The Treacherous Start to Mary and Percy Shelley's Marriage

Anxious, Impatient, and Seasick While Sailing Through a Storm

My heart, which was before sorrowful, now swelled with something like joy.

![]()

It’s easy to imagine a Romantic portrait making the most of young Mary Godwin’s ethereal pallor: unfortunate that we often catch her in the decidedly un-ethereal process of throwing up. In the next scene she lies exhausted by seasickness and fear on board a small wooden sailing vessel. The boat is being dwarfed by storm waves that swell under and around it in the moonlight. The time is just before midnight, and a crossing that the sailors promised would be “only two hours’ sail from the shore” has already been going on for more than six. The horizon is “red and stormy”; there are vivid flashes of lightning.

Mary is only 16, and she is running away with Percy Bysshe Shelley, a man five years her senior who is not merely already married but the father of a young child. It’s July 28, 1814, and they’re in the middle of the English Channel, and of a summer storm that has come on with the night:

Suddenly a thunder squall struck the sail and the waves rushed into the boat; even the sailors believed that our situation was perilous; the wind had now changed, and we drove before a wind, that came in violent gusts.

The crossing the lovers are attempting, between Dover and Calais, is a mere 23 nautical miles. When they left Dover at six in the evening on what was not only the hottest day of the year but “a hotter day than has been known in this climate for many years,” “the evening was most beautiful; the sands slowly receded; we felt safe; there was little wind, the sails flapped in the flagging breeze.” But, like many straits, the Channel is concentrated into ferocious currents and susceptible to sudden storms. It’s also markedly tidal, and the 12 or more hours this crossing takes pass through a complete cycle from one low tide to the next.

Eventually, at around 4:20 am, amid heavy wind and continuing lightning, a stormy dawn breaks over the laboring boat. Luckily, because the sailors “succeeded in reefing the sail,” the wind finally drives them “upon the sands” of Calais, where “suddenly the broad sun rose over France.” This is a striking image of rebirth: of near-death and the transfiguring experience of survival. But though taken from Mary’s Journal, it’s actually written by Percy. Mary herself won’t write in what is the earliest surviving volume of her Journal until over a week later.

She will, though, rewrite this account within the next three years, when she publishes an account of the journey on which she and Percy have embarked, her History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, of 1817. At this point—when she ghosts him as he has already ghosted her—the young lovers’ voices overlap each other, like their limbs piled on each other’s in exhaustion or sleep. Which is just how Percy portrays the crossing. In his account Mary lies all night between his knees, as he holds her head on his chest. “She did not speak or look,” and he believes she “did not know our danger.”

But Mary knows the reality of shipwrecks from her time in Scotland. Who can say whether the too plausible estimate of a two-hour crossing the youngsters are given as they charter the boat is triggered by unusually anxious questioning on her part? Or is her famous pallor so deepened by the motion sickness she’s already suffered earlier in the day, on the way to Dover, that even the boat’s captain notices it? As Percy records:

Mary was ill as we travelled, yet in that illness what pleasure and security did we not share! The heat made her faint; it was necessary at every stage that she should repose.

I’ve always wondered whether this passage is in code. What exactly does “what pleasure and security did we not share” mean? Mary has always been a poor traveler, and her vulnerability may make her new lover feel protective and tender: able to be of intimate use. But she is also possibly in the earliest stages of pregnancy—just around the time, in other words, that she may be realizing she could be pregnant. For in a famous entry in the Journal made just a few days later, on August 4th, Percy will record that he thinks of June 27th as his “birthday”: the date, just over a month earlier, on which Mary first either told him she loved him or made love with him, or both.

“Percy has two equally powerful needs: to believe himself to be good, and to get what he wants.”

It’s even possible that he realizes, or at least suspects, that she’s pregnant before she does. He has prior experience, after all—he’s a married man with a small daughter and a pregnant wife while Mary does not even have a mother to tell her about sex and pregnancy. (She was only a child of five when her stepbrother William was born: hardly of an age to witness and understand human reproduction.) Does Percy feel “pleasure and security” in the signs of a pregnancy which he recognizes, and which he knows binds Mary to him more surely than any choice she could now make? This is, after all, an elopement without the “security” of a marriage at the end of it. Indeed, technically it’s not elopement at all. Yet, because the couple believe in the “common law” commitment of consummated romantic love rather than a legal contract, it is elopement in their terms. A “common law elopement,” as it were.

