The Time Murakami Met Carver (and Other Literary Meet-Cutes)

Famous Writers in the Wild, Talking to Each Other

The best definition of a meet-cute I’ve ever heard comes from classic and important film The Holiday: “Say a man and a woman both need something to sleep in, and they both go to the same men’s pajama department, and the man says to the salesman, ‘I just need bottoms.’ The woman says, ‘I just need a top.’ They look at each other, and that’s the meet-cute.” All together now: awww.

Now, to be quite honest, most of these meets are quite a bit less cute than that. After all, they happened in real life, not in the movies, and they happened to writers, who are not renowned for their extreme cuteness. But many writers have had momentous—or deliciously disappointing—first meetings with one another, and several of these are interesting enough to bear repeating—perhaps at your next cocktail party, while trying to drum up some cute meetage of your own. Below, a few favorites—gossip on in the comments, if you so desire.

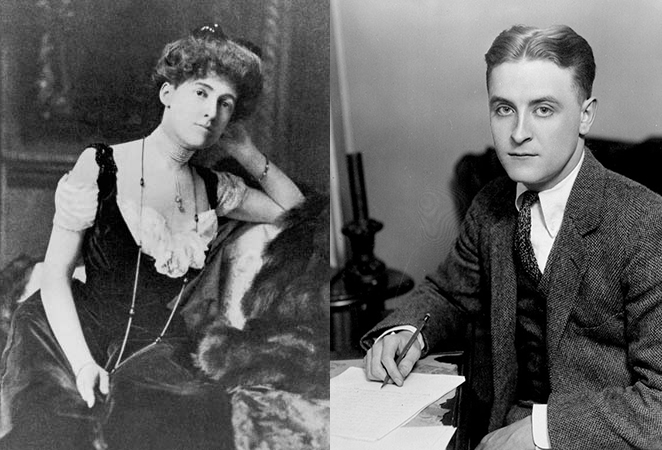

Edith Wharton + F. Scott Fitzgerald

In 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald sent Edith Wharton, then in her sixties, a copy of his newly-published novel The Great Gatsby. She responded with a letter. “I am touched at your sending me a copy,” she wrote, “for I feel that to your generation, which has taken such a flying leap into the future, I must represent the literary equivalent of tufted furniture and gas chandeliers.” She praised the book, and invited Fitzgerald and Zelda to come up for tea or lunch.

Apparently, Zelda refused, feeling that she would be made to “feel provincial,” and so Fitz went with Teddy Chanler, a mutual friend of he and Wharton’s. But first, obviously, he got drunk. Quite drunk. According to Arthur Mizener’s account of the tea, Fitzgerald first insulted Wharton, then tried to shock her and her other fancy guests with a story about he and Zelda living for two weeks in a bordello. Wharton was not shocked. “But Mr. Fitzgerald,” she said when he began to lose his nerve, “you haven’t told us what they did in the bordello.”

Later, Wharton dashed off an entry in her diary: “To tea, Teddy Chanler and Scott Fitzgerald, the novelist—awful.”

