The Trailblazing Illustrator and Mountaineer Who Explored the Wild North

Pamela Henson on Mary Vaux Walcott’s Wildflowers

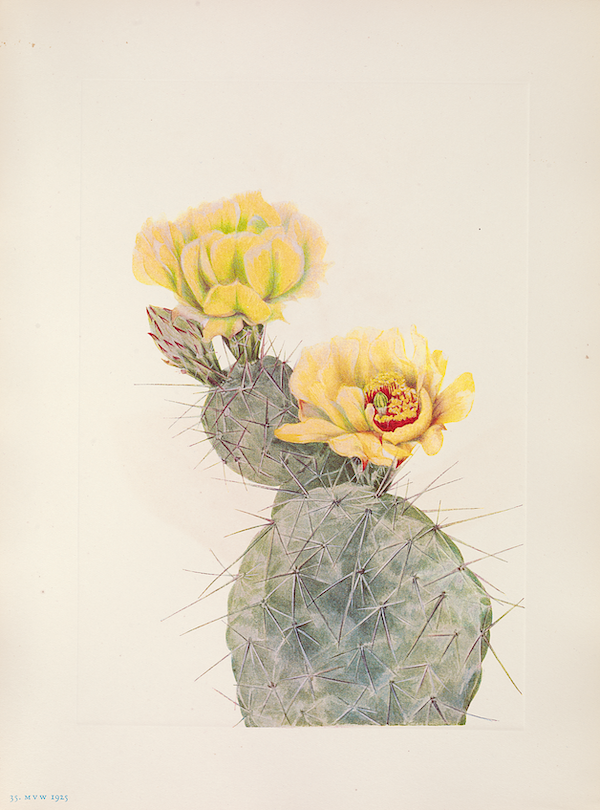

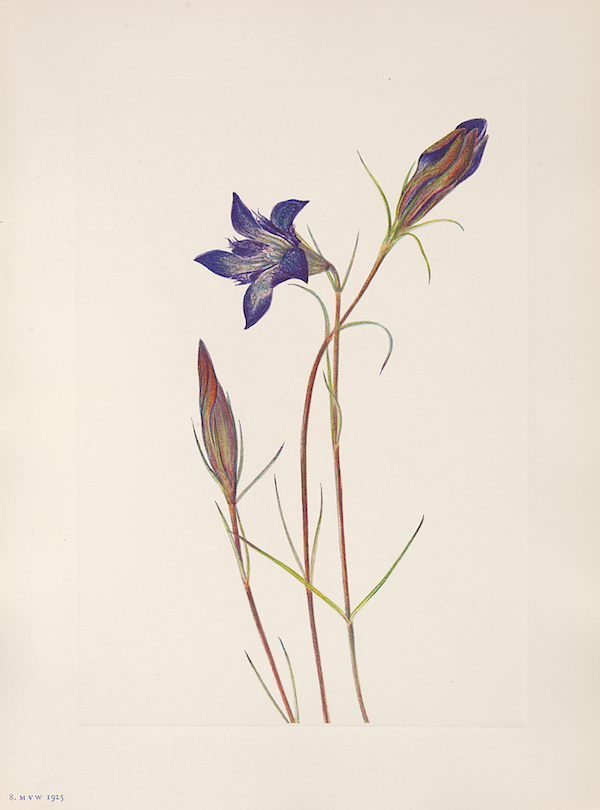

In 1925 Mary Morris Vaux Walcott was delighted to receive a copy of the first volume of her five-volume set of North American Wild Flowers, the product of many years of work. Any income from their sale was destined to support the Smithsonian Institution, which was led by her husband, Charles Doolittle Walcott.

When I came to work at the Smithsonian in the early 1970s, I found several beautiful framed flower illustrations that had been left by an earlier staffer. As I put them on the wall, I wondered where they came from. And as I walked the hallways and went to meetings in offices, I saw even more of them. Who drew these flowers and why were they seen so often at the Smithsonian? They have become part of our natural environment. Little did I know how much I would learn about their creator in the years to come.

In 1870, at the age of ten, Mary was given a painter’s box that accompanied her for the rest of her life. She soon developed an aptitude for capturing the natural world, especially landscapes of the dramatic regions her family visited during summer vacations out west. Botany and drawing were considered very appropriate avocations for educated young women, although most sat in their gardens rather than scaled peaks and crossed glaciers.

In 1887, Mary, her father, and her brothers traveled 10,000 miles by rail, carriage, stagecoach, ferry, horseback, and on foot through the American West and Canada. This was their first trip to the Canadian Rockies, through which they traveled via the new Canadian rail line. They went to San Francisco, visiting Quaker families along the way, and survived a train crash and derailment.

Traveling along California to Oregon and Washington, they reached Glacier House in British Columbia, newly constructed by the Canadian Pacific Railway for travelers. A series of these accommodations across the country served meals, in place of dining cars. Glacier House was rustic in design and located near Illecillewaet Glacier. The Vaux family immediately set up their cameras and captured what may be the earliest photographs of the glacier.

For over forty years the Vauxes photographed Illecillewaet from that same spot, to capture any changes, since George Sr. was very interested in glacial science. And indeed those photographs clearly documented the recession of the glacier over more than four decades, a very early record of environmental change. As they traveled east across Canada, they encountered a phenomenon well known to us today, as wildfires obscured their view for miles upon miles.