Next February, when Mary’s baby is born on the 22nd, Percy will record, again in Mary’s Journal, that the baby is premature, “not quite seven months” and so not expected to live. In fact, she does survive—for just under a fortnight—something fairly exceptional before the days of intensive-care incubators. Percy’s calculation assumes the baby was conceived around the date of this stormy night at sea. But if she was conceived not in France but a month earlier, in London, she would have been only one month premature.

This is something for which we can have no definite proof and only the circumstantial evidence of Mary’s motion sickness and the baby’s (brief) survival. But there’s something else to bear in mind. Percy has two equally powerful needs: to believe himself to be good, and to get what he wants. It would be entirely in character for him to feel guilt about seducing Mary while she’s living under her father’s roof, but to argue that once she runs away with him they are de facto—”in the eyes of God”—married, and to adjust the date of the baby’s conception accordingly.

Mary and Percy have risked the night crossing because they’re too anxious or impatient to wait for the packet ship sailing the next day. They have already hired four horses instead of the more usual two at Dartford, “that we might outstrip pursuit” on their race down to Dover. They aren’t thinking clearly; they’re in love. But it is, one can’t help feeling, a typical piece of Romantic overreaching since their pursuer, Mary’s stepmother, manages to arrive at their hotel at Calais on the very same day they do: presumably by the packet, presumably after a shorter, safer and altogether cheaper crossing. Or else you could view these big gestures as calculating rather than spontaneous. The advantage gained is just enough. Mary’s stepmother does indeed catch up with the runaways in Calais. But by then it’s too late: Mary has been publicly “ruined,” because she has passed that all-important (though as it happens entirely un-sexual, storm-tossed) night with Percy and because, arriving in another country and registering with him at a hotel there, she has definitively eloped. Percy, who has form in eloping with 16-year-olds—his wife, Harriet, was the same age when he ran off with her—must understand this, at least, perfectly well. Whatever happens next between him and Mary, he has ensured that there’s no way back for her into ordinary society. He truly has snared her.

What does Mary think or know, as she lies in the paralyzing grip of seasickness? Is she astonished by the speed of events that have got her on board this small craft, lurching so horribly in the grip of a Channel storm? Nausea turns the body into a liquefying burden. Does Mary really have no second thoughts, no longing to be safely back on dry land? Illness seems mercifully to embroil her, and “as is my custom when thus affected, I slept during the greater part of the night, awaking only from time to time to ask where we were, and to receive the dismal answer each time—’Not quite half way.'” Even a quarter of a century from now, looking back over her life from her forties, she will remember not this flight but her miscarriage in 1822 as her first near-death experience.

“In 1814 reputations have material consequences: unless, like Percy Bysshe Shelley, you are heir to a baronetcy and can buy the freedom to do as you want.”

And after all, on July 29, 1814 the sun rises “broad, red and cloudless over the pier,” and Mary, walking across the Calais sands, hears “for the first time the confused buzz of voices speaking a different language from that to which I had been accustomed.” She observes the typical Normandy costumes: “the women with high caps and short jackets; the men with earrings; ladies walking about with high bonnets or coiffures lodged on the top of the head [. . .] without any stray curls to decorate the temples or cheeks.” She will never forget these initial impressions. She’s a teenager, abroad for the first time in her life. Although Percy’s Journal entries record the runaways’ movements, Mary’s recollections three years later are alive with observational detail. Like many a subsequent English traveler in France, she remarks that, “The roads are excellent”; even so, she finds the cabriolet in which they embark for Paris “irresistibly ludicrous.” She remembers walking the outer earthworks fortifying Calais—”they consisted of fields where the hay was making”—and notes, “The first appearance that struck our English eyes was the want of enclosures; but the fields were flourishing with a plentiful harvest.”

Meanwhile Mary’s stepmother has arrived, presumably on the same sailing as the runaways’ boxes, something that we can guess helps her locate them at their hotel. The packet, too, has been “detained by contrary wind,” and Mary Jane Godwin, who travelled through the night from London, must be exhausted. As usual, it’s she who has the dirty work of trying to resolve the family’s newest drama; as usual, William Godwin remains ensconced in London. And so she must face down the casual mockery a middle-aged woman traveling alone can expect. “In the evening,” Percy nastily comments in Mary’s Journal, “Captain Davison came and told us that a fat lady had arrived, who had said that I had run away with her daughter.”

