The Traffic Stop: One of the Great Abuses of Police Power in Contemporary Life

Dan Albert on an Obsolete Enforcement Practice That Just Won't Die

In the summer of 2016, Officer Jeronimo Yanez pulled over African-American motorist Philando Castile in a quiet suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota. Castile’s 20-year-old Oldsmobile had a broken taillight but that was a pretext for the stop. Castile fit the description of a robbery suspect because of his “wide-set nose,” Yanez said over the police radio. He asked Castile for his license and insurance. “Sir, I have to tell you I do have a firearm,” Castile said, as he reached into the glove box for his papers. “Don’t reach for it then,” Yanez replied. Castile started to explain that he was reaching for the documents. In the next second or two, Yanez twice told Castile not to pull out the gun and Castile twice told Yanez he was not. Yanez fired seven shots. “I wasn’t reaching,” Castile said again. Those were his last words.

The police shooting of a black man who was not a threat is a story of our times, but there’s another story behind it. In his 14 years of driving, Castile had been pulled over 46 times—including 5 times in the space of 30 days. How police experience drivers during these encounters, and how drivers experience the police shapes public attitudes toward the rule of law. Every case of differential treatment reinforces the American racial divide.

Extensive evidence exists to show that police stop African Americans drivers at a higher rate than they do whites. According to periodic annual surveys by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the traffic stop is the most common encounter people have with the police. These BJS studies show that blacks are more likely than whites to be stopped, to be ticketed, and searched. Most recently, three political scientists collected data on 20 million traffic stops conducted in North Carolina over the course of a decade. Their study, published in 2018, found that blacks are twice as likely as whites to be pulled over and four times more likely to be searched. Furthermore, “… young men of color are clearly targeted for more aggressive treatment.” Such treatment included being removed from their vehicles and having their vehicles searched. In other words, police treat men of color as suspects rather than citizens. That’s certainly how motorist Philando Castile was treated.

In many states, an officer can choose to arrest and jail a driver rather than simply issuing a summons because violations of the vehicle code are criminal (rather than civil) infractions. The Texas Criminal Justice Coalition reviewed all arrests in Harris County, which includes Houston, over the course of 16 weeks. It found that African Americans accounted for nearly half of all drivers arrested on a single, “non-jailable” motor vehicle offense. Blacks make up 20 percent of the Harris County population. Whites, at 70 percent of the population, accounted for only 23 percent of traffic arrests.

In all the conversation about racial profiling of drivers, however, few have questioned the need for traffic stops at all. The legal basis for the traffic stop rests on a bit of thinly sliced logic: the automobile is not dangerous unless it is driven dangerously. In 1906, Xenophone Huddy published the first edition of Law of Automobiles, an authoritative compendium of jurisprudence as it related to motor vehicles. Huddy declared the automobile safer than railroads, “which, owing to their peculiar and dangerous character, are subject to legislation imposing many obligations on them which attach to no others.” In contrast, he found that case law and legislatures said the motor vehicle was not inherently dangerous as long as it was driven properly. In 1911, the Missouri legislature declared that the size and speed of the machine required the “highest degree of care which a very prudent person would exercise.” In the generations following, courts and legislators built upon that simple conclusion.

The heavy traffic accident toll—rising rapidly after World War I—raised public awareness and motivated a response from both the insurance and automobile industries as well from as government. That response came to be known as “The Three E’s: Enforcement, Education, Engineering.” The engineering component meant better roads and better cars. Building new roads took time and cost a lot of money. The automobile’s most obvious inherent danger was its power and speed. But buyers want power and automakers encourage that desire. Indeed, the entire premise of driving, from its earliest days, was the thrill of speed. Like riding a roller coaster, driving a car was just scary enough to be a scream. The automobile was also a fashion statement, so styling took precedence over safety. Education meant drivers ed and safe driving propaganda. Enforcement referred to deterrence policing: convincing drivers that they risked detection and punishment if they violated traffic laws. Also, enforcement required active surveillance because no one could expect the public to report violators.

“That kind of mental anguish is worse than dying, riding for mile after mile, hungry and thirsty, bound and helpless, waiting and not knowing what you’re waiting for. And all over a traffic violation.”

The model for this style of policing came from the contemporaneous attack on vice. During the Progressive Era, reformers enlisted the police to regulate behaviors deemed immoral, ranging from homosexuality and prostitution to intoxication and gambling. Historian David Langum has shown that the Progressives, native-born, white Protestants, felt threatened by changing sexual mores, a rising tide of immigrants, and the dawning “automobile culture.” The hysteria that led to Prohibition in 1919 shifted to traffic safety in the 1930s (incidentally, after the repeal of Prohibition), and it was in this context that modern traffic policing emerged.

Franklin Kreml, a police lieutenant in Evanston, Illinois, developed an aggressive, allegedly scientific, approach to traffic policing, dubbed “selective enforcement.” It targeted locations and behaviors deemed the most dangerous. The police used road blocks to root out drunk drivers and issued “good driver” cards. It is worth noting that Evanston was a dry town and a hotbed of temperance activism. “We couldn’t have gone forward with a program such as this in any place except Evanston,” Kreml recalled. “All of this without any authority of law.”