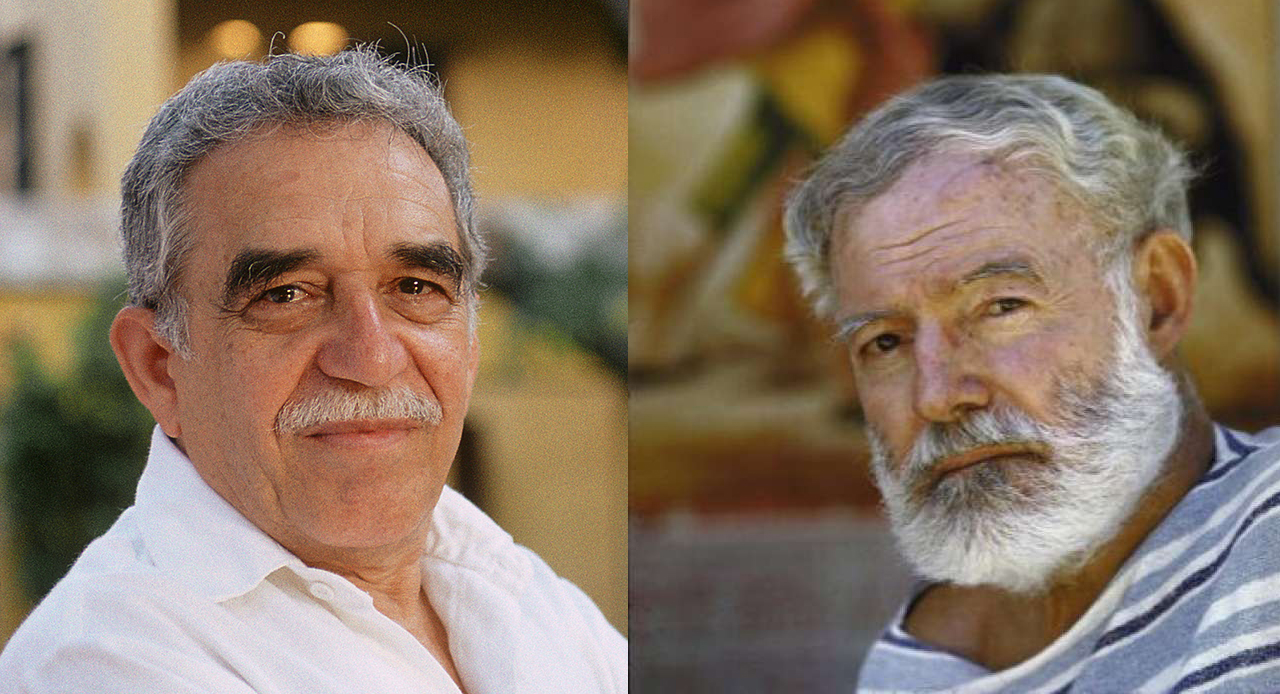

Gabriel García Márquez + Ernest Hemingway

When Gabriel García Márquez was 28, he saw Ernest Hemingway on the street in Paris. I’ll let him tell the rest:

I recognized him immediately, passing with his wife Mary Welsh on the Boulevard St. Michel in Paris one rainy spring day in 1957. He walked on the other side of the street, in the direction of the Luxembourg Gardens, wearing a very worn pair of cowboy pants, a plaid shirt and a ballplayer’s cap. The only thing that didn’t look as if it belonged to him was a pair of metal-rimmed glasses, tiny and round, which gave him a premature grandfatherly air. He had turned 59, and he was large and almost too visible, but he didn’t give the impression of brutal strength that he undoubtedly wished to, because his hips were narrow and his legs looked a little emaciated above his coarse lumberjack shoes. He looked so alive amid the secondhand bookstalls and the youthful torrent from the Sorbonne that it was impossible to imagine he had but four years left to live.

For a fraction of a second, as always seemed to be the case, I found myself divided between my two competing roles. I didn’t know whether to ask him for an interview or cross the avenue to express my unqualified admiration for him. But with either proposition, I faced the same great inconvenience. At the time, I spoke the same rudimentary English that I still speak now, and I wasn’t very sure about his bullfighter’s Spanish. And so I didn’t do either of the things that could have spoiled that moment, but instead cupped both hands over my mouth and, like Tarzan in the jungle, yelled from one sidewalk to the other: ”Maaaeeestro!” Ernest Hemingway understood that there could be no other master amid the multitude of students, and he turned, raised his hand and shouted to me in Castillian in a very childish voice, ”Adiooos, amigo!” It was the only time I saw him.