The entry implies that this is hysterical exaggeration. But of course, it isn’t. Besides, Mrs Godwin is not concerned with her stepdaughter Mary. She has come to rescue Jane. For here we need to pan out a little, and observe that Mary and Percy are not unaccompanied. Astonishingly, they’ve brought with them Mary’s stepsister Jane. I want to write for reasons best known to themselves. But that would be a derogation of the biographer’s duty, which is to try and understand the muddle these three young people—even Percy is at this date still only 21, and both girls are 16—have got themselves into.

It’s a muddle that will only get worse. Two’s company, three’s none, and Jane’s triangulating presence will shape the young couple’s entire relationship. For Mary’s sake, one wishes Mrs Godwin could succeed in “rescuing” Jane from this adventure and persuade her to return to England the next day. The worst of it is that she so nearly does. Mary Jane talks her daughter into spending the night with her in her own room, so she hasn’t had an unchaperoned stay at a hotel but merely overnighted with her mother in another country. In the morning, Percy notes, “Jane informs us that she is unable to resist the pathos of Mrs Godwin’s appeal.”

“Pathos” is a privileged young man’s shorthand for the whole complex of consequences that Mrs. Godwin will try to unfold for her teenaged daughter—who can hardly be the most receptive of audiences. We know, as Jane probably does not, that Mary Jane has experienced at first hand the cost of toppling from respectability. She has since laboriously reconstructed herself, putting over a dozen years of hard work and sheer willpower into keeping the Godwin household financially and, despite the reputation of the first Mrs. Godwin, socially respectable. That both these enterprises may actually have been complicated by her own and her husband’s incompetence—the bookshop is in fact ruinously costly; it’s Godwin himself who through that poorly judged biography made his first wife into a figure of ill-fame—is beside the point.

Mary Godwin will always be the controversial Mary Wollstonecraft’s child but, in marrying Godwin, Mary Jane has gambled with the future of her own daughter. So she has been particularly keen to see the girls working with a private tutor, like young ladies rather than a shopkeeper’s daughters, and assiduous in making sure that sulky, teenaged Mary and her unsightly skin disease are not on display at Skinner Street. If Jane returns home, both she and Fanny, who as Wollstonecraft’s daughter is always going to be the harder sell—and whose prospects are in any case limited by her looks and lack of general sparkle, according to family lore—have at least the chance of marriage and a home of their own. If she does not, everything is changed not only for the two young women themselves but also for the rest of the family; and William and Mary Jane herself will for ever be figures of scandal.

In 1814 reputations have material consequences: unless, like Percy Bysshe Shelley, you are heir to a baronetcy and can buy the freedom to do as you want. With a hypocrisy that would be funny if it weren’t so sorry, Percy, soaring above Mary Jane’s “pathos” on wings of aristocratic privilege, counters her arguments by encouraging Jane to think of own her situation in terms of the French Revolution, which has done away with the very privileges he himself enjoys; of France’s “past slavery and [. . .] future freedom.” Sure enough, Mary’s stepsister changes her mind, telling her mother she won’t return to England; whereupon, “Mrs. Godwin departed without answering a word.”

But it’s Mrs Godwin who is right—about all of it. Jane will never marry; within 26 months Fanny, understanding her life to have been made supernumerary by her sisters’ adventures, will kill herself. The rumor will go round London that Godwin has sold two daughters to Percy for £1,500; and this formerly distinguished philosopher will struggle for money and recognition for the rest of his life. Percy’s fantasy of freedom will even infect the girls’ little brother William junior, now just ten years old, who in a week’s time, on August 8th, will run away from home. Luckily he is found safe and well: but not for two whole days.

Damage runs through the Godwin household like a rapid crack through the jerry-built Skinner Street property, as even Godwin himself has realized it will. Just three days before the elopement he had written to Percy, urging him to stay with his “innocent and meritorious wife” Harriet, and to leave untouched “the fair and spotless fame of my young child,” adding that “I could not believe that you would enter my house under the name of benefactor, to leave behind an endless poison to corrode my soul.” The letter is the near-culmination of nearly four weeks of push-me-pull-you during which Godwin grounds Mary in the upstairs schoolroom, admonishes both his daughter (on July 8th) and her accomplice his stepdaughter (on July 22nd), and works hard and successfully on Harriet Shelley’s behalf to separate her husband, Percy, from his other current amour, Cornelia Turner (after a visit from the girl’s mother on July 18th, and one he pays to Harriet Shelley herself on is July). He also stoutly refuses Percy a list of continental contacts to expedite the proposed elopement.

“The Godwin girls have been conditioned to associate both elopement and a European destination with revolution and freedom.”

