“The Thing We Know How to Do for One Another.” Seven Poetry Books to Read This February

Christopher Spaide Recommends Andrew E. Colarusso, Kelly Hoffer, Nicole Lachat, and More

“What are we doing? . . . No, I mean—what does poetry do?” That’s D__ speaking. He’s a poet, though you might not know it from the title of the novel he’s narrating: The Copywriter, out this month, by the poet (and now novelist) Daniel Poppick. For “D__,” you could read “Dan”—the author and his protagonist have plenty in common—or you could swap in any number of other accurate d-words: D__ is a dreamer, a diarist, a dawdler, a dope, and (only on rare, rueful occasions) a dick. But the blanks in D__’s name, like everything else in Poppick’s portrait of a poet as an aging millennial man, are deliberate. At his copywriting job, D__ feels as insubstantial as an email sign-off; he identifies as a poet, but the poems dry up for seasons at a time. As we find by reading over his shoulder, he finds his life is best narrated in scattershot notebooks, accumulations of wisecracks, quotations, stoned musings, and parables whose lessons are unclear or (more likely) nonexistent.

Back to D__’s questions. He’s in the middle seat of a row of poets on a cross-country flight. To his right, his friend Will is asleep in the aisle seat; to his left is his ex Lucy, watching tv. “In the window behind her, disparate patches of a large cloud flicker with submerged lightning”; until D__ taps her arm, Lucy is “gasping with laughter over a film about two British men who exchange impressions of celebrities over thousand-dollar lunches”: natural sublimity and art at its most delightfully contrived, respectively. (The film is called The Trip; I recommend it.) “It doesn’t bother you,” D__ asks Lucy, “that the country is about two seconds away from becoming a full-blown fascist death cult and we’ve organized our lives around writing poems for one another that almost no one else will ever read?” Lucy, shaking her head, replies: “Poetry is the thing we know how to do for one another. Spending your time writing it doesn’t make you bad—or good, for that matter.”

The Copywriter is set in the late 2010s, but I’d be hard-pressed to imagine a book that speaks more to what it feels like to read and write poetry in 2026. Even in the page-long scene I’ve just narrated for you, I hear futility and necessity, poetry’s niche appeal and its open-ended generosity. Reading D__’s panicky, prescient words and Lucy’s stirring yet persuasive reply, I think immediately of Renée Good, a wife, a mother of three, and an award-winning poet who is one of several people already killed by ICE agents this year. And when I look over the poetry books that, arbitrarily yet consequentially, happened to be published in this year’s early, terrible weeks, I see neither attempts to solve all our social and political problems (what would that art even look like?) nor distractions from the present (who would want that?). No, I see efforts to do something for one another—where “one another” is an unlimited category, open to anyone with the time and means to listen in.

*

Jeannette L. Clariond, Even Time Bleeds: Selected Poems, translated from the Spanish by Forrest Gander (Princeton University Press)

Some painters specialize in murals, others in miniatures. Some chefs dedicate themselves to tasting menus of one-bite intricacies, with every microgreen tweezered into place and every sauce drizzled just so; others master the art of deep-frying turkeys. (I’m guessing.) To read Jeannette L. Clariond’s Even Time Bleeds—a bilingual selection from across the Lebanese Mexican writer’s career, pairing Spanish originals with Forrest Gander’s lucid translations—is to meet a poet who has perfected poems at every scale, from symphonic sequences and diaristic notebooks to the scoopfuls of one-line poems of her 2003 collection Ammonites.

Some of those short poems may remind Anglophone readers of familiar forms of wisdom literature, koans, or animal fables abbreviated to pocket size: “Agitation is the bee’s tranquility.” Others strike on sonorities and palettes rarely found in American poetry: “Impatience, that wet log.” Not all of Clariond’s effects are reproducible outside of Spanish, in which she can make a melancholy mantra out of the soundalikes “mi ser” and “miseria” (“my being” and “pain”), or grate words together in what Gander calls her “signature gnomic syntax.” But in both its languages, the primary impression left by Even Time Bleeds is one of supersaturated surplus, of a poet who can reinvigorate genres as timeworn as the landscape poem, the creation myth, the family elegy: “For brief moments, I lived, for brief moments / everything went purple: the woman who was gone, / the fatigue, the poplar leaves.”

