The Synagogue in the Heart of the Delta: Exploring Jewish Culture in Rural Mississippi

Lauren Rhoades on Finding Community and Identity in the Overwhelmingly Christian Deep South

Though we’ve never met, I recognize Barbara immediately. She vibrates with the energy of a woman who does Pilates five days a week and volunteers at the GRAMMY Museum and also makes time for lunch dates with curious Jewish strangers who come to town. Which, of course, she does.

Barbara is wearing a bright cowl neck sweater with silver jewelry. She is a petite woman—much shorter than me—with short brown hair and brown eyes that light up when she smiles. She’s with Nancy, her friend and the president of Cleveland’s local synagogue, Adath Israel. Nancy is reserved but warm, with shoulder-length gray hair and light blue eyes. She is a Delta native and, as I come to learn, an authoritative source on the history of Cleveland’s Jewish community.

After a round of introductions in which I awkwardly decide to shake hands last minute rather than go in for hugs, we walk into the Delta Meat Market together and seat ourselves at a wooden table. Cleveland—located in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, a region dubbed by historian James Cobb as “the most southern place on earth”—seems to have a lot of new construction. On my drive to the family farm turned artist residency where I’m staying this week in a vintage camper shaped like a baked potato, I noticed new buildings popping up along the highway. There’s a Kroger and a Walmart and lots of little local shops. All this activity seems at odds with the general narrative about the Mississippi Delta, which is that economically it’s been dying for years.

I tell Barbara and Nancy that I’m Jewish, that I belong to Beth Israel Synagogue in Jackson, where I take my daughter to Tot Shabbat. I say that I’m a writer, working on a project about what it means to make a home in Mississippi, and I’m doing some research on the history of Jewish communities in the Delta. I say that I want to know about what it was like to grow up here, what Jewish life was like here in its heyday, and what it’s like now.

Even now, asserting my Jewish identity feels like an act of resistance in a place where Christianity is the default assumption.

Truthfully, my increasing curiosity about Mississippi Jews has been somewhat inexplicable even to me. Only after moving to Mississippi did my dormant and neglected Jewish identity seem suddenly important, urgent. I wasn’t in need of spiritual fulfillment. Instead I felt a clinging desire for tradition, familiarity, and comfort in a place that sometimes unmoored me. Even now, asserting my Jewish identity feels like an act of resistance in a place where Christianity is the default assumption and performative acts of Christian prayer pervade public life and politics. In Mississippi, Jews make up less than one half of one percent of the population.

When packing the books that I wanted to bring with me to the weeklong artist residency here in Cleveland, a used first edition of Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table that had been sitting on my bookshelf caught my eye. I had been meaning to read it for years—now I could.

The residency is my first extended trip away from my daughter, who, at one-and-a-half, is weaning off breastmilk, but still likes to nurse at night before bed. My body this week feels her absence. At night, my breasts become hard and swollen. Sitting at the small camper table, with the space heater aimed directly at my feet, I pump milk (which I will later reluctantly pour down the drain) and massage my chest—and read Levi’s book of essays.

Despite having survived Auschwitz, Levi writes with joy, even humor about his life. By the time he published The Periodic Table, Levi had already written two memoirs about his imprisonment in the concentration camps. But in this last collection of essays he barely alludes to his time in Auschwitz. Those unmentioned months cast a dark shadow upon the rich descriptions of his life as a chemist before and after the war. In one passage, Primo Levi describes how the rise of Christo-fascism and discussions of racial “purity” in Europe suddenly activated a defiant Jewish pride within him:

…I had begun to be proud of being impure. In truth, until precisely those months it had not meant much to me that I was a Jew: within myself, and in my contacts with my Christian friends, I had always considered my origin as an almost negligible but curious fact, a small amusing anomaly, like having a crooked nose or freckles; a Jew is somebody who at Christmas does not have a tree, who should not eat salami but eats it all the same, who has learned a bit of Hebrew at thirteen and then has forgotten it.

I relate to that pride, not so much the pride of being “impure,” but the pride of being different from the dominant culture. I do not mean to equate Mississippi to fascist Europe or to say that my religion is under attack in the place I call home (though Christo-fascism is dangerously on the rise in America as a whole, even as the Right weaponizes accusations of anti-Semitism for political gain). In Mississippi, my Jewishness is not threatened by a violent extinction, as Levi experienced, but it is threatened, nonetheless, by an erasure due to invisibility and ignorance.