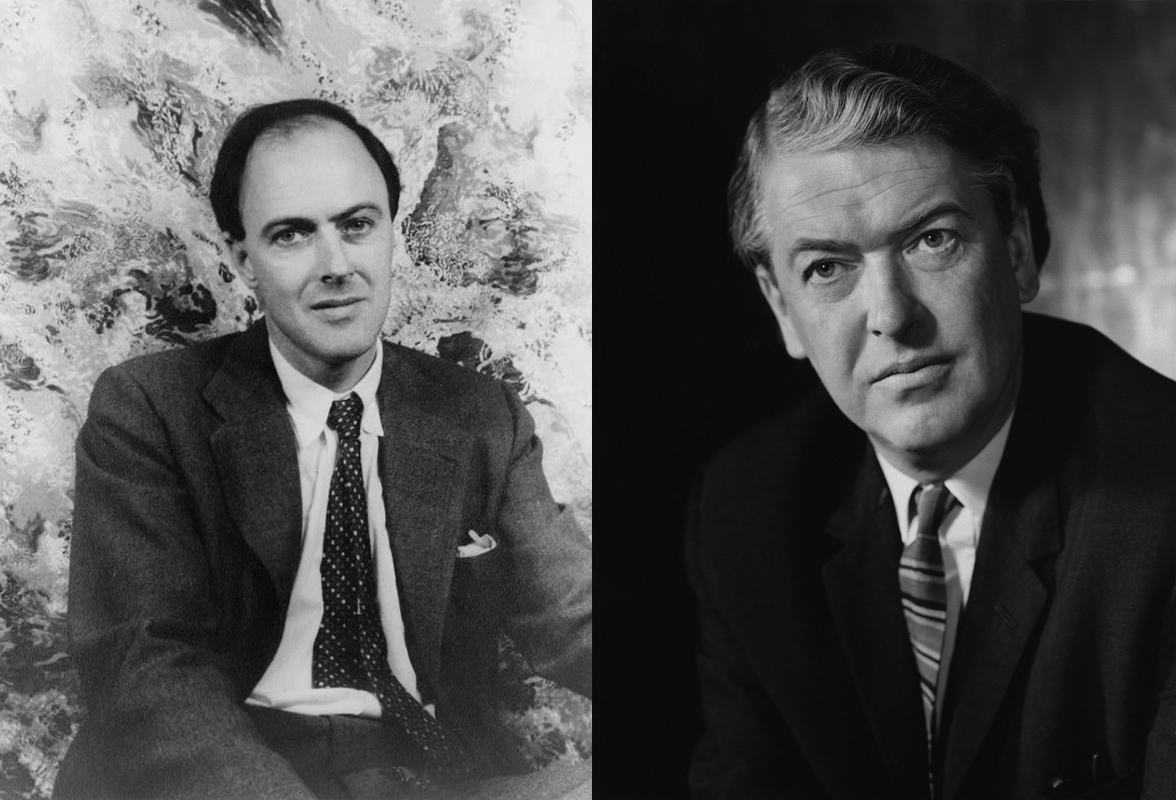

Roald Dahl + Kingsley Amis

Roald Dahl and Kingsley Amis met at a party thrown by Tom Stoppard in 1972, and they did not get along. Apparently, Dahl immediately began talking about money, and suggested to Amis that if he really wanted to make the big bucks as a writer, that he should try his hand at writing books for children. The tension was palpable. Donald Sturrock, Dahl’s biographer, wrote that “Amis, who had no interest in children’s fiction, felt he was being patronized by Dahl’s suggestion that his own writing was not bringing him enough money. Dahl, for his part, was in precisely the kind of English literary environment he loathed. He knew that Amis, like most of the guests, did not respect children’s writing as proper literature and this attitude made him feel vulnerable.”

According to his memoirs, Amis demurred, “I’ve got no feeling for that kind of thing,” and Dahl retorted, “Never mind, the little bastards’d swallow it,” before jumping into his helicopter and leaving the scene. “I watched the television news that night,” Amis writes, “but there was no report of a famous children’s author being killed in a helicopter crash.”

