The Surprising Stories Behind the Pen Names of 10 Famous Authors

Including Some You May Not Have Known About

Some authors become so iconic that they cease, in some sense, to be people—especially once they’re dead, and have passed securely into the realm of our collective imagination. But there’s much to be gained from digging a little deeper into those writers, or at the very least, scratching off that first surface: the names (and personas) they invented for their writing careers. Lots of authors have pen names, of course, many more than I’ve included below, and I’ve intentionally strayed from many of the most obvious ones—if you’re reading this space, odds are good that you already know about George Sand and George Eliot, Lewis Carroll and O. Henry. Instead, I’ve collected a few great stories behind legendary literary pseudonyms that you may not have heard about yet.

Ulf Andersen

Ulf Andersen

James Salter, née James Horowitz

Famously, James Salter flew fighter jets in the Korean War. In 1956, he published his first novel, The Hunters, which was based on his experiences and the journal he kept during his years in the air. When it first appeared, as a serial in Collier’s, Salter was still in the Air Force, stationed in Germany. As Nick Paumgarten reported in 2013 New Yorker profile:

One night, another veteran of the Yalu, a pilot named Mattson, who was reading Collier’s, said to Salter, “Hey, did you read this thing? This story here about Korea?” Salter feigned enough curiosity to deflect attention from himself. He was less interested in Mattson’s opinion of the work than in not being connected with it. “Let me read it when you finish,” he said.

The author’s name would not have aroused Mattson’s suspicion. Salter’s given name was James Horowitz. While writing The Hunters, he had chosen James Salter as a pen name to hide his identity from his colleagues and superiors. “There was contempt for writers,” he said.

“It was one of a long list of names I had written down,” he told Paumgarten. Another was John Eden. “And some of them were pretty bizarre. I thought, Don’t get carried away here, just make it something simple, so that it doesn’t draw a lot of attention to itself. And I picked it for that reason. It was an arbitrary and, I think, not tremendous choice.”

But the pen name eventually became something more than an arbitrary choice, a way to avoid the writer’s stigma. He moved to New York. He began life as a writer. “He was Salter now, not Horowitz,” Paumgarten writes.

What started as a “ring name,” as he called it, became a new identity. “I wanted to distance myself from my past, naturally,” he told me. “I was living a life of being Horowitz and being Salter, and I said, I’m going to switch over completely. I didn’t see any problem with it. My mother did.” He has also said that he didn’t want to be thought of as another Jewish writer from New York; there were enough of those. Horowitz, for years, went unacknowledged. When a Times Magazine profile in 1990 revealed the name change, he was upset. “That was like coming out for him,” Peter Matthiessen, a longtime friend, said.

In graduate school, I had a class with Salter; outside of it, I watched two of my Jewish classmates have a heated argument—in the end, one of them had to leave the party—over whether it was acceptable, or moral even, for Salter to have changed his name, to have hidden his Jewishness. It was what he had to do, one of them said. It was a betrayal, said the other.

In the Jewish Review of Books, Rich Cohen wrote:

Salter speaks to all those who intermarried and joined the club, donned white bucks and seersucker, who, lost in Sag Harbor and Hilton Head, have spent years trying to slip the shackles as Houdini, né Weiss, slipped his shackles before the multitudes. Between Salter’s most elegant lines, I can still hear Horowitz scream. . . Salter suffered from a disease diagnosed by the early Zionists, for whom a Jewish nation—what if Horowitz had been flying a Mirage over Sinai instead of an F-86 over the Yalu?—was the cure. Simply put, Salter believed what they told him at West Point—about the world and about himself. He internalized it, then shaped himself around this conception. If he wanted to be a great pilot and a great American writer, he could not do it named Horowitz.