The truth is, I didn’t always love being a Jew. My Catholic stepmother and her disdain for Jewish people—including and especially my Jewish mother—loomed over my childhood. My stepmother had a codename for Jews—“trees”—that she would use when talking disparagingly about them in public. Trees were cheap, trees were ugly, trees were bookish, trees were greedy. Trees embodied everything that my stepmother—a blonde, effervescent, former cheerleading captain—was not.

After my bat mitzvah at age thirteen, I, too, became a tree in her eyes. My stepmother bought me a small menorah and candles for Hanukkah and forced me to say the blessings on my own as a form of social alienation. She forbade me from going to mass and Sunday breakfast with the family. I wish now that I could have embraced Levi’s defiant pride. Instead, I tried diligently to rid myself of my own impurity, diving headfirst into Christianity. At seventeen, over the course of a year, I converted to Catholicism. By the end of that year, my father and stepmother’s marriage was nearing its breaking point and my new religion failed to give me the sense of belonging that I had once yearned for.

Exhausted by religion and purity and dogma, I occupied myself with other ideas, other identities. Then I found myself in Jackson, Mississippi, smack dab in the middle of the Bible Belt. For the first time, I began to peel back layers and deconstruct defenses. I became curious about my Jewish roots.

*

Nearly as long as there have been white settlers to South, there have been Jews here. Jews fought in the Civil War as Confederate soldiers. Some Jews were enslavers. But it wasn’t until after the Civil War, that larger numbers of Jewish migrants settled throughout the South, first as peddlers, then as established merchants. Though Jewish Southerners may be at “the periphery” of the narrative of American Jewish history and culture, the history of the Jewish South is deeply entangled in the region’s history of Jim Crow and white supremacy. Like any other ethnic group, Southern Jews are not a monolith.

Barbara’s grandparents, I learn, moved from New York to New Orleans, where they opened a jewelry business. Barbara spent the early part of her childhood in New Orleans before her father moved their family to Crawley, Louisiana, to open a jewelry store there. Every week they drove nearly an hour to attend services at the synagogue in Lafayette, Louisiana. (“Oh how I dreaded that drive!” Barbara tells me).

In college, Barbara met her husband Jeff Levingston of Cleveland. They tried to make it for a few years in Nashville where Jeff worked as a lawyer, but opportunities opened up in Cleveland, and the two moved back here in 1973. Coincidentally, the couple were ultimately convinced to move back to Cleveland by Gerald Jacks, the man who would become Jeff’s law partner, and whose family farm became the artist residency where I’m staying now. Gerald and his wife Beth were liberal Democrats who kept a circle of eccentric artist friends. Despite the conservative beliefs of most white people in Cleveland, Barbara felt reassured by the Jacks that she could feel at home here.

Unlike Barbara, Nancy grew up in Cleveland and has attended Adath Israel all her life. As a child, she sang in the choir with her mother, and remembers making not-so-discreet hand signals to her friend who sat facing her in the front row. Nancy’s mother was an Orthodox Jew from Greenwood, where Ahavath Rayim, Mississippi’s only Orthodox congregation, was located. Nancy remembers going to High Holy Day services in Greenwood with her mother. They would have to leave their leather shoes at the door. Inside, the men sat on one side, the women sat on the other. During Passover, her mother kept strict kosher. She would do a deep cleaning, ridding the house of any chametz (leavened bread), and switching out all the dishes. But during the rest of the year, it would have been highly impractical, if not impossible, to keep strict kosher. So, they didn’t.

I don’t get the sense that Nancy and Barbara feel, or perhaps ever felt, on the periphery of Jewish life in America. Judaism was and is a central facet of their social lives. And Jews used to be central to Cleveland’s economic livelihood.

“When we moved to town in the ‘70s, this whole street was made up of Jewish businesses,” Barbara says, gesturing to the restaurant windows which look out onto the main street. On main street now, there are at least four or five clothing boutiques that sell the kind of clothes that appeal to upper-middle class white, Southern, Christian women: billowy blouses and long necklaces and white skinny jeans and suede ankle boots in tones of beige. Trinket shops abound. A children’s clothing shop called Punkin Patch specializes in smocked dresses, Peter Pan collars, and gingham. There’s a well-stocked Christian book and gift shop called The Delta Christian.