Nell Zink + Jonathan Franzen

This is a digital meet-cute but it’s a good one. As you probably know, Jonathan Franzen loves birds. Luckily for readers, Nell Zink also loves birds. As Kathryn Schulz tells it in The New Yorker:

In July of 2010, Jonathan Franzen published an article in this magazine on the illegal hunting of songbirds in the Mediterranean. Six months later, he received a two-page, single-spaced, typewritten letter postmarked Reutlingen, Germany. “Dear Mr. Franzen,” it began, “I recently translated Martin Schneider-Jacoby’s birding guide to the wetlands of the western Balkans.” The letter, which went on to describe the plight of birds in that region, was simultaneously erudite, colloquial, mocking, and sincere; it contained a reference to Pierre Bourdieu’s “Les Règles de l’Art,” an aside on the Balkan war, an untranslated passage in German, armed Italians, alarmed park rangers, great bustards, spotted crakes, “ditch” used as a verb, and the phrase “fucking it up.” The author expressed the conviction that Franzen would do his part for the birds of the Balkans, because “you love them for what they are (tiny little displaced persons).” Very truly yours, the letter concluded, Nell Zink.

Franzen laughs when he talks about the letter, a laugh of bemused appreciation that accompanies much of what he has to say about Zink. “It was so emphatic, so presumptuous, in a good way,” he says. “There was a feisty tone to it, not quite as strong as ‘You don’t really know anything about birds,’ but something like ‘They call you a New Yorker reporter and you didn’t even write about the Balkans?’ ” He wrote back to thank her, “and the next thing I knew,” he says, “I was getting, like, five emails a day.”

Franzen encouraged her to publish her work, so much that he started to annoy her. “I was, like, either you’re going to support me in practical ways, or you’re going to shut the fuck up about my talent.” Eventually, she sat down and wrote The Wallcreeper, sending parts of it first to Franzen, and then the whole thing to Dorothy, who published it. So, in a way we have Franzen to thank, not for Zink’s work, but for not having to wait any longer for it than we had already.

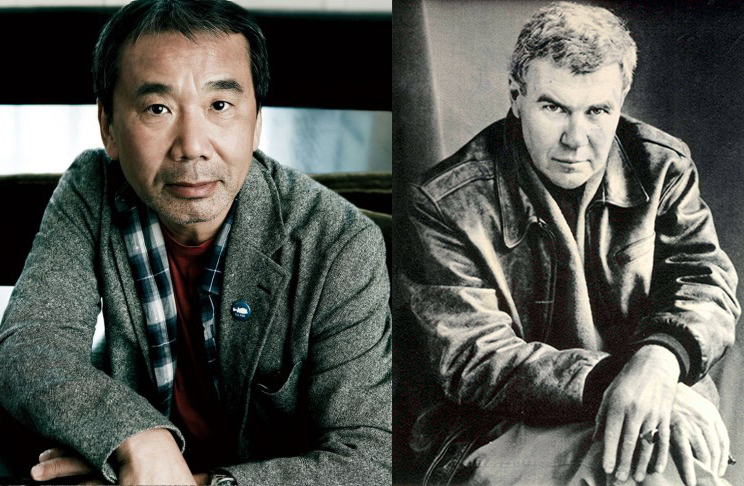

Haruki Murakami + Raymond Carver

Murakami was obsessed with Carver long before the two writers met—according to the Seattle Times, it only took reading two of his stories (“So Much Water So Close to Home” and “Where I’m Calling From”) to convince Murakami that Carver was a genius. Murakami, who had already published a couple of novels, which hadn’t yet been translated into English, began to read and translate all the Carver he could get his hands on. So when Murakami asked Carver for a meeting, the latter agreed. Murakami and his wife came to the United States for the first time, visiting two places: Princeton, because it was the alma mater of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Carver’s home in Washington.

They got along, and afterwards, Carver wrote a poem that he dedicated to Murakami. It begins: “We sipped tea. Politely musing / on possible reasons for the success / of my books in your country. Slipped / into talk of pain and humiliation / you find occurring, and recurring, / in my stories. And that element / of sheer chance. How all this translates / in terms of sales.” Carver also promised to visit Murakami in Japan, and reportedly, Murakami and his wife had a bed specially made to accommodate Carver’s large size—but he never came. He died in 1988.

Somehow, at no point during his visit did Murakami tell Carver that he was a writer too. “I guess I should have done that,” he told the Harvard Crimson in 2005. “But I didn’t know he would die so young.”