Andrew E. Colarusso, Pettyg-d (Flood Editions)

How, in 2026, can a poet make something new out of New York City, the most traversed and versified geography in North American literature? Andrew E. Colarusso has a few answers in his second book, Pettyg-d. In “Ditmas Park,” a poem as short as a smoke break but dense with decades of personal and social history, Colarusso talks himself through the neighborhood where he was born and raised, “this place / you grew up crying inside of.” It’s like one of Frank O’Hara’s “I do that, I do that” poems about cosmopolitan Manhattanite living, only for Colarusso it’s 2 a.m, “the Halal spot / just closed,” and all he has to break the quiet are “strings of families and ghosts / coming and gone from this zone.”

His love poems know that no city’s more camera-ready for romance, so long as you acknowledge that giddiness is next to griminess: “Something about this girl / whose laugh is like three mice / playing poker behind a bodega / makes me want to sing all the time,” he crows at the top of “T. Rex.” (He subtitles that one “ft. Marc Bolan,” the glam-rock mastermind; other poems feature Hortense Spillers, Megan Thee Stallion, and Covid-19.)

Again and again, what gives structure to Colarusso’s many-tongued collection—which includes poems in Spanish and in French, reverent elegies and cartoonish dreams, not to mention the filthiest sex poems I bet I’ll read all year—is prayer, the postures and registers of a poet speaking up or down to that titular “pettyg-d.” Or else it’s something like prayer, addressed horizontally, to those dearest to us: “not to faint or fail / against muzzle flash or flames / to this I promise the promise / of you.”

Jake Fournier, Punishment Bag (University of New Mexico Press)

There are some poetry collections you start reading and, only a few poems in, get a read on: instead of bringing surprise or novelty, each new page circles around to the same old themes, to increasingly predictable trains of thought, to tricks that land like tics. Then there’s Jake Fournier’s Punishment Bag, a debut collection so stylistically various, so deviously sequenced, that not once could I guess what species of poem would come next. The book begins with “Natural Piety,” a meditation at one’s desk, pondering rainbows, covenants, and the invisible with a methodical whimsy that recalls the early Elizabeth Bishop. The very next poem? “Quick Recovery,” a persona poem imagining, beat by beat, the hard yet everyday work of an EMT wading into “the sulfurous waters where / they say the boy drowned.” (In the book’s outstanding notes, Fournier explains that he became an EMT not long after writing “Quick Recovery,” surprising even himself.)

There are two title poems, the first one only nine lines, the other seven whole pages. In the first, communication seems just shy of impossible, an arrhythmia of words and images, English and French, double negatives and oxymorons. The second, shedding retrospective light, recounts Fournier’s stint teaching immersive English classes outside of Paris, and his success with the “punishment bag”: less the torture device it sounds like than a Wittgensteinian language game, it’s a black plastic bag full of “texturally and contextually distinct objects” that his troublemaking students would have to touch and describe, in English, to their fellow classmates. What image could be more apt for Fournier’s collection, which cloaks the everyday inside defamiliarizing forms, discovering in the severest subjects a counterintuitive reservoir of play?