It is December, and a massive display of unlit Christmas lights lines the pedestrian walkway. At night the light display glows like an airplane landing strip. There’s a twelve-foot-tall snowman Elvis in lights, a waving Santa, candy canes and reindeer galore. None of the stores here are Jewish-owned now, not even the menswear store called Abraham’s Clothing Shoppe.

“Lebanese,” Nancy corrects me when I ask.

The transformation of downtown Cleveland is symbolic, not just of the exodus of Jews from rural Mississippi, but also of the changing nature of the global economy. The shops on this street used to sell things people actually needed—clothes, shoes, dry goods, groceries, hardware—not just tchotchkes. Now those same necessities can be found at the Walmart Supercenter or one of the dozen dollar stores in the area. Or they can be ordered, of course, from Amazon. An ineffable, but important community component was lost in that economic and social transition. There are fewer opportunities now to meet people of different faiths and ethnicities and races now, when one of the only ways to find community is within a place of worship, i.e. a church. And churches, particularly evangelical ones, tend to be silos, or worse, echo chambers, no matter how welcoming they say they are.

Barbara and Nancy confirm that people in Cleveland used to have a better understanding of what being Jewish meant, of the holidays and the rituals and the beliefs. Nancy gets misty-eyed as she recalls Milton Bird, the synagogue’s choir director, who died not long ago. He was a Baptist minister, but for years he led Adath Israel’s choir on Shabbat services and at important holidays. (“Even if they fell on a Sunday!” Barbara adds.)

Having finished our lunches, we decide to head to Adath Israel, where Nancy and Barbara have offered to give me a tour. As we leave the Delta Meat Market, Barbara points up above the bar to a shelf holding wine and liquor bottles. “Well look at that!” I crane my neck to see what she’s looking at. A white plastic menorah with blue flames barely peeks above the shelf’s railing. “Isn’t that nice,” Nancy says, genuinely touched by the gesture of Hanukkah in a sea of Christmas decorations.

Adath Israel is a solid blonde brick building within walking distance of main street. A green historic plaque lets visitors know that the congregation was organized in 1923, and the temple constructed in 1927 in the “Byzantine style.” An annex where the temple classrooms and kitchen are located was added in 1949-1950.

Barbara has the keys to the temple on a simple metal ring; Nancy and I wait on the side steps while she clicks the key in the lock and pushes open the metal door. I am struck by these small gestures: the keeping of the keys, the opening of the synagogue door, the flicking on of light switches. To care for this building is to care for the memory of those who once filled its sanctuary and classrooms, to hold sacred what once was, what is no longer. The caretaking and preservation of these dying congregations is just another aspect of the invisible labor taken on by a generation of women whose work in the home and the shul—caring for children, husbands, family members—was always taken for granted.

Nancy’s and Barbara’s children left the state as soon as they could, which was college, and they have no intention of ever moving back. Unlike their white Christian peers who went to Ole Miss or Mississippi State, decisions predestined by family loyalties, Jewish Delta teenagers left for big Southern universities outside of Mississippi. They wanted to belong to Jewish fraternities and sororities, to meet Jewish spouses, and take part in Jewish social life. And they did indeed meet Jewish spouses, make Jewish friends, and find jobs that paid multiples more than any position in the Delta might. Nothing aside from family bonds would bring them back to the Delta.

Jewish historian Stuart Rockoff calls this migratory phenomenon “The Fall and Rise of the Jewish South”: the concurrent trends of Jews leaving the rural South for large Southern metropolises like Atlanta and Houston. The American Jewish Yearbook, which Rockoff cites, records an increase of 300% in Atlanta’s Jewish population since 1980, a rate which is nearly ten times the growth rate of the metro area itself.

Though I don’t ask outright, I get the sense that interfaith marriage wasn’t a consideration for Barbara and Nancy’s Jewish Gen-X and millennial children, which strikes me as surprisingly traditional. But this is the South, after all, the region where, on average, more people per capita believe in a god and practice a faith, regardless of what that faith may be. And not surprisingly, if you grow up feeling different from your peers, finding someone who understands the ways in which you are different becomes a powerful bond.

