Long ago. Saying those words puts me in a strange mood. Long ago – what does that mean? I’m not all that young, but I’m not that old either.

Long ago. From where I stand now, that could point to a time only a few years back, or to when I was born forty-odd years ago, or to much earlier than that. Yes.

Long ago, there was a time when I fell in love. With a certain man.

I thought of him as my big brother at first, from the time we met to when the love part began. Apparently, I called him uncle at the beginning – how many times, I wonder? I hadn’t yet turned two, you see.

‘Stop calling me uncle,’ I’m told he said as he swept me up in his arms. At that age, I didn’t know enough to wipe my own mouth, so I slobbered all over his chest as I snuggled in his arms, ignoring his request and chirping ‘Un-ku! Un-ku!’ over and over. ‘I’m only in junior high – how can I be an uncle?’ he’d teased, giving me a big squeeze. Don’t say uncle, my mother laughed, say big brother. Naa-chan is good too. Naa-chan. Naruya Harada.

His name.

*

‘You loved him all along, didn’t you?’ my mother remarks every so often. ‘From the very beginning.’ It still surprises her.

She’s right, though. Even in grade school, I was sure I loved Naa-chan.

You may wonder what a child that young can know of love. And you’d be right to wonder.

I myself had no idea why I loved him so. I only knew that for some reason I felt warm all over when he came near. A languid, enfolding warmth. I had no way to express that love, however, so I just tagged after him whenever I could, calling out ‘Brother’ this and ‘Brother’ that. I was really small then, a helpless, unformed child too young even for preschool.

I must have been four when I started kindergarten. Until then, I had spent all my time with my parents in our very happy home, so kindergarten was a huge adjustment, let me tell you. For a start, I hated my classroom. Why did other kids my age have to run around like that? Why did the organ make such a clackety-clack when the teacher played it? Why did we children have to sing all those silly songs?

The upshot was that I chose to keep my distance from the other children as much as possible, squatting in the furthest corner of the schoolyard with my eyes fixed on the ground. Ground that was teeming with plant and insect life. The green leaves radiating from the base of each dandelion. The shepherd’s purse that rustled if you shook it the right way. (My mother had just taught me how.) A cluster of pointed leaves that would prick my arms if I touched them. Light-green grass with tiny buds sprouting in between the stalks. Scurrying ants, so tiny that the grass must have felt like a jungle to them. Little grasshoppers that soared to amazing heights given their size. Grass moths that darted sideways through the air. Other insects, like the tiny grey butterflies and the pale cloudy-yellow ones who danced above my head, as well as the lethe butterflies – the ones that flattened their wings upon the soil.

Squatting there with my eyes trained on the ground, I discovered that I was able to enter into that little world, to become one with those plants and insects for extended periods of time. In that world, there were no mean kids to yank my hair or push me and the other children around. Instead, I’d found a spot where every plant and insect devoted all its energy to just trying to survive.

The time I spent with Naa-chan put me in that same frame of mind. It was warm and familiar, a bright, quiet place where I could feel calm and secure. Yet at the same time it was very lonely.

*

At last, the day came when I could leave that nasty kindergarten behind and move on to elementary school. I had no choice in either case, but the elementary school was certainly better than kindergarten. In school, it was only during recess that the kids could run wild and harass their classmates.

The school had a reading room, but I searched everywhere in the building to find a quieter spot. I climbed the stairs to the second floor and peeked into the classrooms, where the bigger boys and girls gawked at me, followed the corridor to take a look at the science room, where the life-size human skeleton on display glared back, climbed to the top of the staircase to find the door there shut tight, no matter how I pushed and pulled, and then back down the stairs to the basement, where the janitor’s room was located.

‘Well, well, what have we here?’ the janitor said. ‘You’re a pretty small kid to come all the way down here!’ He was a big man. I had to lift my chin to look at him, as if I were looking at the ceiling. He was beaming. ‘Call me Takaoka,’ he said. ‘I’ve been working here for some time. A janitor’s work is pretty interesting, did you know?’

I was a little surprised. None of my teachers had talked to me this way before.

‘What class do you teach, Mr Takaoka?’ I asked. Mr Takaoka laughed.

‘I’m not a teacher,’ he said. ‘I take care of the school.’ Take care of the school? Now I was even more confused.

‘The teachers take care of you guys, right? Well, someone has to take care of your classrooms, and the schoolyard too.’

My gaze was fixed on Mr Takaoka. I liked him right away. He was looking me straight in the eye. For some reason, he seemed to have taken to me as well.