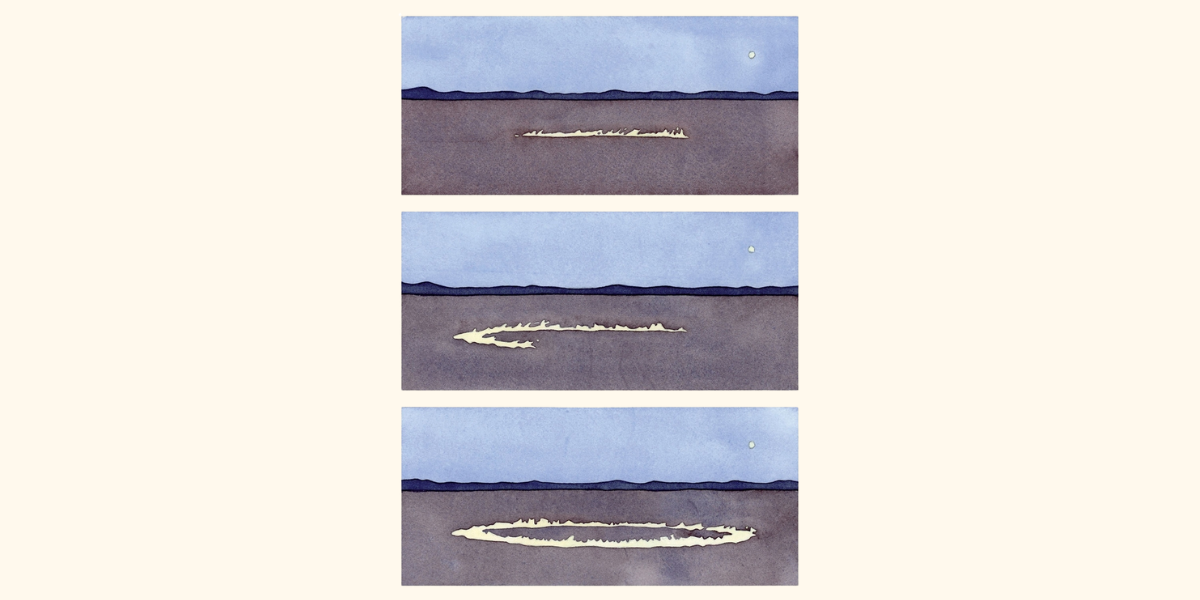

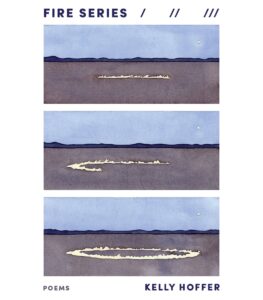

Kelly Hoffer, Fire Series (University of Pittsburgh Press)

Does any of the four elements resist linguistic taming and poetic shaping more than fire? There’s “fire,” the unembellished word, asserting itself in the titles of T. S. Eliot’s “The Fire Sermon” and Brenda Hillman’s Seasonal Works with Letters on Fire, or in technical terms like “fire interval” (the number of years between fires) and “firebreak” (an area cleared of flammable material, impeding wildfires). Fire in all its forms, literal and figurative and symbolic—the consuming ardor of desire, the irreversible incinerations of loss, the flaming swords of Genesis—is the central subject of Kelly Hoffer’s second collection Fire Series.

It’s also the furnace powering her ingenious verbal and visual experiments: erasures with words cremated to an ashy gray, free-verse stanzas that narrow down to one flickering word, pages strewn with slashes like fields of carbonized trees. (As Hoffer explains in an epigraph, one technical definition of “slash” is felled trees, including those “resulting from high wind or fire.”) For a poet of such formal flair, Hoffer recognizes that the most daunting challenge may be restraint, especially in the face of a subject she’d rather leave unbeautiful, the loss of a mother. “how do I protect my mother,” she wonders, from “my lyric tendency / to add the ornament, be it poison or polish or pith”?

Nicole Lachat, The Red We Silk (Southern Indiana Review Press)

“In this and every city,” opens the first poem of Nicole Lachat’s debut The Red We Silk, “I play Charles / Aznavour when I want to swoon / in all my languages.” And Lachat has plenty of languages: Spanish flecked with Indigenous names and diction from her Peruvian mother, French chansons sung by her Swiss father as he washes the dishes, the regional and imperial Englishes of Canada (where she was born) and the United States (where she now lives). Aznavour, the polyglot French Armenian crooner, is one emblem for Lachat’s artistry; another, apparently less glamorous but even more surprising, is the family clerk, its sole self-designated archivist: “I’m the faithful clerk of this / bloodline. I listen through the pleadings, / the arguments. I store it all, every testimony, // so we might go on together.”

