The Top 10 Pieces of Doubleday’s Publishing History Slated for Auction

Looking at the Legacy of a Great American Publishing Family

Doubleday is one of the eponymous publishing houses that dominated 20th-century American literary culture. From its founding in 1897 through various mergers and its eventual sale to Bertelsmann, it has thrived. Even today, nestled within Penguin Random House, the Doubleday brand-name lives on, the dream of Frank Nelson (F. N.) Doubleday, a Brooklyn boy who had billed himself as a “Book and Job Printer” by the tender age of 12.

Now some of the company’s legacy is for sale. Coming to auction in New York tomorrow, January 11, is the estate of Nelson Doubleday Jr., the third and last of the Doubledays to run the company. Nelson Jr., who died in 2015, sold his stake in 1986, the same year the Mets, a team he co-owned, won the World Series. The sale of his belongings beckons us to page through the publisher’s past, one literary lot at a time. It also presents “a great opportunity to own a piece of one of New York’s great publishers,” said Peter Costanzo, vice president at Doyle auction house.

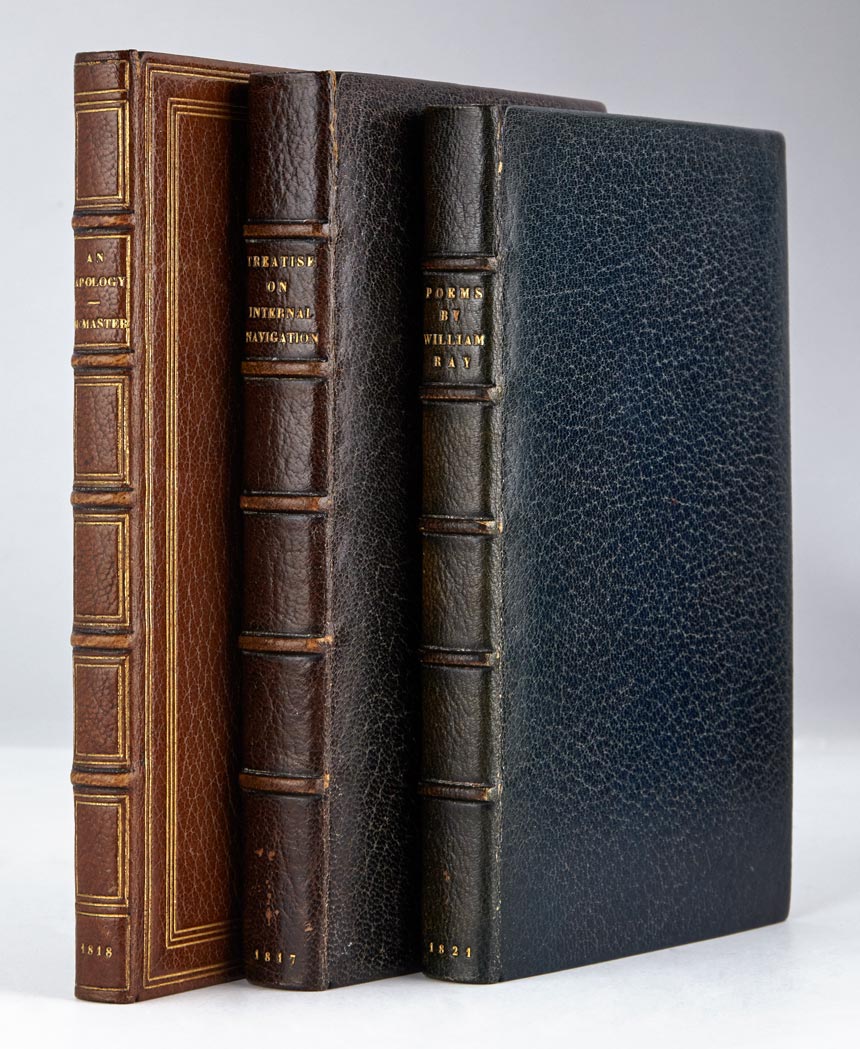

First off, F.N. Doubleday (1862-1934), founded the firm, but he was not the first Doubleday with ink in his veins. Uncovered in the Long Island library of Nelson Jr. were these three volumes, rebound in leather, published by distant relative Ulysses F. Doubleday between 1817-1821 in upstate New York. The riveting titles include Treatise on Internal Navigation, An Apology for the Book of Psalms, and William Ray’s Poems on Various Subjects. Ulysses, however, gave up publishing for politics and became a member of the House of Representatives in 1831.

