There was a man I saw once or twice a week in the hot tub at the YMCA who talked boisterously, as if he were in a bar, as if he wanted everyone to know his business. His voice was too loud for the intimate setting, where barely clothed strangers sat together in hot water, skin cells sloughing off, simmering in the steaming cauldron. He talked about his fiancée, whom he was bringing over from Russia, about the crazy red tape she had to untangle to get her visa. “She’s 25,” he said, though he looked late 40-ish. He was fat, though handsome, with a fine nose and good straight teeth. He wore gold-rimmed glasses that never fogged. The fat man had been growing less fat over the past few months, perhaps because he didn’t want his Russian bride to be shocked when she arrived.

I disdained this man, but my feelings were disproportionate to my annoyance, and so I wondered, what aspect of myself did I see reflected in him? What self-loathing was I projecting onto his large pale torso? Maybe he irritated me because he participated in an economy in which women trade youth, beauty, and sex to men with means for a life free from poverty. Maybe I disliked his naiveté, his belief that love might motivate his Russian fiancée, not economic gain. Or maybe his bid for companionship was too public, too much on display, and thus forced me to consider my own aloneness.

When the hot tub broke and was closed for a few weeks, I didn’t see the fat man for a while, and part of me missed him, or missed the guilty pleasure of disliking him. I’d cultivated an elaborate disinterest around his frequent talk of the Russian fiancée. I’d strive for an expression that conveyed, I’m not listening. You can’t impress me. I’m preoccupied with my own important contemplations.

The Baths at Caracalla, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1899

The Baths at Caracalla, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1899

In ancient Rome, bathing was practically an art form, a religion. After temples, bathhouses were the most common buildings. A fourth-century census recorded 856 public bathhouses for Rome’s million or so citizens, which would be the equivalent of 900 public bathhouses in Dallas, Texas, today. The Baths of Caracalla, a 27-acre complex that took 9,000 laborers five years to complete, exemplified Romans’ devotion to bathing. It included sports fields, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, gardens, fountains, and a four-story bathhouse that accommodated 1,600 people, with massage rooms, saunas, perfumeries, and a hair salon. The interior walls were adorned with mosaics and gilded carvings, and a hundred alcoves for statuary. There was a hypocaust (literally fire underneath) to warm the tiled floors, and to heat the tub waters, 50 furnaces burned ten tons of wood daily.

On a typical day in ancient Rome, a tintinnabulum rang to summon men and women to the baths—mixed-sex bathing was common. Entrance fees were free or low, so the poor could bathe, too. They soaked in the warm tepidarium or the hot caldarium, or dipped into the bracing frigidarium, all while being entertained by jugglers, acrobats, musicians, and poets. Vendors hawked wine, pretzels, cake, eels, and quail eggs. You could hire a depilator to pluck unwanted hair, or someone to oil, sand, and scrape your skin. All this bustle created a cacophony that “could make you hate your own ears,” wrote Seneca, the first-century rhetorician. Musclemen pumping weights emitted “squeaking, squealing sound[s].” Masseuses’ slapped flesh, pickpockets were noisily arrested, and bathers yelped from having hair yanked from their armpits. “Sausage sellers, the pastry bakers and the barmen” cried their wares, and there was always a man, Seneca bristled, “who likes to hear himself singing in the bath.”

Aside from giving him headaches, Seneca believed that communal bathing inspired “sexual licentiousness and moral delinquency,” which was probably true. The Roman baths were designed for voluptus—delights of the flesh. Erotic frescoes at a Pompeii bathhouse depicted people having sex in graphic detail, and an epigram at the entrance to the Baths of Caracalla read: “Baths, wine and sex spoil our bodies; but baths, wine and sex make up life.”

