The Time Giuseppe Verdi Battled *Actual* Censorship

On Italian Radicals Who Fought For Freedom

The issue of defining free speech has arisen each year that I have lived in Italy. For me, it goes straight to my heart. Sometimes it touches an identity pertaining to country, sometimes it centers on denial, on censorship and its array of meanings to an individual.

It is absolutely true, on one level, that Italy is one of the freest countries in the world. There is not a day that goes by in the present crisis, this endless uncovering of deeper and deeper layers of corruption and false arrangements, that I am not struck by how much is discussed, debated, analyzed, and freely joked about. Free speech has a very great intellectual expanse. Yet free speech is often a dance, calculating, unyielding, fixed—a set of sounds and furies that often don’t mean what they say, abstractions very far from facts or life in the present. I could run an analysis of it, as the newspaper analysts do, from every point of view, yet I want to get at something else—a friction in me.

*

Many voices challenging censorship and, thus, expanding free speech in the Parma region have been artists. Their interest in truth is specific and as forceful as trumpet blasts. Giuseppe Verdi experienced artistic, political, and social censorship. Living and working in the decades in which Italy was trying to unify, his music often gave aspirations to a country that hoped but did not yet know if it existed. His librettos never sidestepped the dark contradictions of character and power. The subjects, in their expressiveness, gave independence to feelings that often were literally dangerous.

Verdi’s great choruses embodied collective voices that had no voice—the poor as well as the educated, most of whom suffered under the occupation of foreign rulers. Like Mazzini in politics, in some way Verdi’s artistic vision was liberal: not merely political, but social and requiring great moral strength. In Nabucco and I Lombardi melodies pass from one person, one group, to another, in swells of public consciousness.

Liberty was risky and was also the issue of the day. There were the radicals who wanted Italy to become a country, a republic; the moderates who wanted help from the house of Savoy; and the conservatives who wanted the Papal States to govern. Verdi stood with the Republicans. His censors in the north were the occupying Austrians and the Catholic Church. Their unaesthetic political concerns were a presence throughout most of his life. Verdi’s exasperated resistances required enormous amounts of energy and moral courage, as well as the realism to see when he could not get his way. Putting the idea of liberty and power into characters was always a problem because of repressive control. Even on opening night, the struggle over content might be unsettled and red-hot.

Living and working in the decades in which Italy was trying to unify, Verdi’s music often gave aspirations to a country that hoped but did not yet know if it existed.

Stiffelio, a drama about a Protestant minister and his adulterous wife, which used biblical texts as lyrics, is one kind of example of offense to the community that Verdi’s feeling for liberty embraced. It was unthinkable that Christ’s words for forgiveness could be uttered on a stage. The censors could not allow Protestantism to be portrayed as a religion in which individual conscience mediated guilt.

After the censors worked out their objections, the character of the pastor was stripped of authority and he had to become an ordinary member of a sect. The power emanating from his pulpit is taken away. Since Catholic priests cannot marry (the idea of sex for men of God officially renounced), the person pardoned in the scene is not his wife. The person’s sex is not clear. The drama, and also the universe representing another way of life, is diminished until art cannot make it come alive to an audience. Verdi denounced the opera’s “castration.”

On opening night in Milan, some of the singers wanted to perform the original text. They were under court order not to deviate. Nevertheless, some uncensored librettos mysteriously circulated. The performance had many ups and downs, and in the end the censors were attacked for the “ruin of the score.” The experience is not uncommon in the history of Verdi’s art.

Here is a letter as he starts work on what becomes Rigoletto: “I might have yet another subject, which, if the police were to permit it, would be one of the greatest creations of modern theater. Who knows? They allowed Ernani; maybe they [the police] would permit this too. And here [in my score] there are no conspiracies . . . PS: As soon as you get this letter, get yourself four legs: run all over the city and try to find an influential person who can get the permission for Le Roi s’amuse [Victor Hugo’s work and the basis for the plot]. Don’t go to sleep; get moving; hurry.”

The libretto becomes a long, painful set of struggles and compromises. In his letters, he expressed the sense of frustration and humiliation. “The old man’s curse, so original and sublime in the original, becomes ridiculous here, because the motive that drives him to utter the curse no longer has its original importance, and because he is no longer a subject who speaks so boldly to the King. Without this curse, what purpose, what meaning, has the drama? The Duke becomes a useless character and the Duke absolutely must be a libertine … without that, this drama is impossible.” “What difference does the sack make to the police? Are they afraid of the effect it has? But I allow myself to say: Why do they think they know more about this than I do? Who is the Maestro? Who can say this will be effective and that will not be?”

In Nabucco and I Lombardi melodies pass from one person, one group, to another, in swells of public consciousness.

Perhaps even more difficult than the struggle for artistic liberty and truth, but certainly consistent with his personality, was his resistance to social pressure in his private affairs. In the village of Sant’ Agata, too, Verdi expressed himself and violated what were very common assumptions. Living with Giuseppina Strepponi, once a brilliant soprano and the mother of several illegitimate children, he offended nearly everyone. (His first wife and their two children had all tragically died of illness within four years of his marriage.) Strepponi and he did not marry until Verdi was 46.