‘Come down and visit sometimes. Not too often, though. I have to look after the school, remember.’

Happy to have found at least one place in the school to call my own, I climbed the stairs back to my classroom.

*

There were other quiet places too.

The science room with its resident skeleton was scary, but it didn’t take long to get used to. Most of the kids who used the reading room were older, so it was daunting at first to go in there, but I soon discovered an out-of-the-way desk where I could sit without being bothered. Outside the building there was the far corner of the schoolyard’s flower bed. A shady, secluded spot in the outdoor corridor that led to the gym. A hidden nook beside the school entrance. Surprisingly, the nurse’s room wasn’t an option. Some children clustered there to jabber and run madly about, while others just wanted attention and knew how to get it. At any rate, that’s what the nurse’s room was like in my school.

Sometimes the school nurse would accost me in the halls.

‘You’re too pale,’ she admonished me. ‘And your hair’s too long. Wouldn’t you feel better if it were trimmed?’

My hair had never been cut. At first it was my mother who liked it long, but soon I was the one who resisted anyone touching it. By the time I was at elementary school it was down to my waist, and Naa-chan treasured it as well.

‘Your hair is so soft and silky, Riko,’ he would say, stroking it. I would quiver with happiness. A lid within me had somehow been opened, allowing my emotions to flow. How could I let anyone cut the hair I was growing for him to run his fingers through? It was clear to me that the school nurse hadn’t a clue how deep someone’s feelings could be, so deep they could make her shake inside.

‘You fainted during morning assembly, didn’t you?’ the nurse continued, fixing me with a stern look. ‘Are you eating a proper breakfast?’

Of course I was. My mother’s breakfasts were delicious. Fluffy white rice. Fragrant miso soup, made with a broth of dried sardines. A sweet yellow omelette. Sliced pickles. Dried seaweed. Boiled spinach with a touch of soy sauce. All topped off with a cup of roasted green tea. By the time I finished, I was practically ready to go back to bed.

No, it was the school lunch I couldn’t stand. It wasn’t the taste so much as the weirdly lightweight and slightly yellowed plastic dishes the lunch was served on. One look at those dishes and my appetite vanished. Eating with a group of children bothered me too, as did being served by whoever’s turn it was that day. I shuddered to see how they slopped food into my bowl – I just wanted to be left alone to serve myself, so I was more than happy when my turn came round.

My mother said that when she was a schoolgirl, students couldn’t leave the room until they had finished their lunch.

‘It wasn’t that bad in my elementary school,’ Naa-chan said. ‘Come to think of it, though, the stricter teachers in the other classes would keep an eye on things until lunch period was over.’ As far as I was concerned, all mealtimes should be special. It didn’t matter how good the food tasted when we were forced to eat like that – I hated it.

‘Aren’t you a little stuck-up?’ Naa-chan said, smiling.

‘It’s not that. I just like things to be pretty.’

Years later, my mother laughed at this attitude of mine. My, but you were a fussy little girl, she said. But I was dead serious.

*

Let me talk a little more about Mr Takaoka. Why? Because our peculiar bond had such an impact on my future.

The other children didn’t like Mr Takaoka very much. Perhaps they found his appearance scary. He was a big man with a massive head and a face that made one think of a demon, despite his always cheerful expression. He had a deeply furrowed brow, unusually thick eyebrows, flashing eyes and full lips. He did have a fine aquiline nose, though – indeed, had his features been better aligned, he would have looked exactly like the beautiful Indian prince in my old book of fairy tales. Sadly, that was not the case.

To me at the time, Mr Takaoka was the epitome of age and maturity, but in fact he was only in his late twenties when I started school. I found out later that his father had passed away while he was still in junior high, leaving the family impoverished. Lacking the resources to continue on to university, Mr Takaoka went out to look for work as soon as he graduated from high school, but nothing suitable was available, so for whatever reason he decided to become a Buddhist monk, moving to Mt Kōya to undertake the rigorous spiritual training the temple complex is famous for.

*

When he came to work as a janitor at our school, Mr Takaoka had completed the first stages of that training and had worked as an acolyte in one of the many small temples that dot the mountain. Yet the prospect of life as a monk hadn’t appealed to him – he longed to breathe the air of the profane world below, so he came down from the mountain, followed up on one of his connections and secured the janitor’s job. Perhaps what people saw as demonic about him was the result of the severe austerities he had undergone on Mt Kōya.