*

My first hot tub experience was meant to be erotic. In college in the early 1980s I rented an hour at Heavenly Hot Tubs in Northampton, Massachusetts, the grand finale to a night I’d planned for my second anniversary with David. I cooked a gourmet dinner, bought tickets to see the great French mime Marcel Marceau, and splurged on the hot tubs. That night David stopped for a drink after work, then another, and another. By the time he came home the dinner was congealed. At Marceau’s performance, in the pin-drop quiet auditorium, David loudly sneered. A talented but unsuccessful musician, he was annoyed that the audience loved this performer who made no sound. I stood and walked out of the auditorium, then hid outside to see how long it would take him to realize I hadn’t just gone to the ladies’ room. I tried to recover the night at Heavenly Hot Tubs, but David complained the water was too hot. It took me another year to realize, oh, he’s an alcoholic, and soon after, I can’t save him.

*

Romans bathed for pleasure, but also to follow the medical wisdom of the time. Pliny the Elder in the first century, and Celsus, a century later, recommended baths for gout, itching, palsy, “complaints of male organs,” gangrene, rabies, epilepsy, psoriasis, small pustules, and lice in the eyelashes. Sitting in the tub at the Y, I’ve often wondered about the ingredients of the human soup. Urine leakage, for sure, perhaps pus from suppurating boils, saliva, fecal particles, hair and the follicles attached to them, toe shreddings, dirt from under fingernails, nose and throat mucus, and oil from the thousands of sebaceous glands beneath our skin—as many as 900 on the face alone, all secreting waxy sebum. Dead skin cells slough off. Each of us sheds up to 500 million skin cells daily; we grow a new suit of skin each month. Belly button lint is emancipated by the roiling water, especially since there were always more men at the Y and belly button lint is a male phenomenon, as chemist George Steinhauser discovered in his four-year study of “navel fluff.”

Marcus Aurelius, the stoic emperor, wrote, “This bathing that usually takes up so much of our time, what is it? Sweat, filth; or the sordes of the body.” Sordes is the Latin root of sordid—“an excrementitious viscosity . . . all base and loathsome.” Samuel Pepys, the 16th-century diarist, who bathed in the thermal waters at Bath, England, wrote, “Methinks it cannot be clean to go so many bodies together into the same water.” A 19th-century traveler to a Persian bathhouse wrote that if people wanted to become clean, the bath was “the worst place” to go, the water “glutted with abominations . . . rats and black-beetles and horrible insects.”

The human soup is a teeming broth, which must mean I have a high threshold for disgust, combined with a weakness for corporeal pleasure. One night in a hot tub at a sports club in Missouri, where I lived for seven years, the jets whipped a froth on the surface of the water that broke into foamy islands. One island of foam had caught in its merengue several short black squiggly hairs. At that point, I should have fled the tub, but it felt so good that I simply cupped my hand beneath the foam and flung it—with its payload of hairs—onto the tiled floor.

*

Near the end of the Roman Empire, the baths fell into disrepair; it was difficult to maintain the sophisticated heating and plumbing systems in the midst of political turmoil. Sieges by Vandals and Huns damaged the aqueducts that funneled water to the dozen imperial bathhouses and 926 public baths, and in 537 AD the Ostrogoths completely destroyed them. Without water, 90 percent of Rome’s population left the city. Within two decades not a single imperial bath complex survived.

“We literalize the metaphor: warm the body, warm the heart and soul.”

The Goths attacked the bathhouses, but Christians attacked the idea of bathing. In the fourth century, the Mother Superior of a convent warned that a “clean body and clean dress” signified an unclean soul. Christian ascetics practiced alousia, “the state of being unwashed.” Thirteen-year-old St. Agnes died in 304 AD having never taken a bath, and St. Fintan of Clonenaugh was said to bathe once annually, just before Easter. St. Anthony never washed his feet his entire life, and St. Francis of Assisi thought “dirtiness” a sign of holiness. In the sixth century, St. Benedict didn’t bathe during his seven-year pilgrimage through France, Italy, Germany, and Spain, for which he earned the honorific “The Great Unwashed.”

Architecture symbolizes the ethos of its time, evidenced after the fall of the Roman Empire when the decadent, now crumbling bathhouses were transformed into churches. Under Pope Pius IV, the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian—the largest bath complex in Rome, covering 32 acres—were remodeled into a church and monastery, Santa Maria degli Angeli. Michelangelo, who oversaw the project, incorporated into his design the original magnificent architecture of the bathhouse.