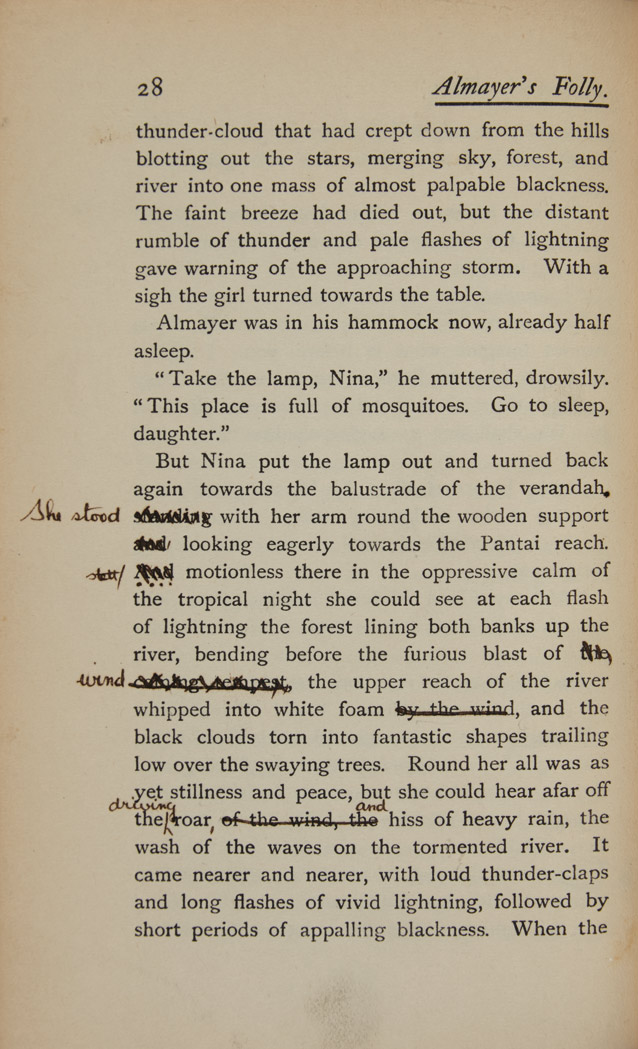

Joseph Conrad is one of the headliners of this auction. There are seven distinct lots of his books, all of which are significant in some way—limited editions, signed editions, deluxe presentation copies, etc.—but this one still stands out. It is an 1895 edition of Almayer’s Folly, one of the author’s earliest books, which he annotated in pen for F.N. in anticipation of the “definitive” 26-volume edition of Conrad’s complete works that Doubleday published in the 1920s. F.N. was a great fan and patron of Conrad, and he took care to have this book sumptuously rebound and retained in his private library.

This “association copy,” as they say in book collecting circles, of Theodore Low De Vinne’s The Invention of Printing, is inscribed to F.N. Doubleday in 1898. De Vinne was a New York printer noted for his dedication to the craft of fine bookmaking—with eight other bibliophiles, he co-founded the Grolier Club. When Doubleday struck out on his own in 1897, he reports in his Memoirs of a Publisher, he sought De Vinne & Co., “who were regarded as the most distinguished and perhaps the most expensive printers in New York, to make our books. They did good work, and I think helped us considerably in our start.”