The fact that my fellow students shunned Mr Takaoka made me draw all the closer to him.

*

I was in the third grade when I first told Mr Takaoka about Naa-chan.

‘Hmm, sounds like you’re in love,’ was his response. I knew that I liked Naa-chan, but that was the first time I had thought of my feelings as ‘love’. Once Mr Takaoka had suggested it, though, it became clear to me. I was indeed in love with Naa-chan.

Naa-chan would often show up at our home without warning. He seldom told us in advance. When my mother opened the front door and saw him standing there, she would knit her brow and say: ‘You again? You might have let us know.’ Despite her frown, though, I could tell from the way she sparkled how glad she was to see him.

It was right around the time that Mr Takaoka introduced love into the equation that Naa-chan, by then in high school, began to exert a powerful attraction on all sorts of women. When he was nearby, they grew flirtatious: their attitude became more light-hearted, their speech more lilting, their movements more supple, and they unconsciously leaned in his direction.

Naa-chan was a beautiful young man, no doubt about it.

*

Nevertheless, that alone wasn’t what made him so special. There were other things. The curve of his shoulders when he looked down. The line of his jaw when he suddenly lifted up his face. His tranquil manner when talking quietly; his passion when he grew excited. Sometimes he would be flitting about, while at other times he was so still as to make you forget he was there. He was good-looking enough in his animated moods, but even more striking when he just sat there peacefully.

On top of all that, he was a great listener. You knew that you could unburden yourself to him, expose your most deeply held secrets, and he would hear you out to the end. He made all women feel that way. And not just women, either: a certain type of man, too, found him strangely seductive. My father, for example, was drawn to Naa-chan. He loved him like he might a much younger brother.

Naa-chan called my father sempai or senior, as one would call someone above them in school. How that made my father smile! In fact, it was to see my father that Naa-chan began visiting my home in the first place. That’s right. When I was two, Naa-chan had just entered junor high, thereby becoming my father’s kohai, or junior. Not only did they attend the same private school and, later, the university affiliated with it, they were both members of the same soccer club.

‘Did you ever go see them play?’ I once asked my mother. She gave me a funny look, as if the idea had never occurred to her. My mother was a real homebody. She claimed that crowds made her dizzy, and that she didn’t like socializing with other wives. These were the excuses she came up with, but really she just enjoyed spending her time quietly at home, keeping her relations with our neighbours to a bare minimum. I sometimes think that her dislike of other adults was similar to the dislike I felt for the other children at school. She reserved her smiles for my father, and for Naa-chan.

*

‘You should take up a sport, Riko, or maybe take lessons of some kind,’ Naa-chan said when I entered elementary school. Thanks to his suggestion, I threw myself into studying the koto. My kindergarten classmates tended to gravitate towards calligraphy, swimming, ballet and English conversation classes, but I would rather be caught dead than do anything that involved ‘learning together’. My koto teacher, Michiko-sensei, always wore Japanese clothes. She arranged her hair in a small chignon that shone in the light, and she was very much at home in her kimono, which she put on by herself.

‘For a modern girl,’ she said to me after we’d had a few lessons, ‘there’s something about you that smacks of the old days. Your long hair really suits you. It’s very beautiful. If you ever cut it off, let me have it, all right?’

That was the sort of thing only Michiko-sensei could come out with. I hated the idea of parting with my hair, but if I was ever in a fix and needed to do that, strangely, I felt that she would be the one I’d like to have it.

I loved studying the koto with her. I took practising at home seriously too. Sometimes, Naa-chan would ask me to play for him and I always leaped at the chance. He would lie back on the sofa, close his eyes and listen to me playing. I was so proud in those moments.

Let me talk a little more about Mr Takaoka.

When I was in fifth grade, the school made the decision that a full-time janitor was no longer needed, and Mr Takaoka had to go.

__________________________________

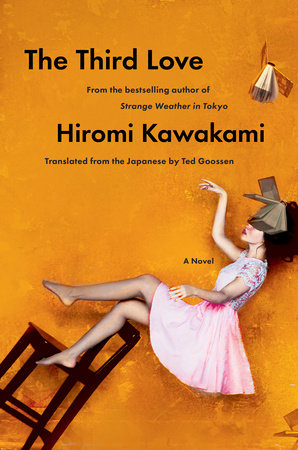

From The Third Love by Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Ted Goossen. Used with permission of the publisher, Soft Skull Press. Copyright © 2025 by Hiromi Kawakami. Translation copyright © 2025 by Ted Goossen.