*

Wherever there is hot water, I go in. In Livingston, Guatemala, where boiling water seeps from the fissures of a cliff along the Rio Dulce, the captain on our boat trip to a manatee preserve idled his craft so we could swim in the thermal waters. In Yellowstone Park, surrounded by snowcapped mountains, I sat in an eddy of a rushing river where hot water bubbled up from some molten core, wearing only my bra and underwear. At the Sands Motel in Houghton Lake, Michigan, in the 1990s, I sat in a hot tub on a cool October night with Steve, my boyfriend of four years, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Steve had tumors all along his spine by the time doctors discovered the disease, and he was in constant pain. That night in the tub—gazing at the veil of the Milky Way, warm swirling water soothing Steve’s aches—was the single moment of physical pleasure for Steve in 18 months, from the time he was diagnosed until the day he died at 31.

*

After prayer failed to relieve St. Augustine’s sadness over his mother’s death, he thought to “go and bathe” because he’d heard that bathing “drives the sadness from the mind.” A recent study in France found that a hot bath more successfully eased anxiety than paroxetine (brand name, Paxil), a prescription antidepressant. In that study, a couple hundred people aged 18 to 74 who’d been diagnosed with General Anxiety Disorder were divided into two groups. One group took a daily ten-minute “bubbling” bath in warm mineral waters, followed by a three-minute shower, and then a ten-minute underwater back massage, while the control group took 20 milligrams of paroxetine. After 21 days, the bath group showed “significantly lower” scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale than the Paxil group.

Other studies have shown that “water bathing” decreases stress hormones (cortisol), and helps balance serotonin levels. Recently researchers in Virginia found “hydrotherapy” beneficial in treating depression; cold water, they found, increases the production of endorphins. Still, it’s hard to imagine the ice baths given to patients in mental institutions in the early 20th century as anything but cruel. According to a medical text of the time, the patient was immersed every three hours in “a great tub of cold water, with its lumps of ice clinking against its sides” during the “20 minutes of torture.”

A pair of Yale researchers found that hot baths can ease loneliness. “Feelings of social warmth or coldness can be induced by experiences of physical warmth or coldness,” they wrote. Their study showed that people who rated higher on loneliness scales bathed or showered more often, longer, and with hotter temperatures. Bath-taking, they suggested, is “an unconscious form of self-therapy,” in which people substitute physical warmth for “social warmth.” We literalize the metaphor: warm the body, warm the heart and soul.

*

One night at the Y, I saw a lovely auburn-haired woman swimming in the “therapy” pool next to the hot tub, which is half the size of the main pool. The woman splashed and played like a ten-year-old. She wore a two-piece bathing suit as if at the beach, unlike my one-piece Speedo or the swim-dresses favored by older women. The young woman had a distinct mole on her cheek, which was interesting rather than unfortunate because she was so pretty, with doe-eyes and sensual lips, alabaster skin. She had a Russian accent, but spoke English well. She was the fiancée of the fat man who’d slimmed down; he was now bronzed and healthy looking, though flabby around the waist. He was not her aesthetic match and I couldn’t help but wonder, is she disappointed? She seemed ecstatic to be swimming at this YMCA, lounging in the hot tub. I felt a little sad about the situation—I imagined that she had fled some remote oppressive region in Russia only to wind up with a man twice her age who took her to the Y. I wished he’d taken her someplace better.