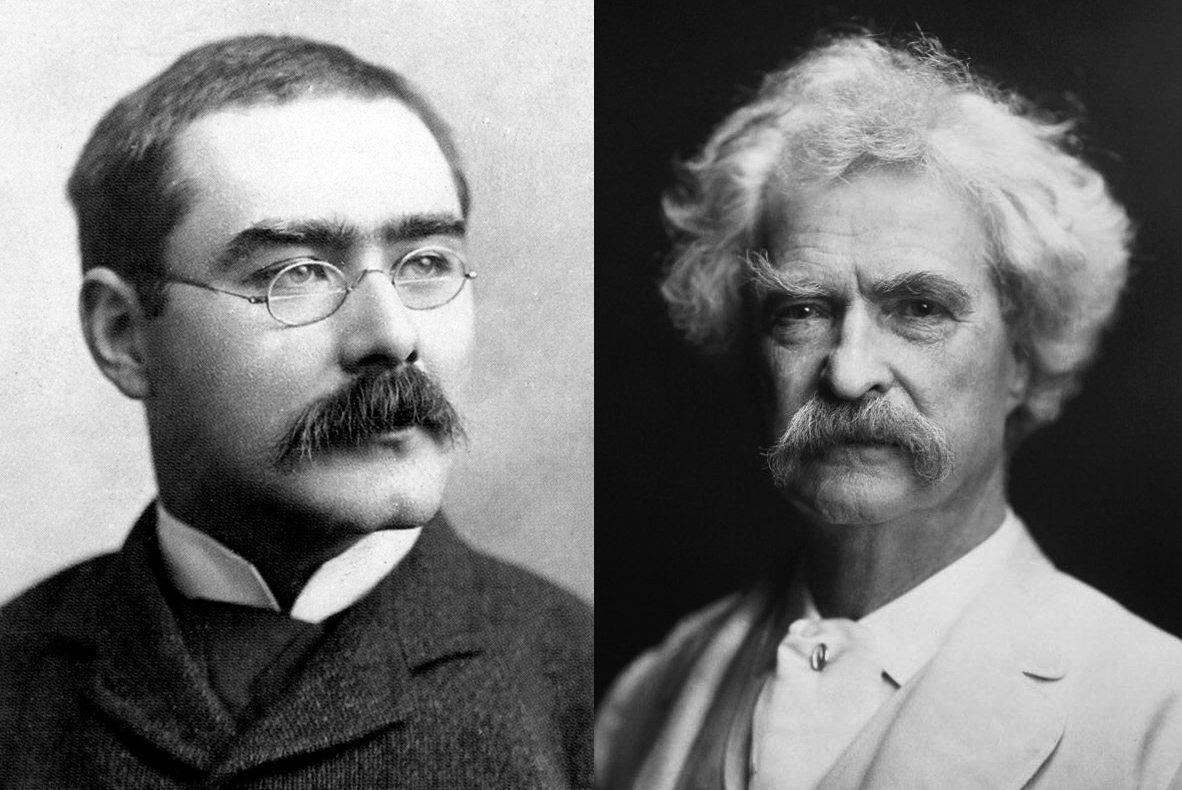

Rudyard Kipling + Mark Twain

In 1889, a 23-year-old Rudyard Kipling decided to track down Mark Twain, who he much admired. After much contradictory advice and rumor-chasing, he made his way to Elmira, where a “friendly policeman” told him that sure, he’d seen Twain—”or some one very like him driving a buggy the day before.” Kipling recounts approaching his prey in his essay on the subject:

Then he was within shouting distance, after all, and the chase had not been in vain. With speed I fled, and the driver, skidding the wheel and swearing audibly, arrived at the bottom of that hill without accidents. It was in the pause that followed between ringing [Twain’s] brother-in-law’s bell and getting an answer that it occurred to me, for the first time, Mark Twain might possibly have other engagements than the entertainment of escaped lunatics from India, be they never so full of admiration. And in another man’s house—anyhow, what had I come to do or say? Suppose the drawing-room should be full of people—suppose a baby were sick, how was I to explain that I only wanted to shake hands with him?

