The Thrill of Discovery: How Hidden Messages Make Fiction Fun

J. Nicole Jones on the Writers Who Create Literary Puzzles and the Readers Who Solve Them

In March of 2020, I picked up Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees. The paperback had been sitting unread on a shelf in my living room for years. Nearing the final pages, when the protagonist travels overland by tree branch, a stranger appeared unexpectedly in the text. “Je suis le Prince Andrei,” says this man, and I felt the same swell of elation as when encountering a friend by chance walking down the street or in a subway car: that comfort of belonging to the connected world, of seeing and being seen by people with whom you’ve shared time and space and memories.

Improbably, here was Prince Andrei Bolkonsky from War and Peace in a Calvino novel; the world had been locked down for several weeks by then to try and slow the spread of Covid-19, and the overwhelming excitement I felt at meeting someone I recognized, even a fictional character, took me by surprise.

As a reader, those secrets light the narrative with an aura of excitement.When you find an Easter egg—a hidden reference to other dimensions or worlds—within a game, a song, or a book, it feels like sharing a secret with the creator. It’s exciting. It’s like a wink from someone with whom you share a special connection—or with whom you’d like to. Taylor Swift and her fans undoubtedly have a symbiotic relationship, but the illusion of personal connection is probably weighted more heavily on the fans (or the players, or the readers).

But what’s the difference between one of these Easter eggs and a plain old allusion or reference? Each is a nod to sharing esoteric or specific knowledge, leading the like-minded to the same joyful destination. There’s nothing to forge closeness, for better or worse, like a secret, and the resulting feeling of connection may ease the loneliness that comes with rewarding and fun, but often solitary activities.

In Calvino’s novel, Prince Andrei promenades the little baron’s orange grove openly. Perhaps Easter eggs, contrasted with allusions, are more clue-oriented to figuring something out. Last September, Google created a game oriented around Easter eggs where fans pulling up its search bar could solve as many as 33 million puzzles collectively to open an animated vault revealing upcoming Taylor from-the-vault tracks. But can’t what’s hidden in the text, what the clues are pointing to, be meaning in a work as well? Even if that can be more subjective and less tangible than song titles, or a room filled with bananas.

Literature has always been full of allusions. To the Classics. To religious and historical texts. There’s the famous Nabokov story, his spookiest story (sigh… all roads lead to Montreux?), “The Vane Sisters.” The narrator’s friend, and the sister of a student who has committed suicide over the end of a love affair, has an interest in the occult and is convinced that messages from the dead may be hidden in puzzles all around. Of course, within the text, there is a puzzle that I won’t ruin, but the solved puzzle does contain the meaning of the story, at least in part. Additionally, the name of the sister who dies is a reference to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. In this story, then, we have both allusion and Easter eggs.

Nabokov is the king of clues. Pale Fire and Lolita, each jumping over spooky and delving into outright horror, are full of allusions and references for readers: to Edgar Allan Poe, to a real-life kidnapping, to his own works (see Hurricane Lolita in Pale Fire). But these seem to be as much for him as for the reader. Even if you don’t get every one (I am certain I do not), you can feel the pleasure in the writing of it. The sparks of connections being made. As an author, those can be what keep you going, when you are only writing for yourself, and as a reader, those secrets light the narrative with an aura of excitement. We can feel the creator’s connection to what they’re making. We can feel it’s important to them. That they’re having fun with it, and we can too.

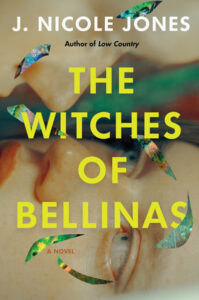

At least, after writing my first novel, I think that must be the case. The Witches of Bellinas is about a woman who feels alone in an isolated town in coastal California. Her marriage is falling apart, she suspects the townspeople of sinister acts, but she isn’t sure exactly what those are yet, and she feels herself losing touch with who she used to be. Also, there is maybe some magic influencing the town.

Easter eggs, what small ones I managed, and allusions are out there to be discovered or to remain hidden.Writing can feel like such a solitary act over a lengthy period of time. I first started this book in 2017, after I had spent a summer living in a windswept house in a small, eerie town miles and miles from anywhere but the Pacific Ocean and beautiful redwood forests. How could I feel so detached in such a beautiful place, I wondered? But then I started to write the first of many drafts that would become this book. Infusing it with connections to other works that were meaningful for me, that made me smile, made a solitary act feel less lonely.

I was writing for myself, but for those hours when I could be at my desk, I was among characters who felt like friends imagined by other authors. Literary allusions for the author aren’t necessary for the reader’s understanding, but they may turn into moments of delight discovered by those who happen upon recognition. In that way, they are again more Easter egg than reference. There for the fun of the moment, but also as a direction from your writing brain: Why do I keep thinking of the cat in Lolly Willows? Why have I chosen someone’s name as this or that? They can be a bridge to meaning for the author while writing, to puzzling out what’s not yet on the page.

The main character in The Witches of Bellinas is named Tansy, and I couldn’t tell you where that name came from, but at some point, I realized it was a nickname for Constance, and with joy, what felt like finding an important clue for me alone, I made her full name Constance Black, after Constance Blackwood, Shirley Jackson’s character from We Have Always Lived in the Castle. (While her sister Merricat is probably my favorite character from literature, in life, I am the consummate the elder sister, more the protective, mild Constance.)

My Constance, aka Tansy, becomes obsessed with a book she finds, which is a sister book to a fictional one in Hrabal’s Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age: Anna Nováková’s Book of Dreams. There are a couple of Barbara Comyns references, a prominent Rosemary’s Baby reference, and a nod to Donald Antrim’s Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World. All of these felt like puzzle pieces for myself while writing: a part of me saying, “Keep going. You can create something where all the things you love live in the same place even in a tiny way.”

I can’t speak for all authors, of course. This is just one of the little things that helped me when I felt very alone, immersed in a narrative centered around loneliness. Should I have left these references on my drafting notes, just for me to remember? Well, it is too late now. I can’t help but share about the things that I love. These books and characters have brought joy to my life, far beyond just my writing life. Creating may feel like a solitary act, but I have been lucky enough to find a home for my novel. Having my book out in the world means that it is no longer just mine. Easter eggs, what small ones I managed, and allusions are out there to be discovered or to remain hidden. Secrets offer their own kind of power, as Tansy herself has to find out.

__________________________________

The Witches of Bellinas by J. Nicole Jones is available from Catapult Books.