I hope that’s not true—and at least we know it no longer is—but either way, he certainly became that great American writer.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Toni Morrison, née Chloe Ardelia Wofford

I have to admit, I had no idea that Toni Morrison was a pen name—but it’s true. The “Toni” came from her saint’s name, Anthony, which she took at 12 after converting to Catholicism. Toni soon became her nickname. “Morrison” was her first husband’s name—they married in 1958 and divorced in 1964. “To this day,” wrote Boris Kachka in a 2012 profile of Morrison, “she deeply regrets leaving that now world-famous name on her first novel, The Bluest Eye, in 1970.”

“Wasn’t that stupid?” she says. “I feel ruined!” Here she is, fount of indelible names (Sula, Beloved, Pilate, Milkman, First Corinthians, and the star of her new novel, the Korean War veteran Frank Money), and she can’t own hers. “Oh God! It sounds like some teenager—what is that?” She wheeze-laughs, theatrically sucks her teeth. “But Chloe.” She grows expansive. “That’s a Greek name. People who call me Chloe are the people who know me best,” she says. “Chloe writes the books.” Toni Morrison does the tours, the interviews, the “legacy and all of that.” Which she does easily enough, but at a distance, a drama-club alumna embodying a persona—and knowing all the while that it isn’t really her. “I still can’t get to the Toni Morrison place yet.”

“Myself is kind of split,” she told The Guardian the same year. “My name is Chloe. And the rest is . . . that other person.”

Pablo Neruda, née Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto

Pablo Neruda, née Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto

Pablo Neruda changed his name to avoid bringing shame and destruction to his entire family—or just to get his father off his back. His earliest publications bore his own name, but as soon as he began to get serious about writing, he also became Pablo Neruda. “I don’t remember,” Neruda once said when asked why he’d chosen the pseudonym.

I was only thirteen or fourteen years old. I remember that it bothered my father very much that I wanted to write. With the best of intentions, he thought that writing would bring destruction to the family and myself and, especially, that it would lead me to a life of complete uselessness. He had domestic reasons for thinking so, reasons which did not weigh heavily on me. It was one of the first defensive measures that I adopted—changing my name.

Many have speculated that he chose the name as an homage to Czech poet Jan Neruda, to which the Chilean shrugged:

I’d read a short story of his. I’ve never read his poetry, but he has a book entitled Stories from Malá Strana about the humble people of that neighborhood in Prague. It is possible that my new name came from there. As I say, the whole matter is so far back in my memory that I don’t recall. Nevertheless, the Czechs think of me as one of them, as part of their nation, and I’ve had a very friendly connection with them.

So, maybe?

John le Carré (David John Moore Cornwell)

John le Carré (David John Moore Cornwell)

Of all the writers on this list, John le Carré probably has the coolest reason for using a pseudonym—spies can’t use their own names when they publish books. I mean, obviously! He wrote his first novel, Call for the Dead, while an MI5 agent, but it didn’t print until he had moved to MI6. As le Carré explained:

I was what was politely called “a foreign servant.” I went to my employers and said that I’d written my first novel. They read it and said they had no objections, but even if it were about butterflies, they said, I would have to choose a pseudonym. So then I went to my publisher, Victor Gollancz, who was Polish by origin, and he said, My advice to you, old fellow, is choose a good Anglo-Saxon couple of syllables. Monosyllables. He suggested something like Chunk-Smith. So as is my courteous way, I promised to be Chunk-Smith. After that, memory eludes me and the lie takes over. I was asked so many times why I chose this ridiculous name, then the writer’s imagination came to my help. I saw myself riding over Battersea Bridge, on top of a bus, looking down at a tailor’s shop. Funnily enough, it was a tailor’s shop, because I had a terrible obsession about buying clothes in order to become a diplomat in Bonn. And it was called something of this sort—le Carré. That satisfied everybody for years. But lies don’t last with age. I find a frightful compulsion towards truth these days. And the truth is, I don’t know.

Trust a spy to keep the real story close to his chest. Well, at least he didn’t go with “Chunk-Smith.”