For Percy has announced his plan directly to Godwin on July 6th. This approach, remarkable in its effrontery—or naiveté—seems to be the first time that it has occurred to anyone in the Godwin household, apart from Jane, that Mary and Percy might be getting close. That’s all the more surprising because Mary Jane, no fool when it comes to family matters, is on the alert. She has already sent Fanny away to Wales, possibly to have her health or her character strengthened as Mary’s has been by her time in Scotland; but possibly also because she is thought to be falling in love with Percy. (This is something Percy himself seems to believe, as his reaction to Fanny’s death will show.)

Percy’s behavior seems less naïve when we remember that Godwin is himself the social revolutionary who declared, in 1793’s An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, that man should “supersede and trample upon the institutions of the country in which he lives,” and in particular marriage. But that was two decades ago. Even one decade ago he was already writing in the introduction to his 1805 novel Fleetwood, subtitled The New Man of Feeling and a study of a marriage, that he no longer believes action “by scattered examples [can] renovate the face of society.” Instead he now thinks radical ideas should be disseminated “by discussion and reasoning.” And, of course, he is himself twice married.

As a late-flowering paterfamilias, however, his authority over his daughter’s relationship with Percy is undermined by the fact that the latter has agreed to be his benefactor to the tune of £1,250. Indeed, a further £1,750 that Percy had originally promised Godwin is now the very money he plans to use to take Mary to Europe. It’s easy to see how readily this cross-current of financial implication could be seized on by the teenagers of the Godwin household, brought up to dream of revolutionary action, as proof that it’s only grasping materialism that objects to the radical social and sexual rearrangements Percy proposes. The Godwin girls have been conditioned to associate both elopement and a European destination with revolution and freedom. With the double solipsism of privilege and youth, Percy can encourage them to conflate free love with social liberty, possibly even supplying egregious financial detail to the young woman he hopes will run away with him. That he’s leaving a pregnant wife penniless and socially in the lurch—that once love wears off a woman can simply be abandoned and, if she is, will have no way to support herself—must seem to the teenagers like the tedious small print of a shining new social contract.

Perhaps Percy isn’t manipulative, just thoughtless: or, better still, a true social revolutionary. He is, after all, gambling with his own reputation—to a limited extent. A double standard may make the promiscuous 19th-century gentleman into a “gay dog,” but even this differentiates between having affairs and actually abandoning a wife. And Percy does genuinely live by his ideals. After all he was sent down from Oxford, in 1811, as a result of publishing The Necessity of Atheism not anonymously but under his own name; and he has subsequently tried out a number of model lifestyles: for example in Wales, at remote Cwm Elan and communitarian Tremadog. Indeed, it was in attempting to raise money for the latter, a model settlement on newly drained land near Porthmadog, that he first met Godwin in 1812. He has also already “rescued” another 16-year-old from what he believed to be the oppression of old-fashioned authority: his wife, Harriet, nee Westbrook, was a schoolgirl when he eloped with her to Edinburgh shortly after being sent down from university.

Consciously at least, these recurring attempts at liberation and communitarian living cannot be just sexually motivated: shortly after his elopement with Mary, Percy will also contemplate liberating his own sisters, Elizabeth and Hellen, from their school in Hackney. Revolutionary principles genuinely inform his thinking and writing. The former schoolboy chemist, best known at Eton for blowing things up, has by the summer of 1814 already written the short lyric “Mutability”—which reveals his interest in radical transformation and his sense that “Nought may endure but Mutability”—and the 2,000-line, nine-canto philosophical fantasy Queen Mab, which combines this sense of mutability with the Godwinian idea of “necessity” to predict social progress for the world. This generalized idealism has been deeply influenced by Godwin’s Political Justice, and Percy and Mary will reread that book in the first difficult weeks of their post-elopement return to London, as if they hope to find in it some definition or justification of their position.

__________________________________

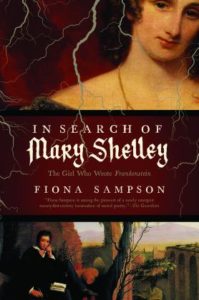

From In Search of Mary Shelley. Used with permission of Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2018 by Fiona Sampson.

Fiona Sampson

Fiona Sampson is a poet who has been shortlisted twice for the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Forward Prize. She has received the Cholmondeley Award, the Newdigate Prize, and the Writer’s Award from the Arts Councils of England and of Wales, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Wordsworth Trust. She is the author of In Search of Mary Shelley.