Like Lucille Clifton’s memoir Generations and Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard, The Red We Silk follows the growth of a poet’s mind by turning around, looking back decades if not centuries, whether by speaking “To the Ancestors of Túpac Amaru” (the last monarch of the Neo-Inca State) or reenacting the border-crossings of ancestors carrying little more than dread: “I will try to hide this otherness, the thick in my throat / when I say, hel-lo.” Alongside the histories and geographies that created her, Lachat keeps close watch on herself, translating momentary somatic experiences into miraculously accurate language, as in a “Meditation on Touch as Love Language” (“I confess I want to be / touched, to be held between / someone’s lips like a long vowel”), or her “Ode to Synesthesia,” which reads like a Pablo Neruda ode thrown into psychedelic Technicolor:

Call him in by the bright colors

of his name

until the whole room is dripping

golden accent, until

the saffron sound bursts

like a Roman candle in crisp

autumn air.

R. A. Villanueva, A Holy Dread (Alice James Books)

Over three quarters of the poems in R. A. Villanueva’s second collection A Holy Dread are sonnets, sequences of sonnets, or not-so-distant relatives of sonnets with twelve or thirteen lines. Just as many (if not more) of the poems are about parenthood, the feelings fathers share with and discover in young children (love, wonder, reverence), and the feelings they keep contained or meter out incrementally (grief, outrage, anxiety). These two facts aren’t unrelated: in Villanueva’s hands, the sonnet is a perfectly pressurized vessel for parenthood’s competing demands. In a sonnet whose title runs into the poem, “Hallelujah sings the choir and I,” not even an exultant church choir is loud enough to wake the placid daughter who “snores on my shoulder, drools onto my neck.”

Nor can that choir do anything to soothe her sleep-deprived father, worrying over the disasters and trauma-rattled dreams that his generation will inevitably hand down: “I know this / child will learn to curse the sound of my voice.” Villanueva can bend his flexible free-verse lines this way and that, from warm plainspokenness to the patterned symmetries of Catholic liturgy, from soft off-rhymes (“this” / “voice”) to the word-game-like “reverse consonance” pioneered by the Filipino modernist José García Villa. Or he can cede his poems to the next generation of poets in the making, as when asks his son “to tell me about love”: “You love me—and my / mama. I love triceratops.”

D. S. Waldman, Atria (Liveright)

“The thing about art and especially three-dimensional art is I expect it, always, to teach me something.” This sentence comes two pages into D. S. Waldman’s first book Atria, where it articulates a common expectation about poetry, that supposedly sage, often didactic art—and possibly a less common expectation about the art that Waldman is seeing before him as he walks through the galleries of SFMOMA, the congenially abstract mobiles of Alexander Calder. For Waldman, those two arts, the verbal and the sculptural, are more similar than they appear: both are arts of relation, putting lopsided material into unexpected balance, respecting both rigid constraint and chanced-on motion.

And “relation” may be the key word for Waldman’s sonnets, prose poems, and lyric essays, nearly all of which do one or both of two things: 1) speak of relatives and beloveds, the living and the dead, on a first-name basis, or 2) hold the particularities of Waldman’s life up against works of modern art, poetry, and criticism—sources, alternately, of clarity and of obscurity. An essay titled “Low Poetics: A Meditation” begins by describing how Waldman lost the use of his dominant hand—like a Calder sculpture, it was machined into abstraction, technically “mobile” but not on its own accord—and understands his disability through the art and writing of Georges Braque, Jack Halberstam, John Ashbery, and Ben Lerner. The ensuing sequence “Low Poetics” refracts the essay’s subjects and phrases through fifteen Cubist sonnets, ready to bound to a new thought at each split-second line break: “It’s never just / Scarring at the wrist and lost sensation / Nodding along to the empty music / This elegy won’t write itself.”

Christopher Spaide

Christopher Spaide is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Southern Mississippi. His academic writing on modern and contemporary poetry (as well as music and comics) appears in American Literary History, The Cambridge Quarterly, College Literature, Contemporary Literature, ELH, The Wallace Stevens Journal, and several edited collections. His essays and reviews and his poems appear in The Boston Globe, Boston Review, Lana Turner, The Nation, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, Poetry, Slate, and The Yale Review, and he has been a poetry columnist for the Poetry Foundation and LitHub. He has received fellowships from the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry at Emory University, the Harvard Society of Fellows, the James Merrill House, and the Keasbey Foundation; for his academic writing and criticism, he has received prizes from Post45 and The Sewanee Review. Currently, he serves as the Secretary for The Wallace Stevens Society. He is the literary executor for Helen Vendler.