Several cities adopted the “Evanston Plan” of accident prevention in the 1930s and Northwestern University opened its Traffic Institute with Kreml as its director. Police departments from around the country sent officers to the NUTI for training. Despite its national reputation, data purporting to show that selective enforcement reduced accidents by a factor of two, three, or more, were suspect. As the federal government began taking a more active role in traffic safety during the 1960s, officials began to question the entire link between the traffic stop and safety. The head of the newly formed National Highway Safety Bureau (now NHTSA) “turned his back on the whole program,” Kreml complained.

Yet the traffic stop remains with us. Even if it does reduce such truly dangerous behaviors as driving under the influence and speeding, the safety benefit of many facets of the vehicle code are hard to fathom. California added a ground clearance requirement to its vehicle code in the 1950s. Its target was Chicano lowriders; it remains on the books. Fuzzy dice and air fresheners hanging from the rear view mirror are a no-no in many states. “Failure to signal” may be dangerous (there is little research on the subject) but most drivers fail to signal properly. While taking a break from writing this, I happened to observe four police cruisers, within the space of two minutes and at different locations, fail to signal a left turn. Why then was Sandra Bland, an African-American woman, pulled over on a quiet street near her workplace in the summer of 2015? After handing her a citation for failing to signal properly, state trooper Brian Encina asked Bland if she was agitated and to put out her cigarette. She refused. The situation escalated quickly. Encina aimed his Taser at Bland and yelled, “I will light you up,” before dragging her from the car. He arrested her for resisting arrest. Three days later, unable to arrange bail, Bland was found dead in her jail cell, an apparent suicide.

Legal scholar Barbara Salken has called the traffic code the “general warrant of the 20th century.” The general, or nameless, warrant allows officials to search and detain any subject at will. It became illegal under English common law in the 18th century and the Fourth Amendment forbids its use. But the Supreme Court has rejected appeals to the Fourth Amendment when it comes to driving, citing safety. In 1990, for example, Chief Justice William Rehnquist upheld the right of police to set up sobriety check points, writing, “Drunk drivers cause an annual death toll of over 25,000.” (That figure is highly inflated.) As Officer Jeffrey Coates of the Los Angeles sheriff’s department proudly put it, “There’s a law against almost everything as it relates to a vehicle.” Coates was one of several officers profiled in a New York Times Magazine cover story written following the finding of racial discrimination by New Jersey and Maryland state police along I-95. “They’re going to let the N.A.A.C.P. tell us how to do traffic stops,” complained one Maryland state trooper.

The lopsided treatment of African-American drivers documents an ongoing, perhaps unconscious and endemic racism. But police have also used the general automotive warrant quite deliberately and forcefully in the service of white supremacy. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, African-Americans used carpools to replace lost mobility. Over the course of three days in January, 1956, police issued more than one hundred citations to carpool drivers. Among those carpool drivers was Dr. Martin Luther King, pulled over for doing 30 mph in a 25 mph zone. He was arrested, fingerprinted, photographed, and jailed. When he was arrested again on a traffic charge in 1960, he wrote to his wife Coretta that he had been “chained all the way down to my legs, and they tied my legs to something in the floor so there would be no way for me to escape.” King went on to describe for Coretta the 220-mile bus ride to the Reidsville, Georgia, state prison: “That kind of mental anguish is worse than dying, riding for mile after mile, hungry and thirsty, bound and helpless, waiting and not knowing what you’re waiting for. And all over a traffic violation.”

Because Officer Yanez chose to use deadly force, one simple traffic stop drew national headlines, outrage, and condemnation. Looked at another way though, Philando Castile had escaped death nearly four dozen times over his driving career before being shot. The tragic outcome was not inevitable, but it was made possible by the pretextual traffic stop and the general warrant that applies to us all.

___________________________________________

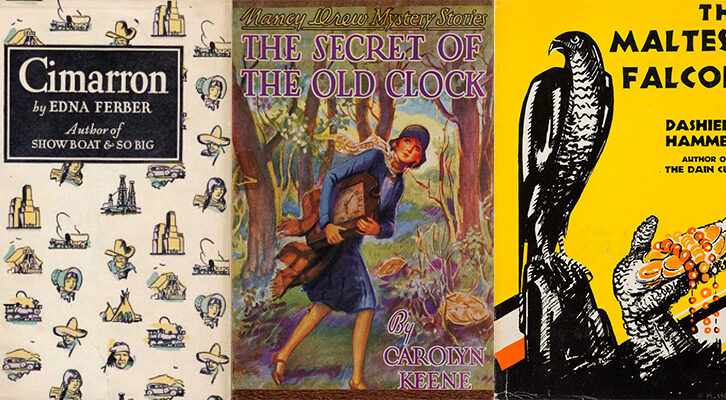

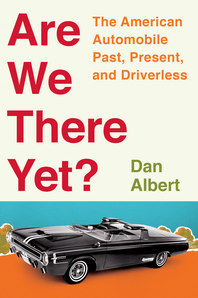

Dan Albert’s latest book, Are We There Yet? is now available from W.W. Norton.

Dan Albert

Dan Albert holds a PhD in history from the University of Michigan. He writes about the past, present, and future of cars for n + 1 magazine.