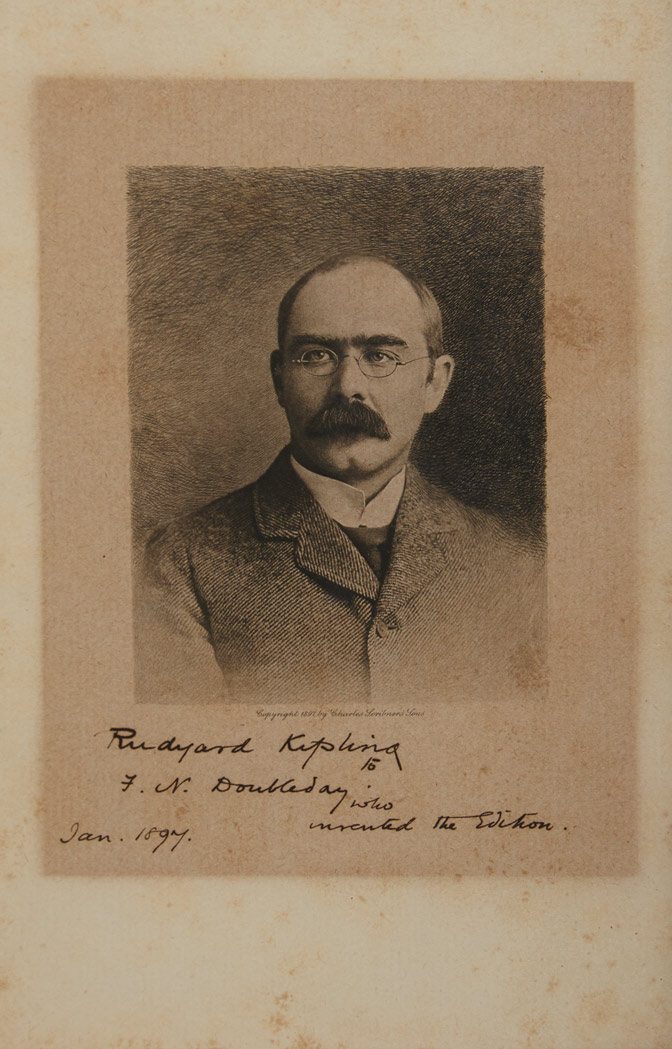

Rudyard Kipling was, arguably, the most important author in Doubleday’s history. But first he belonged to Scribner’s, as did F.N. Doubleday, who started working for Charles Scribner at the age of 14 and stayed with him for 18 years. Toward the end of his tenure there, Doubleday pitched the idea of creating a “uniform set” of Kipling’s works. No one encouraged him; when Doubleday took the train up to Vermont to see the author in person, Kipling told him, “It is a fine scheme, but you can never work it out.” But Doubleday came through, and this multi-volume set, called the “Outward Bound edition,” is the result. In this particular copy, Kipling inscribed under the portrait, “Rudyard Kipling to F.N. Doubleday who invented this edition. Jan. 1897.” The project initiated a longtime friendship, according to Doyle’s Peter Costanzo. “I think it’s what really launched Doubleday, it gave him the moxie to go into publishing by himself,” he added.