Well, there was no sick baby, and Mark Twain welcomed Kipling in, much to Kipling’s delight. “This was a moment to be remembered,” he wrote, “the landing of a twelve-pound salmon was nothing to it. I had hooked Mark Twain, and he was treating me as though under certain circumstances I might be an equal.” But seventeen years later, after Kipling had become famous, Twain had become one of his biggest fans. Show me a salmon that could do that.

Harper Lee + Truman Capote

What’s meet-cuter than the boy next door? When Harper Lee was six, and still going by Nelle, a boy named Truman moved in next door to her family’s home in Monroeville, Alabama. They were total opposites: she an oft-barefoot tomboy running wild, he a clotheshorse who always had a book in his hand. But they were both unlike anyone else in their town, and they both loved Sherlock Holmes, and so they became fast friends. “Nelle was too rough for the girls, and Truman was scared of the boys, so he just tagged on to her and she was his protector,” said one family friend. The rest is history—catty, competitive history, but history nonetheless.

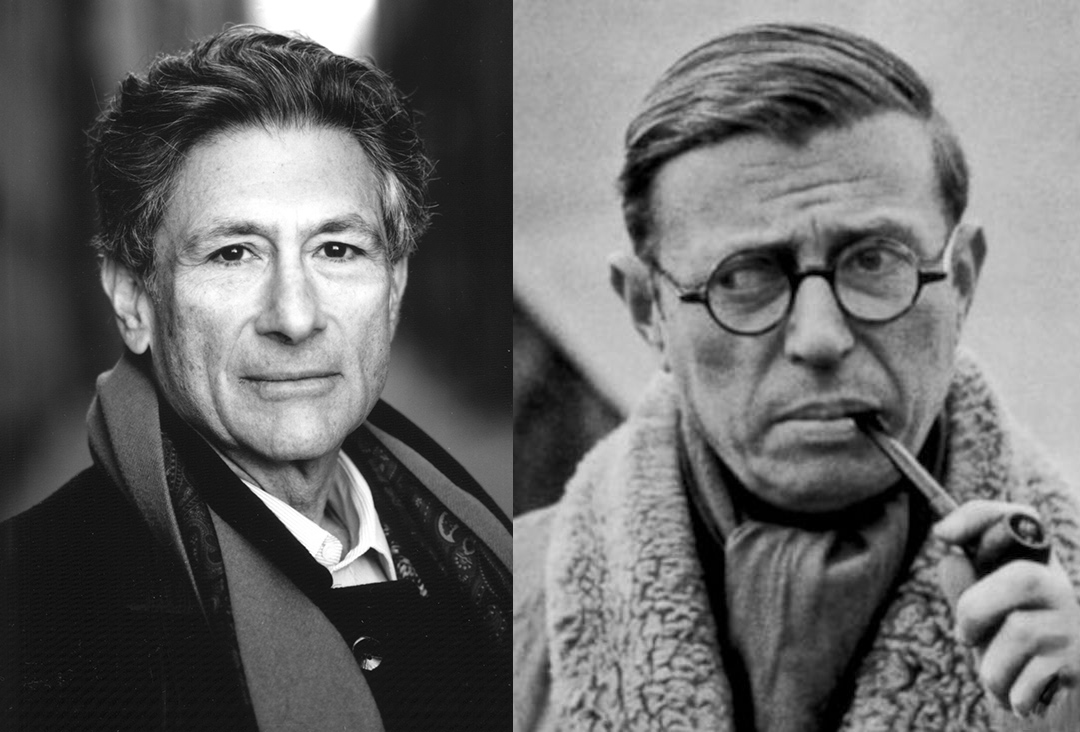

Edward Said + Jean Paul Sartre (+ Simone de Beauvoir + Michel Foucault)

In early 1979, Edward Said received a telegram from Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre, inviting him to “attend a seminar on peace in the Middle East” that March. “At first I thought the cable was a joke of some sort,” Said wrote in the London Review of Books. “It might just as well have been an invitation from Cosima and Richard Wagner to come to Bayreuth, or from T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf to spend an afternoon at the offices of the Dial.” Once he realized that the message was legit, he quickly accepted and readied himself to travel to Paris.