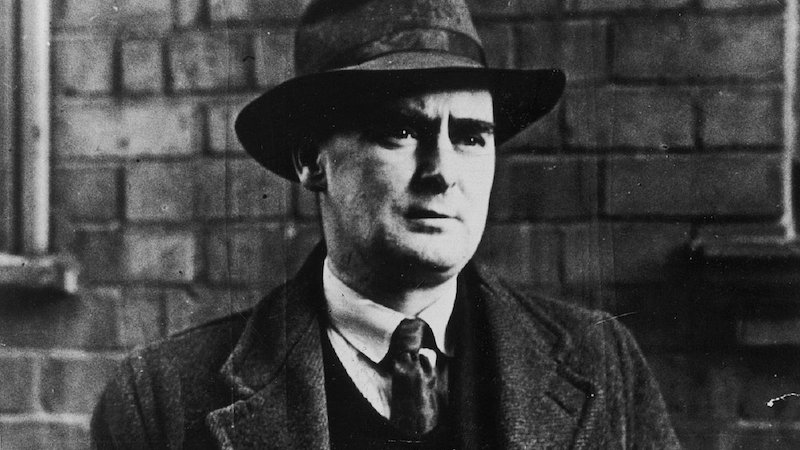

Flann O’Brien (Brian O’Nolan)

Flann O’Brien (Brian O’Nolan)

Flann O’Brien may be O’Nolan’s most famous pseudonym, but it’s not his only one. As Flann O’Brien, O’Nolan wrote At Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman, but he also wrote for The Irish Times as Myles na gCopaleen (“Miles of the Ponies”). In his introduction to The Complete Novels of Flann O’Brien, Keith Donohue writes:

Myles was a cross between the comic stage Irishman embodying every known stereotype and a savage critic of clichéd language and thinking, bureaucracy, mendacity, and other social foibles. To the intelligentsia of Dublin, however, and habitués of the pubs, Myles was a real human being. He’s that man in the corner nursing a pint, the fellow under the hat, the person otherwise known as Brian O’Nolan. On occasion, all three persons met in Cruiskeen Lawn, such as this encounter stimulated by the republication of At Swim-Two-Birds. In his thick mock Dublin accent, Myles says:

There’s stories going round that Flann O’Brien and my good self are wan and the same pairson. I know my own know about that leaper. People has said that I have receded under many disguises in many papers, but nobody on or under this world knows what I have written or can declare on oath what I have not written.

But why the pseudonyms at all? First, as Donohue points out, O’Brien was very private. Secondly, the multiple psedonyms let him interact with himself in a public forum (he actually started doing this in college, with a whole different set of pen names). Finally, O’Nolan was a member of the Irish civil service, and as such was not permitted to publish any political views (so in effect any literary work at all) under his own name. He got around that—and around it, and around it . . .

Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel)

Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel)

Everyone knows that Dr. Seuss is a pen name—I mean, look at it—but not everyone knows where it came from (or at least I didn’t, before I began researching this list). Well, I’m here to tell you: it came from gin. More specifically: getting caught drinking gin in his room at Dartmouth with his friends. Nowadays you might barely get a citation, but this was 1925, and Prohibition was in full swing. He lost his editorial gig at the Dartmouth humor rag, the Jack O’Lantern, “but curiously,” as Jessica Contrera put it in The Washington Post, “many drawings in his style still appeared in the next edition. They were signed with pseudonyms that an eagle-eyed reader might recognize as oblique historical references—L. Burbank, Thos. Mott Osborne, D.G. Rossetti, L. Pasteur—but also, ‘Seuss’.”

But more importantly: you’re pronouncing his pen name wrong. It’s not “Suce.” It’s “Soice”! That is, apparently, the German way. His Dartmouth buddy and Jack O’Lantern co-conspirator Alexander Liang later immortalized the misconception in a casual quatrain:

You’re wrong as the deuce

And you shouldn’t rejoice

If you’re calling him Seuss.

He pronounces it Soice.

SOICE. Just let that sink in for a while.