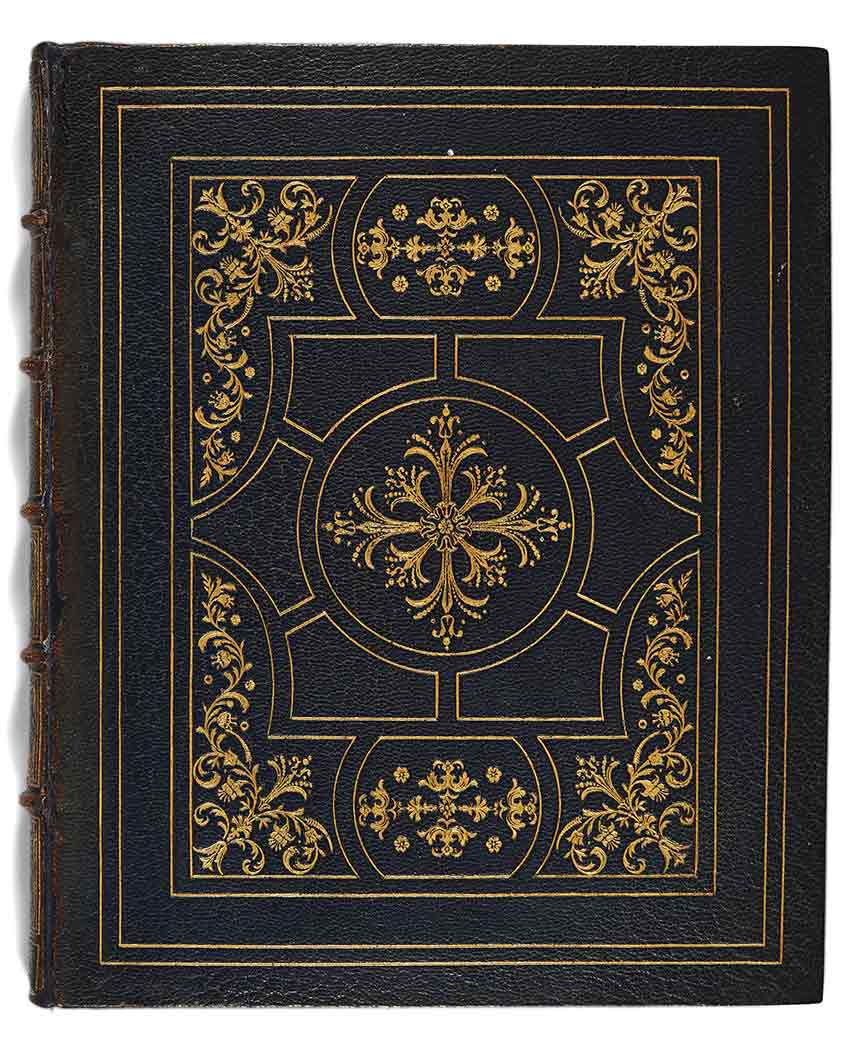

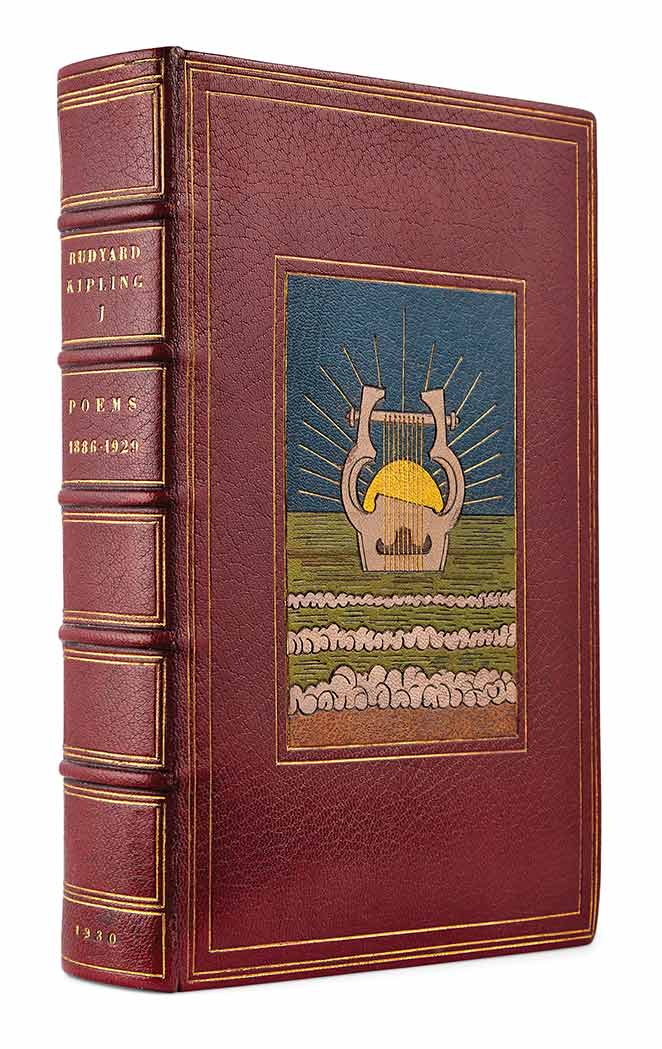

Kipling and Doubleday were indeed steadfast pals, referring to each other as “Rud” and “Effendi” (Kipling’s nickname for F.N., supposedly a mash-up of his initials and the “Turkish or Arab name for Chief,” Doubleday writes). So there are several examples of finely bound and gilt-decorated Kipling books, bound by Doubleday’s in-house bookbinders, The French Binders, whose output he described as “the cream of all the fine binding work done in this country.” This one is a first edition of Kipling’s Poems 1886-1929, copy number 3 of 12 presentation sets bearing the author’s signature and bookplate. The morocco leather binding and watered silk endpapers suggest just how much Kipling meant to his publisher.

