers, and deliberate fictioneers.

Pearl Hart was a woman far ahead of her time. She was self-reliant, adventurous, unconstrained by convention, and sexually liberated. Those attributes were extremely rare for a woman in the nineteenth century. Then, few women worked outside the home. They dressed modestly, raised children, cooked, cleaned, and managed the household. In rural America, they helped tend the family farm and often labored next to their fathers or husbands in the fields. In urban areas, there were more opportunities for employment for women: as domestic workers in middle- and upper-class homes, as seamstresses in dress shops, and as mill girls in factories and textile mills. And despite such work obligations, women were still expected to marry, bear children, and be the bedrock for moral, religious, and familial stability.

In the American West, most pioneer women and girls came to the frontier with their fathers, brothers, and husbands. Yet in frontier boomtowns, the first female arrivals were often prostitutes. As the lyrics of a popular song of the 1849 California Gold Rush proclaimed:

The miners came in forty-nine,

The whores in fifty-one;

And when they got together.

They produced the native son.

In that era, there were no welfare subsidies, no unemployment benefits, and no job security. For poor, uneducated, and unskilled women, prostitution often provided the only means of survival. Because of the huge gender imbalance on the frontier, prostitutes in the West were not held in the same disrepute as those in the East. Yet the life of a so-called fallen woman was brutal and debilitating. Many died of alcoholism, drug abuse, and violence. But many more left the profession, married, and led stable and respectable lives thereafter.

Among the most notable examples are Josephine Marcus Earp and Allie Sullivan Earp, the wives, respectively, of Wyatt Earp and his brother Virgil. Both lived to old age, dying in the 1940s after leaving memoirs of their famous husbands. Modern research has revealed that both Josephine and Allie had been frontier prostitutes in the 1870s, and their husbands were fully aware of their pasts.

Myths about women in the Old West abound, and Hollywood has been the leader in creating them. Beginning in the 1920s and ’30s, a staple in Western films has been the cowgirl: a woman who rode and dressed like a man, wore blue jeans, boots, and a cowboy hat, and often sported a six-shooter hung low from a cartridge belt. That was a screenwriter’s fantasy, for cowgirls did not exist in the Old West. The term first appeared in the 1880s and was used to describe female performers in Wild West shows. In that era, women on horseback wore skirts and rode sidesaddle. For a woman to ride like a man astride a horse was considered sexually suggestive and highly improper.

Prior to 1900, women almost never wore men’s trousers. In fact, most communities had laws against cross-dressing, and women who ventured out in male attire were subject to arrest. Split skirts first became popular for female bicyclists during the bicycle craze of the 1890s. But split skirts for horsewomen were virtually unknown before 1900, and such attire continued to be scandalous until the 1920s. That is why the American public was shocked by widely published photographs of Pearl Hart, wearing men’s clothing and armed to the teeth with a Winchester rifle and a brace of revolvers.

Most Western filmmakers have been almost clueless about how women looked, dressed, and acted in the real West. Since the 1920s, any Western movie can be immediately dated by the hairstyles of its actresses. In Westerns made in the 1920s, the women wear 1920s hairdos; in Westerns made in the 1970s, the actresses sport 1970s hairstyles, and so on. Unlike depictions in fiction and film, American women in the late nineteenth century did not exhibit long hair draping over their shoulders. A woman was expected to keep her hair up or wrapped in a bun, for it was considered immodest for a woman to display her flowing locks. Only her husband or her family were allowed to see her with hair to her shoulders, and then only when she was at home or preparing for bed. Thus originated the expression let your hair down, meaning to relax and be oneself. And in the real West, women—even prostitutes—wore demure Victorian clothing, without the cleavage so often seen on screen.

Contrary to Hollywood films, there was not a single female gunfighter in the history of the Wild West. That is not to say that women did not participate in gunplay. Nineteenth-century newspapers are filled with accounts of women—from common prostitutes to upper-class matrons—shooting each other as well as men. Love triangles and domestic disputes were the most common cause of such female violence. Television and movie Westerns also frequently show supposed saloon girls drinking, gambling, and rubbing shoulders with men in bars. Such depictions are wildly inaccurate. Women in a saloon or gambling hall generally worked in a brothel situated upstairs. Respectable women were not allowed in saloons. If a woman stepped into a saloon or a card parlor, she would be immediately branded a prostitute and could never again show her face in polite society.

The vast majority of women in the nineteenth century did not have sexual relations outside of marriage. They did not smoke, and they certainly did not use opium and morphine. They did not wear men’s clothing, ride astraddle, or carry six-shooters. Pearl Hart broke all these taboos and then some. She swore, smoked, drank, robbed, rode hard, broke jail, and used men with abandon. The Old West never saw another woman like her.

____________________________________________________________

Excerpted from Wildcat: The Untold Story of Pearl Hart, the Wild West’s Most Notorious Woman Bandit by John Boessenecker, Copyright © 2021 by John Boessenecker. Published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

John Boessenecker

John Boessenecker is the author of nine books, including New York Times bestseller Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde. He has received the Spur award from Western Writers of America, the Best Book award from Westerners International, and in 2011, 2013 and 2019 True West named him Best Nonfiction Writer. He has appeared frequently as a historical commentator on PBS, The History Channel, A&E, and other media. His latest book is Wildcat: The Untold Story of Pearl Hart, the Wild West’s Most Notorious Woman Bandit. He lives near San Francisco, California.