When I arrived, I found a short, mysterious letter from Sartre and Beauvoir waiting for me at the hotel I had booked in the Latin Quarter. ‘For security reasons,’ the message ran, ‘the meetings will be held at the home of Michel Foucault.’ I was duly provided with an address, and at ten the next morning I arrived at Foucault’s apartment to find a number of people—but not Sartre—already milling around. No one was ever to explain the mysterious ‘security reasons’ that had forced a change in venue, though as a result a conspiratorial air hung over our proceedings. Beauvoir was already there in her famous turban, lecturing anyone who would listen about her forthcoming trip to Teheran with Kate Millett, where they were planning to demonstrate against the chador; the whole idea struck me as patronizing and silly, and although I was eager to hear what Beauvoir had to say, I also realized that she was quite vain and quite beyond arguing with at that moment. Besides, she left an hour or so later (just before Sartre’s arrival) and was never seen again.

When Said finally met Sartre, he was no less disappointed. “Sartre’s presence, what there was of it, was strangely passive, unimpressive, affectless,” he wrote. “He said absolutely nothing for hours on end. At lunch he sat across from me, looking disconsolate and remaining totally uncommunicative, egg and mayonnaise streaming haplessly down his face. I tried to make conversation with him, but got nowhere. He may have been deaf, but I’m not sure. In any case, he seemed to me like a haunted version of his earlier self, his proverbial ugliness, his pipe and his nondescript clothing hanging about him like so many props on a deserted stage.” Sartre died a year later.