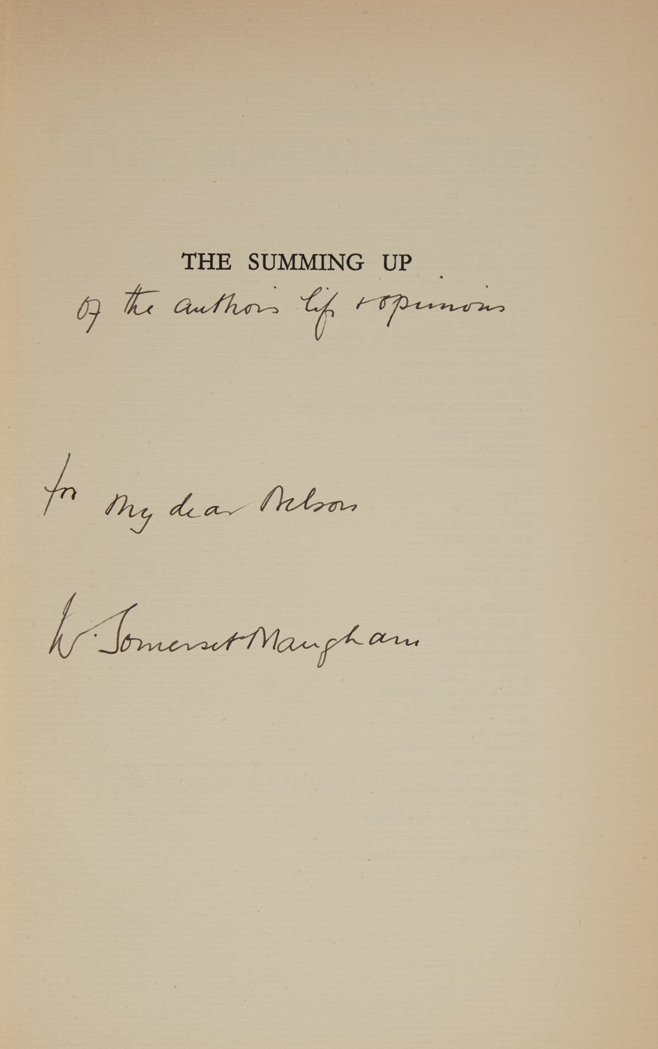

Along with Conrad and Kipling, the British playwright and novelist W. Somerset Maugham was another Doubleday staple. This is a collection of Maugham’s English first editions presented by the author to “my dear Nelson” (F.N.’s son and the company’s next leader) paired with three signed limited editions published by Doubleday, including copy number one of Cakes and Ale. According to the auction catalog, “While the Doubleday family began publishing Maugham’s work in America as early as 1915, it was after the company purchased a controlling stake in 1921 of William Heinemann’s English publishing house that their relationship with Maugham was cemented.”