The Adath Israel congregation has dwindled from a membership of fifty families at its height, to just fifteen families now. A few of these “families” consist of widows. Two families live out of state. There are no children.

“The biggest attendance we get now is at funerals,” says Nancy with a wry, sad smile. We are standing inside the sanctuary, which is stunningly beautiful and well-preserved. Ornate stained-glass windows stretch almost from floor to ceiling. On the back wall, an “In Memoriam” plaque holds the English and Hebrew names of deceased congregants, including Nancy’s mother, father, and husband.

We walk to the bimah and Nancy opens the ark, which has stained glass backing and is lit from within. Inside are three torahs, sheathed in white silk with gold embroidery. They are luminous, immaculate. Looking at them, I feel chills raise along my arms and the back of my neck. For Jews, the torah is the holiest of holy objects. So much so, that you cannot touch the parchment with your bare hands; you must use a yad (Hebrew for “hand”) which is a metal pointer, often made of silver, to keep your place as you read. At services, the torah is held in procession around the sanctuary, and people reach out to touch it with a prayer shawl or a prayer book, which is then touched to the lips in reverence.

The Adath Israel temple is currently being rented out by a Pentecostal church, which uses the buildings on Wednesdays and Sundays. “The pastor likes to talk about ‘the Old Testament’ with me,” Nancy confides with a small chuckle. “He considers himself an expert.”

According to the Nancy and Barbara, the Pentecostals in Cleveland recently experienced a schism over whether or not women should be allowed to wear pants. The group who rents out the synagogue decided that women are allowed to pants, though Barbara notes that she’s never seen the pastor’s wife in anything but skirts or dresses.

I start to laugh, but then I’m reminded of a fabulous and heartbreaking book I recently finished: Casey Parks’s Diary of a Misfit: A Memoir and a Mystery. In it, Parks writes about growing up and coming out in a small, deeply religious community in Louisiana, and her search to learn more about the mysterious local figure of Roy Hudgins, who her grandmother once described as a “woman who lived as a man.” For years, Parks, a journalist, tracked down information about Roy, who had lived and died in a small town in Louisiana as an outsider, trying to belong, but never quite able to fit in. In one instance, Parks learns that Roy was kicked out of a Pentecostal church for wearing a cap and pants. The church members said Roy needed to wear a dress. They called him a “morphodite,” and cited an obscure passage from Deuteronomy—the same one that surely caused the schism among the Pentecostals of Cleveland—about how men and women who wear the other gender’s garments are abominations to God.

Even as the Jewish community in Mississippi dwindles, these days I find immense satisfaction in sharing my Judaism with my daughter.

Diary of a Misfit is a reminder of how inhospitable religion can be for women and queer people. Parks, who attended Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi, experienced her own share of religious trauma in the evangelical church where she grew up, memories that haunt her throughout her research on the life of Roy Hudgins.

As much as I love the South, I loathe the closeminded sects of Christianity that have rooted here like parasites in the body of a willing host. I hate the bigots who cloak themselves with Bible verses, mistaking prejudice for righteousness.

I have two friends—one from Mississippi, one from Alabama—who in the years since we have known each other, have both come out as transgender. Both of them bear the scars of religious trauma. They come from devout Evangelical families in small, homogenous rural communities. As children, they attended Vacation Bible School; their lives revolved around church and youth group and worship and Bible study. Coming to terms with their own identities involved a painful and gradual unlearning of ingrained beliefs.

My friends no longer live in the South. One moved to the West Coast and one moved to the East. They have created successful careers and have found partners and communities who love and embrace them for who they are. They are no longer hiding their true selves. But they still feel the pain and alienation in being cut off from the people who were once their whole world. They are exiles, pining for home, but unable to return.

Even after all the religious trauma she experienced, Park writes: “I realized that losing church had been the most painful thing I’d ever endured.” Comfort and cruelty can grow from the same root.

In spite of the religious turmoil I experienced, the reformed Judaism of my childhood was a welcoming faith. At Passover, my family put an orange on the seder plate to represent Miriam’s contribution (and by extension all women’s contributions) to the Jewish faith. For a number of years, my grandfather, the son of a Conservative rabbi, lived on an inter-faith commune in New Mexico. We visited him there at least a couple times a year, participating in Sufi dances, Buddhist chants, and Jewish hippy matzah meditations in which we were instructed to let the dry, unleavened, flavorless cracker melt on our tongues. My grandfather still decorates his home with Tibetan prayer flags, statues of the Buddha, and Judaic art. For someone to be Jewish and a practicing Zen Buddhist did not seem in the least bit strange to me, even while I was aware that going to Catholic mass and making the sign of the cross whenever I was with my father and stepmother was deeply at odds with being Jewish.