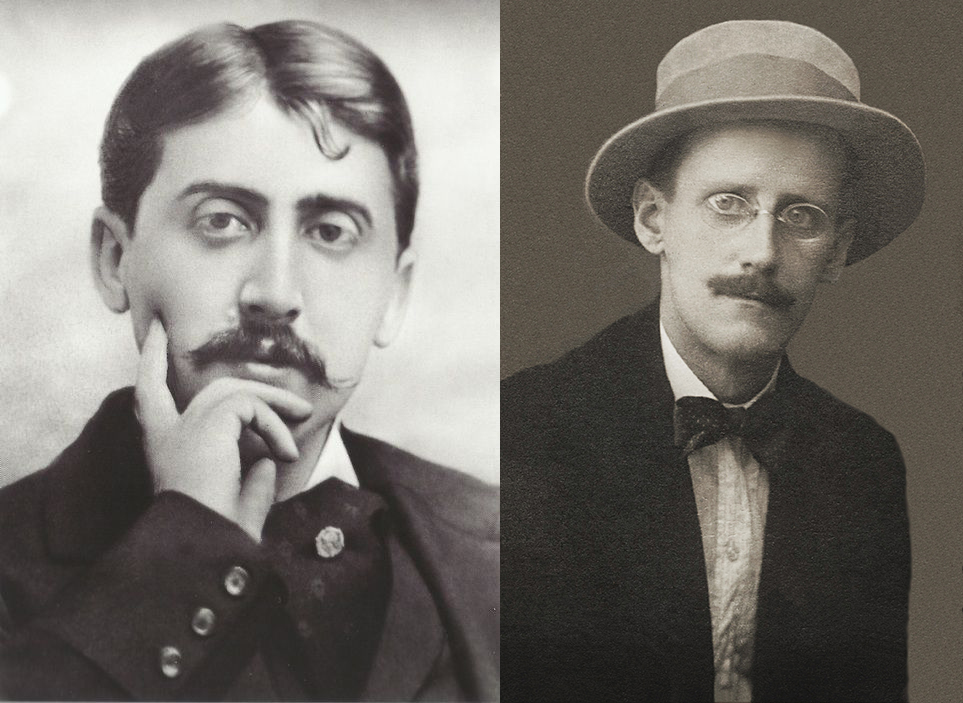

Marcel Proust + James Joyce

Proust and Joyce met when they were set up on a blind date of sorts—a four-way blind date that also included Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky. The party was arranged by British art patrons Sydney and Violet Schiff, who had, according to Craig Brown’s Hello Goodbye Hello, “been plotting to gather the four men they consider[ed] the world’s greatest living artists in the same room.” Proust showed up around 2:30 in the morning, and when Joyce woke up, they were introduced. There are many accounts of what followed, but all of them are bad. Joyce told his friend Frank Budgen that “Our talk consisted solely of the word ‘No.’ Proust asked me if I knew the duc de so-and-so. I said, ‘No.’ Our hostess asked Proust if he had read such and such a piece of Ulysses. Proust said, ‘No.’ And so on. Of course the situation was impossible. Proust’s day was just beginning. Mine was at an end.” But William Carlos Williams and Ford Madox Ford, who were both on hand, agree that the two men did exchange more words than that—if only about their many complaints and illnesses.

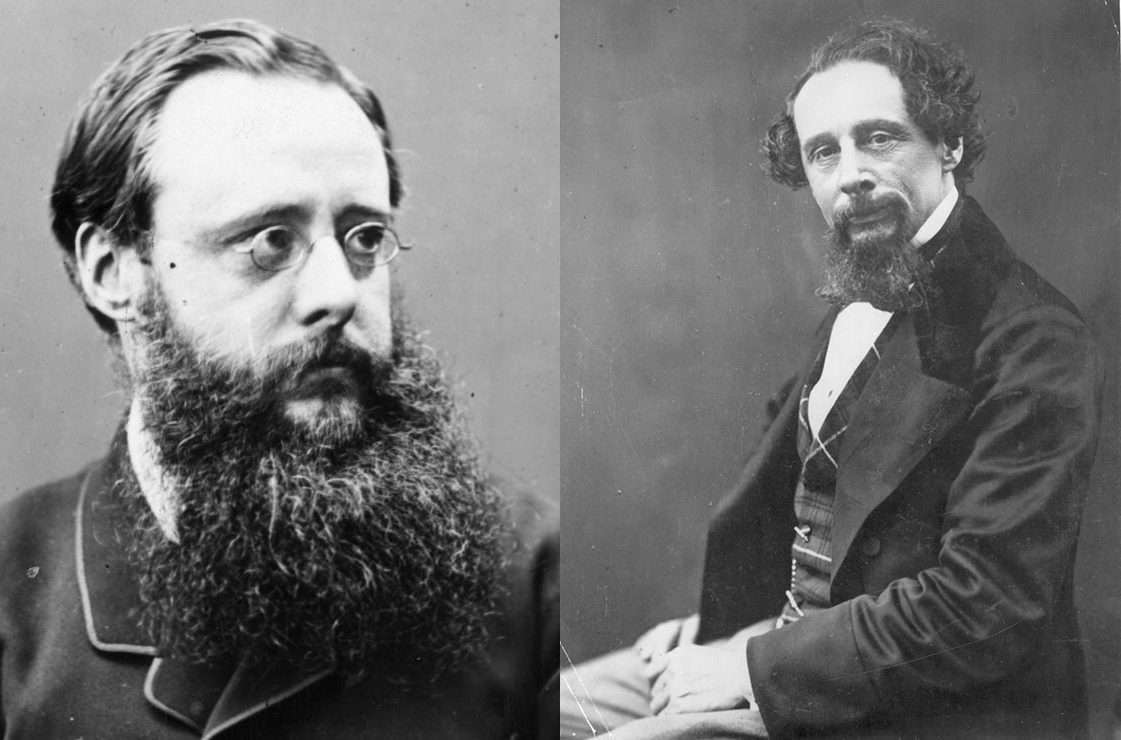

Wilkie Collins + Charles Dickens

Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens met in 1851 when they were introduced by their mutual friend, Augustus Egg. If that isn’t cute enough for you, they were introduced because Egg had recruited the 27-year-old Collins for Dickens’s amateur theatre group. Together, they put on a production of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Not So Bad as We Seem later that year, and became best friends in the process. (Edward Bulwer-Lytton, in case you don’t know, is the fellow who first wrote “it was a dark and stormy night,” as well as “the pen is mightier than the sword.” No one reads him now.)

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.