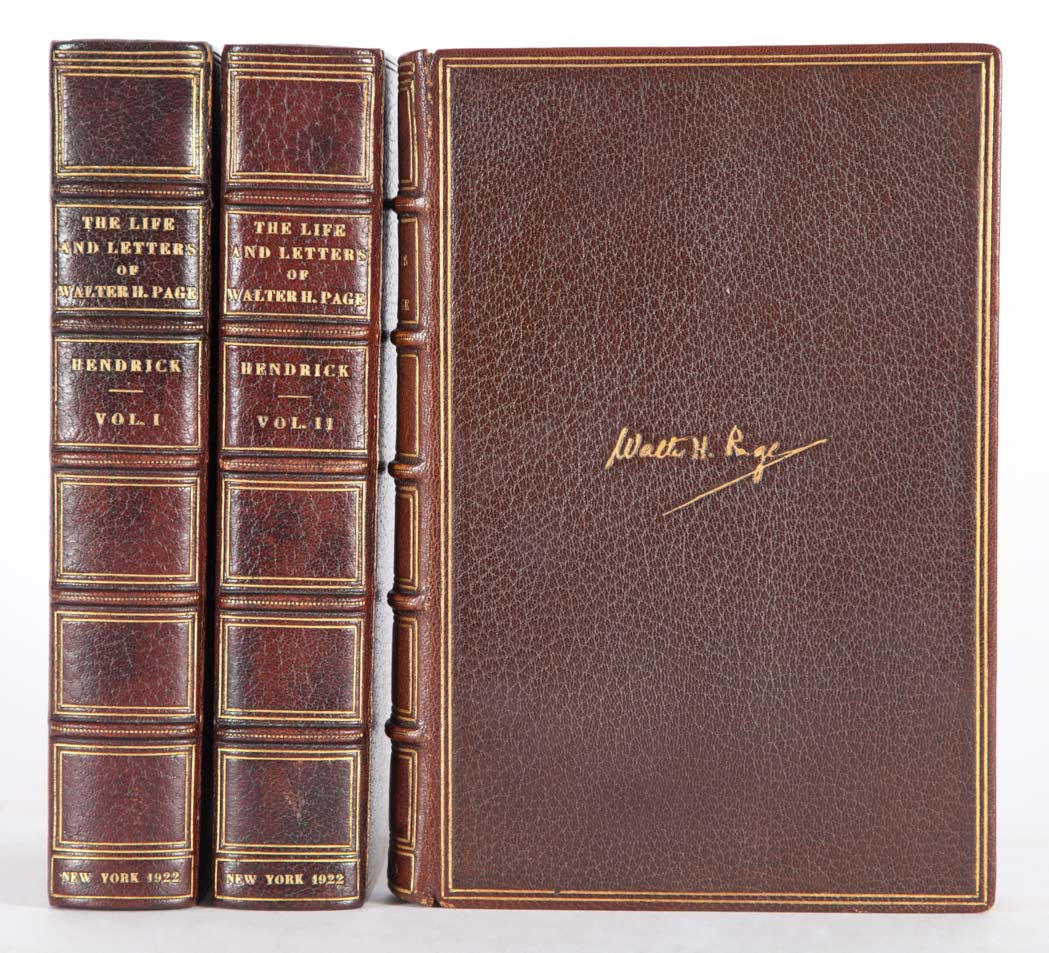

F.N. Doubleday encouraged publishing partnerships and, over the years, he joined forces with Samuel McClure, George H. Doran, and Walter Page, who left his job as editor of the Atlantic Monthly to form Doubleday, Page & Co. in 1900. That F.N. kept this three-volume set of The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page (1922), copy 2 of 377 printed, bound in burgundy morocco, reads as a tribute to his colleague, whom he once described as “a delightful man to work with.” That association between two key publishing bigwigs “resonates with collectors,” said Costanzo. “Walter Page is largely forgotten, but was very important in his day.”

