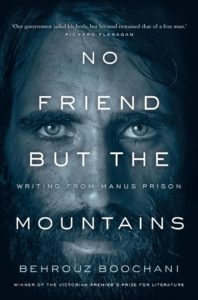

No Friend But the Mountains is a book that can rightly take its place on the shelf of world prison literature, alongside such diverse works as Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, Ray Parkin’s Into the Smother, Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died, and Martin Luther King Jr’s Letter from Birmingham Jail.

Written in Farsi by a young Kurdish poet, Behrouz Boochani, in situations of prolonged duress, torment, and suffering, the very existence of this book is a miracle of courage and creative tenacity. It was written not on paper or a computer, but thumbed on a phone and smuggled out of Manus Island in the form of thousands of text messages.

We should recognize the extent of Behrouz Boochani’s achievement by first acknowledging the difficulty of its creation, the near impossibility of its existence. Everything has been done by our government to dehumanize asylum seekers. Their names and their stories are kept from us. On Nauru and Manus Island, they live in a zoo of cruelty. Their lives are stripped of meaning.

These prisoners were all people who had been imprisoned without charge, without conviction, and without sentence. It is a particularly Kafkaesque fate that frequently has the cruelest effect—and one fully intended by their Australian jailers—of destroying hope.

Thus the cry for freedom was transmuted into charring flesh as 23-year-old Omid Masoumali burnt his body in protest. The screams of 21-year-old Hodan Yasin as she too set herself alight.

This is what we, Australia, have become.

The ignored begging of a woman on Nauru being raped.

A girl who sewed her lips together.

A child refugee who stitched a heart into their hand and didn’t know why.

Behrouz Boochani’s revolt took a different form. For the one thing that his jailers could not destroy in Behrouz Boochani was his belief in words: their beauty, their necessity, their possibility, their liberating power.

And so over the course of his imprisonment Behrouz Boochani began one of the more remarkable careers in Australian journalism: reporting about what was happening on Manus Island in the form of tweets, texts, phone videos, calls, and emails. In so doing he defied the Australian government which went to extreme lengths to prevent refugees’ stories being told, constantly seeking to deny journalists access to Manus Island and Nauru; going so far, for a time, as to legislate the draconian section 42 of the Australian Border Force Act, which allowed for the jailing for two years of any doctors or social workers who bore public witness to children beaten or sexually abused, to acts of rape or cruelty.

His words came to be read around the world, to be heard across the oceans and over the shrill cries of the legions of paid propagandists. With only the truth on his side and a phone in his hand, one imprisoned refugee alerted the world to Australia’s great crime.

Behrouz Boochani has now written a strange and terrible book chronicling his fate as a young man who has spent five years on Manus Island as a prisoner of the Australian government’s refugee policies—policies in which both our major parties have publicly competed in cruelty.

Reading No Friend but the Mountains is difficult for any Australian. We pride ourselves on decency, kindness, generosity, and a fair go. None of these qualities are evident in Boochani’s account of hunger, squalor, beatings, suicide and murder.

Australia imprisoned his body, but his soul remained that of a free man. His words have now irrevocably become our words, and our history must henceforth account for his story.I was painfully reminded in his descriptions of the Australian officials’ behavior on Manus of my father’s descriptions of the Japanese commanders’ behavior in the POW camps where he and fellow Australian POWs suffered so much.

What has become of us when it is we who now commit such crimes?

This account demands a reckoning. Someone must answer for these crimes. Because if they don’t, the one certainty that history teaches us is that the injustice of Manus Island and Nauru will one day be repeated on a larger, grander, and infinitely more tragic scale in Australia.

Someone is responsible, and it is they, and not the innocent, to whose great suffering this book bears such disturbing witness, who should be in jail.

This book, though, is something greater than just a J’accuse. It is a profound victory for a young poet who showed us all how much words can still matter. Australia imprisoned his body, but his soul remained that of a free man. His words have now irrevocably become our words, and our history must henceforth account for his story.

I hope one day to welcome Behrouz Boochani to Australia as what I believe he has shown himself to be in these pages. A writer. A great Australian writer.

–Richard Flanagan, 2018

*

Queuing as Torture: Manus Prison Logic / The Happy Cow

A twisted, interlocking chain of hungry men

Bodies mutate under the burning sun

Heads in an oven red by the sun

Undergoing sickening transformations

A long line of men of different heights, weights, ages and colours.

Days in the prison begin with the commotion of long queues—long, pulverizing queues. Hungry prisoners rush out of their sweaty, sticky beds early in the morning, and like bees they swarm the tent that makes up the dining area. In this instance, hungry actually means starving. Once dinner is over, no one can find anything else to eat. In the dead of night, the smell of hunger wafts through the entire prison. No one is allowed to take even one potato from the dining area. Anything that can be eaten has to be eaten right there under the tent. It is the last chance to fill their stomachs, stomachs that take over from the mind, stomachs with full authority over the body.