But when Verdi filed a lawsuit against his own parents, asserting that “Carlo Verdi has to be one thing, Giuseppe Verdi something else,” he was perhaps creating an even more offensive breach. Verdi broke with his parents. He dissolved their financial interdependency, and even officially protested their use of a chicken coop, the rights to which he took away from his mother. He evicted his parents from a house they had helped pay for. He didn’t respond to their growing debts, and eventually he legally separated from them altogether. His behavior cost him the approval of the community.

In the final contract with his father, you see his harshness and exasperation. You feel in those final conditions, when he pays back his debts and offers them a small house and stipend, that he has gone to great lengths to publicly violate a code. He doesn’t want to conform and be forced to live in the community according to their rules of common decency. He insists, unambiguously, on disturbing the common illusions and customs, while making it clear where he stands. Dutiful morality will not bind him, and he chafes at people’s determination to judge. His behavior is monstrous.

Arturo Toscanini, whose birthplace, a small, narrow, dark, wooden-beamed stone structure, is on the western side of the torrente Parma, is another giant, godlike figure who in his artistic positions also resisted and took up issues of censorship. The badly typed transcripts of his tapped telephone conversations, once he begins to resist Fascism, mark the beginning of Toscanini’s exile. His emotional letter explaining to Wagner’s daughter, who is fascinated by Hitler, how he will not serve as the director at Bayreuth, is extremely sad but explicit: what he thought was a “temple” is an “all-too-common theatre.” He gives up his chance to be the director at Salzburg as Hitler’s power grows. He telegrams Bruno Waiter: “It’s useless for me to wait for your letter My decision is final however painful stop I have only one way to think and act I hate compromises I walk and shall always walk on the straight path that I traced in life.”

His fire finds him accepting an invitation to direct the orchestra in Palestine in 1937, as if to raise a sound: we must open our hearts. His uncensored voice is the one that can often be heard shouting over the whole of the NBC Orchestra in recordings made in the 1950s in America. It erupts, driving the music and commanding the musicians to give more. In the small museum in the house in Parma where he was born, there is a documentary made by an American. It is possible to watch Toscanini frolicking and turning somersaults with his grandchildren and to see his arms conducting in a sequence that reveals that he directs music by making figure eights, circular movements that neither begin nor end, but move like giant signs for infinity. His energy beats in lifted, sharpened rhythm.

Giovanni Guareschi, whose script for the movie version of Don Camillo was written in the San Francesco jail in Parma, smuggled it out between the pages of two books. His imprisonment is another story of censorship and the community. He was imprisoned because he published a letter in Candido, a political magazine that was allegedly written by Alcide De Gasperi before he became the first Prime Minister of Italy. In the questionable letter, De Gasperi asks the Allies to bomb Rome. The courts found the letter to be false and charged Guareschi with inventing it. We may never know the whole story of the letter or what Guareschi hoped to achieve. But he served his sentence. It seems that Guareschi, who in a very conservative way was a champion of individual freedom, thought De Gasperi was a man who should not be looking to foreign countries for Italy’s political stability and solutions. Whether the letter was true or false, Guareschi was asserting a kind of political patriotism in his protest.

The books in question, Vita di Benvenuto Cellini and La Poesia di Giuseppe Giusti, resting on a shelf in the Guareschi family library in Roncole, contained the smuggled movie script on typewritten pages, folded in quarters, until recently. His children noticed that the books were out of place. When they took them down from the shelf, the script fell out. They realized that their father had written it under the noses of complicit censors and smuggled his work out in the books. The go-between, who remained anonymous, had simply slipped the script and “their protective covers” back on the shelves. The script was written in violation of the rules of the prison.

These Parma voices stand as examples of how censorship has had meaning in artists’ lives and how it has not had only one political coloring even in recent history. Resistance comes in all colors. The individual in Italy has nearly always had to accommodate the effects of politics. Italy’s history contains an unending tale of courageous, resourceful, and active anticonformists who have worked around and through politics while carrying forward social and moral concerns. I am left now with how to make the shift into a personal story about a different definition of censorship not seem irrelevant and trivial. Myriads of disapproving Italian intellectuals are murmuring “impossible.” I vaguely see them, like paintings in the Middle Ages, within crowded celestial rings, people who are never freely alone.

__________________________________

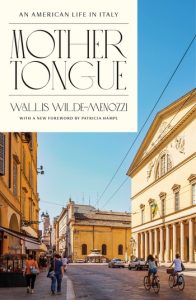

Excerpted from Mother Tongue: An American Life in Italy by Wallis Wilde-Menozzi. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, North Point Press, an imprint of FSG.

Wallis Wilde-Menozzi

Wallis Wilde-Menozzi's books include The Other Side of the Tiber and Toscanelli's Ray. Her poetry, essays, and translations have appeared in Granta, The Best Spiritual Writing, Words Without Borders, and Tel Aviv Review. A collection of her essays was published in Italian as L'Oceano e'dentro di noi. Currently she is teaching migrant women who are waiting for their Italian papers.