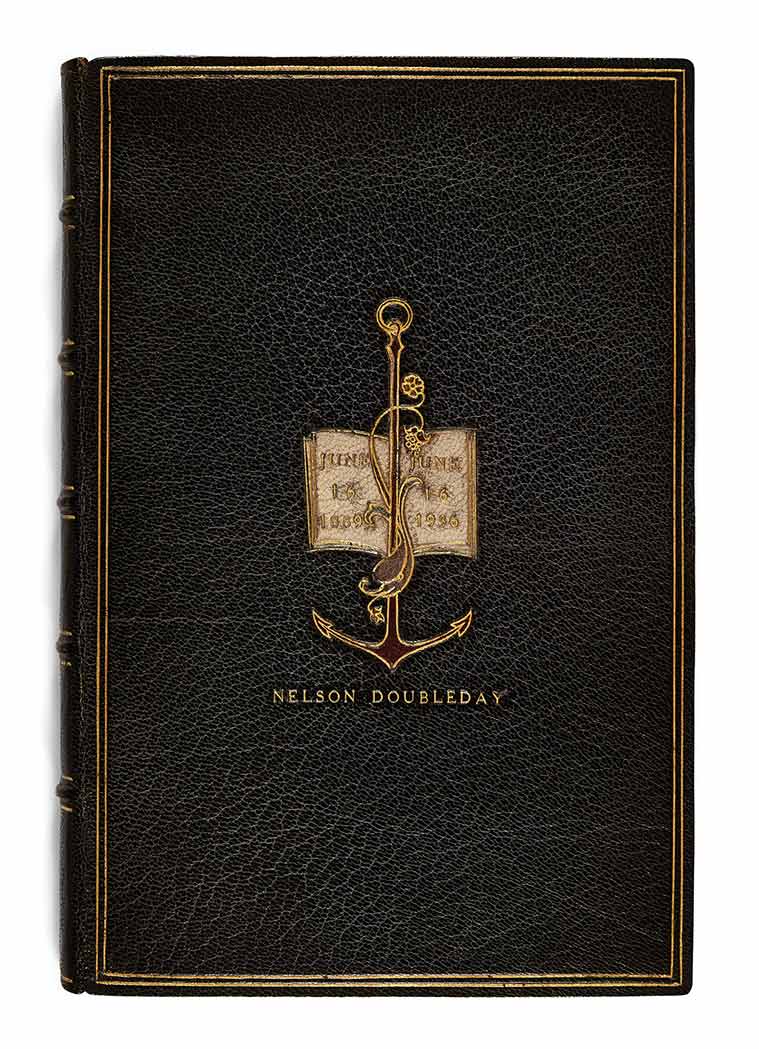

Lot 96 contains the most striking and intimate pieces of corporate history: a selection of commemorative items, including anniversary albums decorated in gilt with the company’s dolphin and anchor mark; an illuminated manuscript page memorializing the death of F.N. in 1934, and another honoring Nelson only fifteen years later; a bronze bust of “Effendi;” a tribute to Theodore Roosevelt Jr., who worked for the firm until his death; and various letters to Mrs. Doubleday from notable authors. In his memoir, F.N. recalls the earliest album in this group, from the company’s jubilee in 1922, having been signed “by every member of staff.”