Human agency is subdued by the number five.At the front of the dining area always stand a few grim and brainless G4S guards. They focus their gaze in a way that feels like a stop-and-search on anyone who exits the tent. If a pocket shows the slightest bulge, the guards order a Papu to frisk the prisoner. Part of the strategy to totally control the body. The Papu shakes his head in disapproval while he searches all the pockets, the lower legs, the torso and then under the arms. At times this activity results in the discovery of a single potato or a crushed piece of meat. When the Papus find something, they pick it up as if it has come out of the rubbish bin. The Australian G4S guard reminds the prisoner again: “Taking food out is against the rules.”

Young men stand in the sun for hours, queuing for dirty, poor-quality food. The meat is like pieces of car tire. Jaws struggle to chew the badly cooked meat.

The prisoners are aware that at the start of the queue in front of the tent, a few G4S guys sit on chairs and order groups of five to enter the dining area. The Manus Prison Logic is about domination.

Domination: five people need to leave the dining area so that five people can take their places. The community has to wait until five people leave, and then the officer can control the next five with his finger, giving permission to enter. We are like puppets on a string, put in motion with the flick of a finger. Every mind is caught up in a process, a process that has become normalized. A domesticating process.

The officer himself doesn’t have any autonomy or control over his own fingers, not even over the way he chooses to sit. Everything is micromanaged and mechanical. The prison regulates the quantities of things and limits the time. A totally mechanical and prescriptive process has been put in place:

The logic of five

Five people follow on from five people

Then the officer turns to five people on their way out

Next, five people

The automated finger signals five people

Another five enter

Five people to replace five people

Five enter, sitting on five chairs at the beginning of the queue

The number five

Five chairs

Five chairs prepared at the beginning of the queue

The rest wait, standing in line

Everything is reduced to the number five.

Sometimes the officer in charge of entry, instead of signaling with a single finger, signals with all five fingers.

Human agency is subdued by the number five.

The queue is a replica of a factory production line. Total discipline. Calculated and precise. The first stage is at the end of the line—a place covered by an awning, a place from which no one can tell where the queue ends. The queue makes a turn behind the rooms occupied by Sri Lankans. After at least half an hour, one arrives at the bend and realizes that the queue extends for another 30 meters.

The desire for food causes people to push towards the front, extremely hungry people just reacting instinctively. Bodies are grafted together here, much more than in other queues.Five individuals with full stomachs

Five individuals leave the tent

Again, the logic of five.

The queues are a series of trucks loading up as they work inside a fiery excavation site, inside the inferno of a strip-mining pit. Empty, then full.

At the bend, hungry prisoners experience a mix of significant emotions. Joy and pain, hope and hopelessness. Arriving at the bend is an achievement, but the prisoner leaves the shelter of the shade and enters the section under the burning sun. This means preparing to face the sun, a sun that penetrates each cell with its stinging rays. Like thousands of hot needles pricking into thousands of interconnected spots. Witnessing the queue from the point at the head of the bend reminds the prisoner of the difficult path still to be endured.

Arriving at the bend, however, evokes a little feeling of celebration, a little feeling of hope. The prisoner realizes that he is there, realizes that position right there and then, realizes that the stage involving the bend has passed. He is one stage closer to food. A 30-meter trip ahead, but now the the prisoner has no choice but to move along, stuck to the wall.

The queue forms parallel to the wall, in total sun. Hot and merciless. But there is a small overhang that stretches out to cover a medium-sized person’s shoulders. It projects a narrow shadow just over the heads of the prisoners. The prisoners are forced to protect themselves from the heat of the sun by moving up close against the wall. In this position, if they move a little, the sun will bear down on their bare heads and necks. Parts of the shoulders are still exposed to direct sunlight, still exiled across the other side of the border of sun and shade.

The problem doesn’t end here because the queue forms over a concrete surface of 30 centimeters, a surface that stands half a meter above ground level. It looks like a step positioned high and extended, a step on which the prisoners climb, standing up there, stuck up against the wall. A high, extended step, 30 centimeters wide, half a meter high, with groups of men standing on top. Fear of the sun’s heat, scrambling just to stand there under a narrow piece of shade—this causes the queue to form straighter than any other. Other queues, in other places, outside the prison, form like a chain, loose and lax, possibly a small curve, possibly a large curve. But this part of the queue takes the form of a straight line. The queue is cramped. The desire for food causes people to push towards the front, extremely hungry people just reacting instinctively. Bodies are grafted together here, much more than in other queues.

Groups of men are up against the wall

Groups of men are embedded into the wall

The spectacle of the prison queue is a raw and palpable reinforcement of torture.