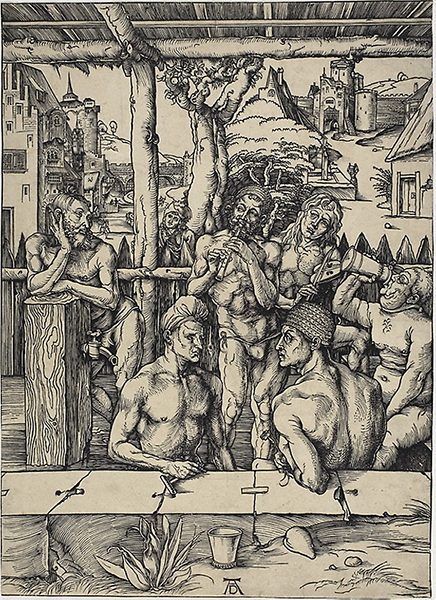

The Bath House, Albrecht Dürer, c. 1496

The Bath House, Albrecht Dürer, c. 1496

In the Middle Ages, public baths in London, called “stewes,” were often little more than brothels, some with built-in galleries for voyeurs. In France, Germany, and England in the mid-1500s, the stewes were ordered closed to halt the epidemic of syphilis—“the great pox”—believed to originate in the baths. Francis I, the King of France, destroyed the public baths in Paris in 1538 before he himself succumbed to the disease. Another epidemic, the bubonic plague, kept people out of public baths. According to the French physician Ambroise Paré, hot water was considered harmful as it destroyed the skin’s protective oils, which then allowed “pestiferous vapours” to seep into “the little air holes in the skin.”

*

The water in the YMCA hot tub looked yellowish one night, the grout grimy. When I lowered myself in, I thought, it’s not hot enough. Two days later, my right breast swelled painfully. The doctor said it might be mastitis, a staph infection common in lactating women, but since I was not lactating he mentioned that it could be inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). I left his office feeling relatively calm, thinking, well, that’s probably not it and even if it is, it’s probably in the early stages. I was uncharacteristically sanguine on the drive home, but—Google me this!—inflammatory breast cancer is the most aggressive type, with a dismal ten percent survival rate. I freaked out, especially after I read that mastitis was extremely rare in women over 50.

The doctor said the antibiotics would reduce the swelling in 48 hours. Or not. If this was IBC, the inflammation was caused by tumors blocking the milk ducts, so there would be no reduction in swelling. With a Sharpie, I outlined the red area on my chest to monitor shrinkage. And then I prepared for the worst. I told myself that 50 years was a good long life, that many people, like Steve, had far less time, that if anyone in my family should die young it should be me since I have no children, that my modest assets could contribute to my nieces’ and nephews’ college costs.

After 24 hours, the redness seemed to recede. I spent another day with anxiety like an electric current coursing through my body, but after 48 hours the swelling had diminished. “How did I get a staph infection in my breast?” I asked at the follow-up appointment. “It probably entered through a tiny cut,” the doctor said. On my breast? I developed a theory. Maybe there was a small cut in my underarm from shaving, and when I sank to my neck in that nasty tepid hot tub water—just warm enough to breed bacteria—the microbe swam into a “little airhole” in my skin.

My theory was not far-fetched. A Chicago man sued his fitness club after he contracted a staph infection—folliculitis MRSA pseudomonas staph—from using their hot tub. He lost his case because he could not directly link bacteria in the water to his infection, even though evidence abounds that poorly maintained hot tubs breed dangerous bacteria. In 2006, Texas A&M researchers tested water from 43 private and public hot tubs and found bacteria from feces in 95 percent of the samples and the staphylococcus bacteria in 34 percent. A teaspoon of tap water, they found, contained about 138 bacteria, while a teaspoon of hot tub water averaged 2.17 million.

The most common illness-causing bug in hot tubs is Mycobacteria avium, which thrive in the slime inside wet pipes. When you turn on the jets, the water is aerosolized and you can inhale mycobacteria, which causes a bronchitis-like infection called “hot tub lung.” In 2008, a 41-year-old Australian man with hot tub lung required a double-lung transplant. You can also inhale the legionella bacterium in a hot tub, which causes Legionnaires’ disease, named for a bacteria that sickened 221 men—killing 34 of them—after an American Legion conference at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in July 1976. It took 20 epidemiologists from the Center for Disease Control six months to identify the bacterium, which had spread through the hotel’s air conditioning system, which means you don’t have to get wet to get sick. Three elderly men in England died from Legionnaires after walking by an unclean hot tub and breathing the steam. The tub—the Nordic Impulse Deep Hot Tub—was on display at a JTF Mega Discount Warehouse.