James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon)

James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon)

This is also well-known to be a pen name, but I love the story: counterintelligence analyst and experimental psychologist Alice Sheldon saw a jar of Tiptree marmalade at the supermarket one day, and decided, just for fun, to use it to send out some science fiction stories she’d been working on. She soon became a star and a cult hero, despite remaining anonymous behind the pseudonym (all correspondence went to a P.O. Box in Virginia). Some fans thought Tiptree was secretly J.D. Salinger. Some thought he was Henry Kissinger. Some thought he was a woman. In the introduction to Tiptree’s 1975 collection Warm Worlds and Otherwise, Robert Silverberg wrote: “It has been suggested that Tiptree is female, a theory that I find absurd, for there is to me something ineluctably masculine about Tiptree’s writing. I don’t think the novels of Jane Austen could have been written by a man nor the stories of Ernest Hemingway by a woman, and in the same way I believe the author of the James Tiptree stories is male.” Ha ha, you might think, but of course, Sheldon was a top tier writer, and was writing as a man. Introducing a selection of Tiptree’s correspondence with Joanna Russ, Nicole Nyhan wrote:

As Tiptree, Alice Sheldon exchanged lively and intimate correspondence with some of the most important writers of speculative fiction. Over time, James Tiptree, Jr. took on a life of his own, developing long-standing relationships. While as a story writer Tiptree was known for deploying short bursts of robust prose, in his letters Tiptree was effusive and gregarious, a comic performing with preternatural bravado. An ingratiating and charmingly self-deprecating correspondent, Tiptree was alternately a compassionate listener, educator, contrarian, and avid advice giver, often picturing himself as a wizened old sage and referring to himself as “Uncle Tip.” With women, he was also an audacious flirt.

Sheldon’s true identity was discovered in 1976, after, according to Dave Itzkoff, “she let it slip in a letter from Tiptree to a fanzine editor named Jeffrey D. Smith that Tiptree’s mother, already known by devoted readers to be an African explorer, had died.” All it took was a little digging among the obituaries for Smith to find her out. He wrote back: “Word is spreading very fast that your true name is Alice Sheldon.” She replied: “Yeah. Alice Sheldon. Five ft 8, 61 yrs, remains of a good-looking girl vaguely visible, grins a lot in a depressed way, very active in spurts.”

Anne Rice, née Howard Allen Frances O’Brien

Anne Rice, née Howard Allen Frances O’Brien

Anne Rice has a pair of well-known pseudonyms—A. N. Roquelaure and Anne Rampling—used primarily for her erotica. “I wanted the pen name personally so that I could feel absolutely free to write the best and most exciting erotica possible,” she wrote. “Authenticity was key. No half measures. Also I didn’t want my father to know about the books.” As for the meaning behind “A. N. Roquelaure”: “Roquelaure was a Frenchman who popularized a certain kind of cloak, which became known as a “Roquelaure” in the 19th century and possibly before. I chose the name A.N. Roquelaure because it means Anne with a cloak.” Clever! But did you know that she wasn’t born “Anne Rice” either? Her original name was Howard. Yes: Howard. “My birth name is Howard Allen because apparently my mother thought it was a good idea to name me Howard,” Rice once said. “My father’s name was Howard, she wanted to name me after Howard, and she thought it was a very interesting thing to do. She was a bit of a Bohemian, a bit of mad woman, a bit of a genius, and a great deal of a great teacher. And she had the idea that naming a woman Howard was going to give that woman an unusual advantage in the world.” Rice did not agree, and on the first day of school, told her teachers her name was Anne, legally changing it in 1947. She married Stan Rice in 1961 and took his last name. So I wouldn’t exactly call “Anne Rice” a pen name—but it is certainly a self-constructed one.