Throughout the line a few G4S guards supervise. These G4S guys are distinctive, unlike the others at the front of the line or those with other duties in the tent. These few people stand in the shade of two tanks of water opposite the queue. They do nothing but stare at the queue, a queue moulded into the wall. They do absolutely nothing. The purpose of their presence is simple: to announce that the queue has a master. They are like shepherds guiding a herd of sheep down an obvious path, a path they are following anyway. At times the guards take notes in their little pads, probably out of habit. Or they communicate through their walkie-talkies. However, some of their actions are relatively kind. For instance, there are times when one of them carts a box of bottled water from the dining area and places it next to the queue. The bottles of water have become so warm that drinking them troubles the stomach.

There’s a massive difference between someone who simply lies in words and someone who lies convincingly. Those individuals work their bodies to convey impressions.At the same time, there are always those among us who are like stray dogs looking to pounce and steal a piece of meat; they try to jump to the front of the queue from behind the tanks. They have a strong sense for this kind of skillful leap and know exactly when to execute it, at a time when few will notice. Even if people notice, they are so quick that there is no chance, for instance, that someone at the end of the queue could recognize them—or, in any case, have the opportunity to register and recollect. The direction of the leap is calculated. It is carried out so the face remains anonymous. From the end of the queue, they appear to be phantoms—dark figures that pass by for just one moment.

The leap occurs in a spot at the head of the queue. Like hopping up on the rung of a ladder. When the leap is performed successfully, the perpetrator stands up in a way that signals that nothing out of the ordinary has occurred. The shoulders, the face, look exactly like everyone else in the queue. This is an outright deception. It requires artistry.

There’s a massive difference between someone who simply lies in words and someone who lies convincingly. Those individuals work their bodies to convey impressions, for example: “I’m just so exhausted,” or, for instance, “That sun is such a bastard” or “What a long line,” or “Oh god, I’m exhausted, I’ve been waiting in this queue for ages.”

These guys are so skillful that one can hardly tell the difference between them and the others who have been standing under the sun for a long period. And separating them from the queue usually results in physical conflict. They don’t respond to verbal protest, so someone needs to approach them at the front of the line, identify them, and then kick or punch them out of the line. For a prisoner standing upright and already exhausted, engaging in such an act requires double the energy. Every now and then it ends up in a brawl.

Interestingly, most conflicts end without interference by G4S guards. A bit of swearing and some harmless kicking and punching, and the whole thing is over in a few short minutes.

One interesting point is that the violators themselves also accept that they are low-lifes and immature individuals, juveniles with no honor.

It’s bizarre how their personalities are reduced to gluttonous pack animals.Behaving like a juvenile is a successful way to acquire food quickly. there are others who get food to their mouths, but are respectful and just in doing it. These people wait hours before the food is distributed. They occupy the head of the queue, the starting point of the line. The only superior quality they have over others is their ability to wait for hours on end with their chunky asses, wait for hours without moving, sitting on stiff chairs or standing in the sun. They are people with nerves of steel, indifferent as mules.

Imagining this is difficult: how can a human stay put and wait for hours without leaving that spot? How can he just stay there, not moving an inch? I always imagine them with the features and forms of domestic animals. It’s bizarre how their personalities are reduced to gluttonous pack animals. The personality of each one reflects heritage with the mule; it is all over their faces, no integrity, no dignity. Cows. Greedy and gluttonous cows. Leeches. Hanging like leeches. Behaving like professional beggars.

I admit that I don’t feel comfortable with their presence in the prison. I see them ahead of me and a desire for violence erupts inside me. If I had more confidence in my muscles I might make my way through to the front of the line to beat them up. It isn’t as if I am scared to fight with those who stand way down the front of the queue. No. It just isn’t worth the trouble. Also, I am sure I don’t have the strength necessary to sort things out, to assert myself, to completely beat them down.

So instead I imagine a man with powerful muscles. Calm and collected, he steps from the queue and announces to all the men that he will be enforcing justice. The men—even those at the front of the queue—look on with curiosity.

But this performance is not for them. Not even for The Mules. It is designed to grab the attention of the officers standing in the shade of the tanks. They huddle together, looking on keenly. I imagine the powerful man walking purposefully to the front of the queue. His strut entices and intensifies the curiosity of the onlookers. When he reaches the front of the queue, The Mules stare at him with confusion.

The officers by the tanks start to relax, reassured that they are not the target. Their huddle loosens. Yet all focus remains on the powerful man. Suddenly he takes the neck of the first person in the queue. And lifts him off the ground. Then, with one well-placed kick, he sends the first Mule flying to land behind the tanks. The powerful man works his way through the line methodically, casting out individuals one after another . . .

But this is just a fantasy, something I draw from the depths of my hungry guts. I am no such powerful man. I accept that the other men are heftier than me. I accept that they are thieves who have taken everything from me. At times, my imagination even makes them out to be lions, whereas I’m a lowly fox, frail and weak, waiting to scavenge their leftovers.

–Translated from the Farsi by Omid Tofighian.

__________________________________

This excerpt is taken from No Friend but the Mountains, text copyright © 2018 by Behrouz Boochani, translation copyright © 2018 by Omid Tofighian. Reproduced with permission from House of Anansi Press, Toronto.