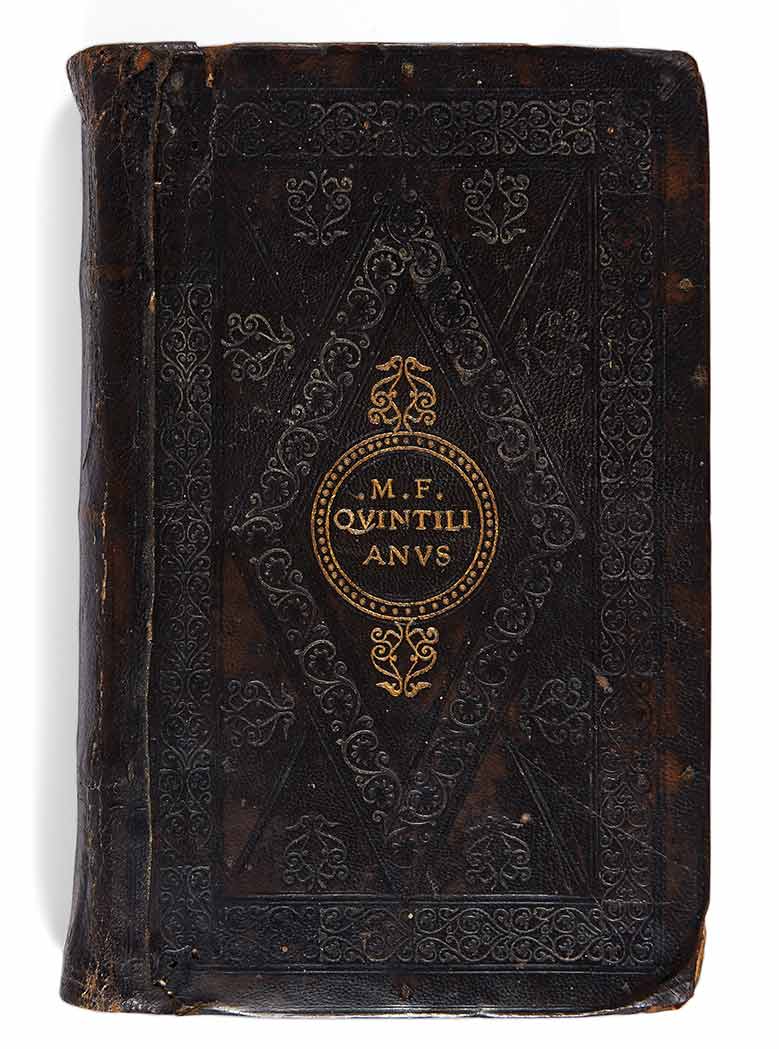

Speaking of that dolphin and anchor printer’s device, aka logo or colophon, as it is sometimes mistakenly called, this 500-year-old book was a gift from Russell Doubleday to his brother, F.N. Why? Because Doubleday famously appropriated that dolphin and anchor from Venetian printer Aldus Manutius (1449-1515). Russell further embellished this worn and heavily annotated copy of De Instituione Oratoria with an inscription to F.N. and a photograph of the site of Aldus’s Aldine Press. F.N. obviously cherished the ancient symbol; in the afterword to F.N.’s memoir, Christopher Morley writes of a sundial in the same design gracing Doubleday’s legendary Garden City publishing campus.

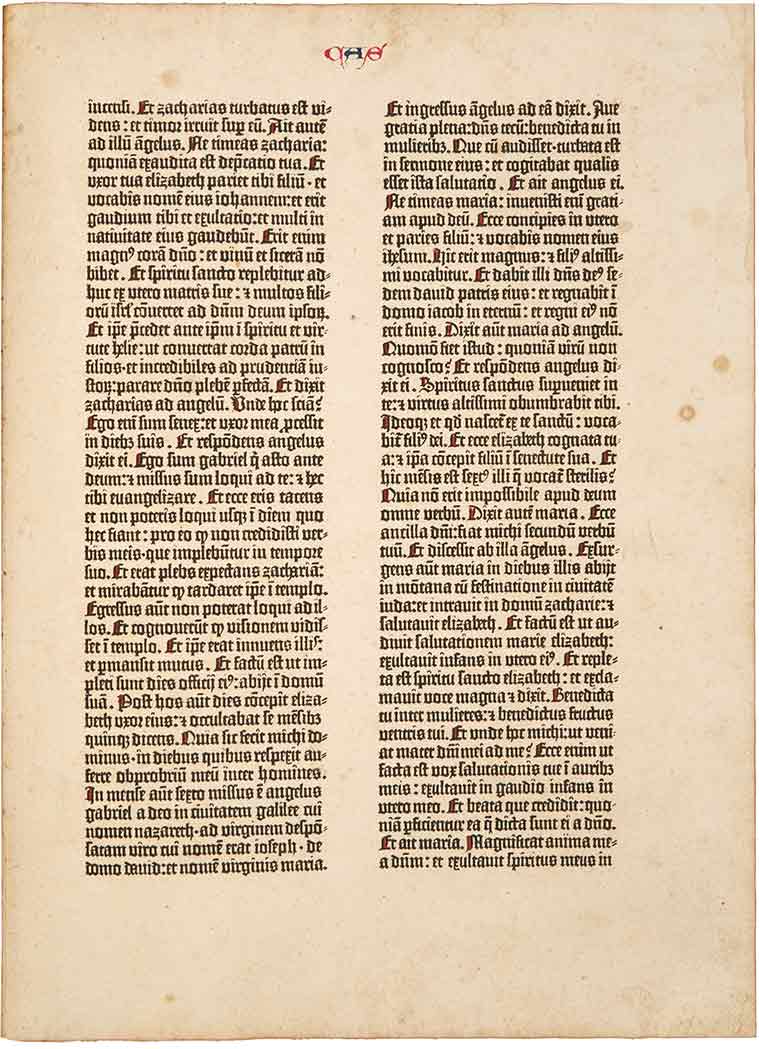

Going back even further than Aldus, Nelson Doubleday owned a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible. Like his father—and rather unlike his son—Nelson was a bibliophile, and he affixed his bookplate to this treasure, effecting a material connection between one eminent publisher and another. It’s likely, said Costanzo, that Doubleday would have purchased this “Noble Fragment” in 1921, when a book dealer named Gabriel Wells began peddling individual leaves in morocco slipcases to collectors for $150 each—“less a heresy in 1921 than this seems today,” notes the auction catalog alongside today’s value: $40,000-60,000. Doubleday’s leaf, from the Gospel of Luke, records the nativity scene. “It’s hard to imagine a more important leaf in the Bible,” Costanzo said.

Rebecca Rego Barry

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places and the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine. On Twitter @rrb_writer.