Liza Matthews

Liza Matthews

bell hooks, née Gloria Jean Watkins

In 1978, when she published her very first book of poems, Gloria Jean Watkins adopted the name of her maternal great-grandmother Bell Blair Hooks. But of course, her pen name is not Bell Hooks—it’s bell hooks. Asked why she styles her name in lowercase, hooks said:

When the feminist movement was at its zenith in the late 60’s and early 70’s, there was a lot of moving away from the idea of the person. It was: let’s talk about the ideas behind the work, and the people matter less. It was kind of a gimmicky thing, but lots of feminist women were doing it. Many of us took the names of our female ancestors—bell hooks is my maternal great grandmother—to honor them and debunk the notion that we were these unique, exceptional women. We wanted to say, actually, we were the products of the women who’d gone before us.

“It’s primarily about an idea of distance,” she told Tricycle in 1992. “The name “bell hooks” was a way for me to distance myself from the identity that I most cling to, which is Gloria Watkins, and to create this other self. Not dissimilar really to the new names that accompany all ordinations in Muslim, Buddhist, Catholic traditions.” But, she says, everyone in her “real” life knows her as Gloria. “I live in a city of 12,000 people where most of them don’t have a clue about who bell hooks is for the most part, or where someone asks ‘Is bell hooks a person?'” she told the New York Times in 2015. “There is humility in the life that I lead, because one thing about having my given name, Gloria Jean, which is such a great Appalachian hillbilly name, is that I’m not walking around in my daily life usually as bell hooks. I’m walking around in the dailiness of my life as just the ordinary Gloria Jean.”

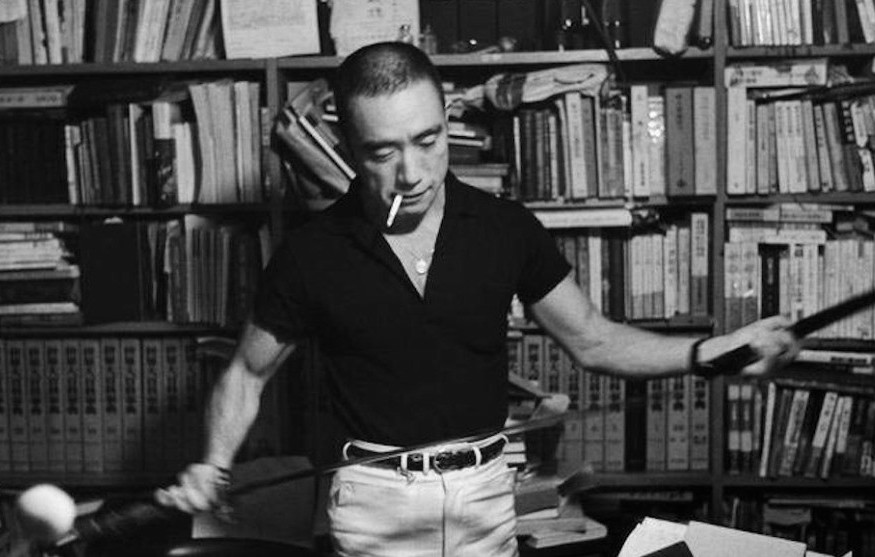

Yukio Mishima, née Kimitake Hiraoka

Yukio Mishima, née Kimitake Hiraoka

Mishima was always a romantic, so no one should be surprised that his pen name came from a scenic train ride. He was going to Shuzenji to meet the editors of the literary magazine Bungei Bunka, after his teachers had sent them one of his stories, “Forest in Full Bloom.” They wanted to publish it, and it would eventually appear in book form in 1944, attributed to Yukio Mishima. His biographers Naoki Inose and Hiroaki Sato have described it this way:

To go to Shunzenji from Tokyo, you first take the train on the Tōkaidō Line and go to Mishima, where you switch to a local line south. So the names Mishima and Yuki (“to go” or “bound to”) came naturally. Yuki, which also means “snow,” was appropriate as well in view of the permanent snow adorning the top of Mt. Fuji, which you saw soaring northwest from the train window. The “o” of Yukio is a common suffix to male names.

They also point out that Japanese writers and poets frequently used pen names, and that considering the fact that his father had “vowed not to allow his son to dabble in literature, back in the household, the adoption of the pen name probably relieved Mishima of certain anxieties.”

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.