I wonder if this syncretic version of Judaism would seem odd or off-putting to my new friends at Adath Israel. For one, Jews have always held a tenuous position in white society, but even more so in Southern white society. Jewish Southerners had to emphasize their similarities and downplay their differences from their Christian neighbors as a matter of social and economic—and sometimes literal—survival. I detest the term “Judeo-Christian,” but I imagine it has been a useful one for Jewish Mississippians, a way to show unity with their Christian neighbors.

Now, for Adath Israel congregants, “survival” holds different connotations, simply because the congregation has dwindled so. In recent years, before the rabbi from Memphis retired, many Christians attended services here—they liked the rabbi’s sermons more than their preachers’. Perhaps these same Christians will help to carry the synagogue’s legacy forward. Barbara and Nancy are grateful to their Pentecostal tenants for caring for the building. They no longer worry about checking the building for roof leaks the morning after a bad rain storm, because they know the church members will be there, keeping an eye on things.

Before we leave, Nancy and Barbara show me a wall of framed confirmation class photos in black and white and sepia tones. Nancy points out her own class photo. Eleven Jewish teenagers—nine girls and two boys—stand on the bimah around Rabbi Landau who has on thick, black-rimmed glasses. The girls wear white dresses and slim white heels, and the boys wear white suit jackets with black ties and black pants. A young Nancy smiles shyly in the back row, her long blonde hair pulled back from her face. Like all the other girls, she holds a small bouquet tied with white ribbon. Standing back, I see that Nancy’s confirmation class is one of the larger ones. In subsequent years, the number of confirmands in the photos dwindle. In one photo on the wall, only one young woman stands next to the rabbi.

Even as the Jewish community in Mississippi dwindles, these days I find immense satisfaction in sharing my Judaism with my daughter—lighting the Shabbat candles, or reading a Hanukkah picture book together, or singing silly songs at our temple’s monthly Tot Shabbats. Rather than allowing religion to limit my daughter’s worldview, to narrow her definitions of right and wrong, good and bad, I want our traditions to broaden her view of herself. I want her to feel connected with Jews in Mississippi, with our Jewish family members scattered around the country, and with the Jewish diaspora dispersed throughout the globe.

Outside the building, I take a photo of Nancy and Barbara standing beneath the Adath Israel historical marker, and they take one of me. Before I leave, Barbara tells me to wait, then hurries to her car to grab something. She brings back a freezer bag full of homemade morning glory muffins. “These should last you the rest of the week,” she says. They are dense and full of raisins and shredded carrots, and I will indeed eat them throughout the rest of my stay, popping them in the camper’s tiny toaster oven just as she instructed, feeling nourished by the warm offering of friendship and care. We hug and I thank her, promising to come back one day for holiday services.

As Barbara pulls away, I take one last look at the synagogue. How strong and sturdy and quiet it seems in the late afternoon light. When the builders first laid the brick nearly a century ago, they must have imagined it would last forever.

__________________________________

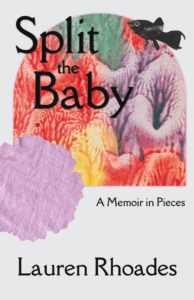

Split the Baby by Lauren Rhoades is available from Belle Point Press. Featured image: Hamhari Brown, used under CC BY-SA 3.0

Lauren Rhoades

Lauren Rhoades is a writer, editor, and grantmaker living in Jackson, Mississippi. Originally from Denver, Colorado, Lauren has served with AmeriCorps, started Mississippi's first fermentation company, and helmed the Eudora Welty House & Garden. She is now director of grants at the Mississippi Arts Commission and a host of MPB's The Mississippi Arts Hour. In 2022, Lauren founded Rooted Magazine, an online publication dedicated to telling unfiltered stories about what it means to call Mississippi home. She holds an MFA in creative writing from the Mississippi University for Women. Her first book, Split the Baby: A Memoir in Pieces, was published in June 2025.