Mary Vaux Walcott revealed the delicate but hardy beauty found off the beaten path across North America.

After 1887 Mary returned to western Canada almost every summer with her brothers and became a skilled mountain climber, outdoorswoman, and photographer. A member of the Alpine Club of Canada, she advocated women wearing trousers, rather than skirts, for safer climbing. When she was not scaling the face of another mountain, she might be photographing or painting a nearby landscape scene.

All of the Vauxes remained interested in photography, capturing the beauty of the natural world as well as documenting their scientific observations. One summer a botanist asked Mary to paint a rare blooming arnica. The botanist’s pleasure with her rendering of the flower encouraged Mary to begin serious botanical illustration. For decades after, Mary explored difficult terrain across the Canadian Rockies, searching for rare flowering species to paint.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Painting wildflowers poses many challenges—they are, after all, wild, not growing in your garden or hothouse. First you must find them—where do they grow, in bright hillside sun or deep forest shade, among rocks or along streambeds, in sandy or loamy soil? She wrote that there were alpine species that were so rare she only saw them in bloom two or three times in all her years of exploration. You also need to know when that plant blooms—morning or evening, in winter’s snow or the heat of summer, in dry or rainy spells, warm or cool temperatures? Then you need to identify what insects pollinate it and when they are active. It’s also helpful to know what creatures are likely to consume the plant before you can find it. Mary often made numerous visits to potential sites before finding the plant in bloom, lugging her paint box and supplies each time.

Once she found the plant blooming, she had to work quickly under less than ideal circumstances—no matter how uncomfortable her perch was or how many mosquitoes were biting her. She armed herself with netting and thick clothing—the mosquitoes especially liked the back of her neck as she bent over to work. But time was of the essence. Unlike roses that have been bred to last a week or more after being cut, uncut wildflower blooms rarely last more than a day, often only a few hours.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Mary always worked on-site—depicting the wildflower in watercolors in nature to be sure she got the color shade and hue correct. Many other botanists would do a quick sketch in the field of the shape of the blossoms in pencil and then rapidly indicate colors on a palette on the side of the page. Mary felt this often led to inaccurate images that did not capture the intensity of colors or the way colors blended into one another. She would work at the site as long as the plant and sunlight lasted, up to seventeen hours at times, before returning to camp. If she was not entirely satisfied, she would produce another, more accurate finished version in camp.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Mary’s paintings captured unknown and poorly known wildflowers—previously described from only a colorless withered stem, flowers, and leaves, pressed flat for preservation in an herbarium. Her work captured the wildflowers at their most vibrant and taught the world about the ephemeral beauty that appeared and disappeared daily in the remote hillsides, crevasses, and streambeds of the wild North.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

By middle age, however, Mary was best known for her mountaineering skills. In 1900 she became the first nonnative woman to climb Mt. Stephen (10,000 feet), and with her equally intrepid childhood friend, Mary Schaffer Warren, also a Philadelphia Quaker and botanical illustrator, she explored the formidable Nakimu (Deutschmann) Caves. She was also the first woman over Abbot Pass in Lake Louise. In 1908 Mary Schaffer named one of the peaks in the Maligne Lake Valley “Mount Mary Vaux” in her honor. It is some 10,881 feet high, at 51°16 north latitude and 116°32 west longitude in British Columbia.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

The early twentieth century brought many changes to Mary’s life. The tight family band of Vaux explorers was dissolved. In 1908 her youngest brother Willie died of tuberculosis. The year 1911 was the last year her younger brother George Jr. traveled to the Canadian Rockies, due to the press of work and family responsibilities. And her father, as he grew older, ceased his trips as well. Mary made the decision to continue alone their photographic study of the receding Illecillewaet Glacier in British Columbia and push further into the unknown in her exploration of Canada’s mountains. She traveled by herself or with Quaker women friends. In 1913, when she was fifty-three years old, she climbed Mount Robson, the highest peak in the British Columbia Rockies. In 1935 she celebrated her seventy-fifth birthday with a twenty-mile trek on horseback.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Mary Vaux Walcott’s life story shows the major transitions in women’s roles as the nineteenth century ended and the twentieth century began. Unlike most families drawn to explore new regions opened up by railroads, the Vauxes included Mary in their ascents to high mountain peaks, at a time when most women stayed behind in camp. In the twentieth century she began traveling independently and to take her nature sketches more seriously. Publishing Wild Flowers of North America was a task that took almost a decade of her life. The result, a combination of her artistic talent and a unique printing process, revealed the delicate but hardy beauty found off the beaten path across North America.

__________________________________

Excerpt from Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott, Introduced by Pamela Henson, published by Prestel in association with the Smithsonian Institution (October 4th, 2022). Top image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Pamela Henson

Pamela Henson directs the Institutional History program at Smithsonian Institution Archives and is Historian in Residence, History Department, at American University in Washington, D.C. Recent publications include "Looking at Culture through an Artist's Eyes: William Henry Holmes and the Exploration of Native American Archaeology," in: M. Thomas and A. Harris (eds.), Expeditionary Anthropology: Teamwork, Travel, and the 'Science of Man', 2018. She co-curated Welcome to Your Smithsonian (Smithsonian Castle, 2015). Recent awards include the 2015 Feis Award for Public History, American Historical Association, and Smithsonian Secretary's Gold Medal for Exceptional Service, 2014.