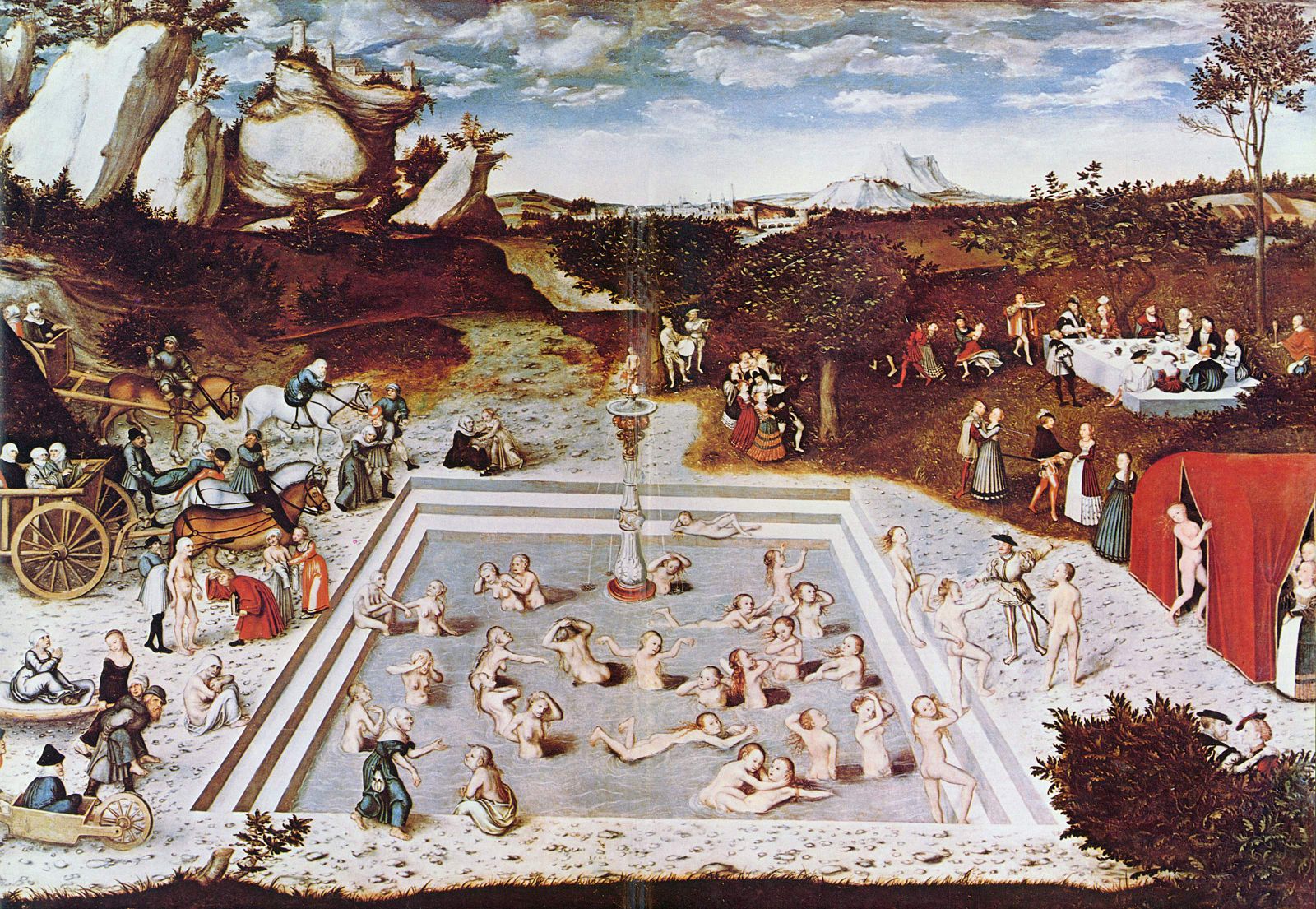

The Fountain of Youth, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1546

The Fountain of Youth, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1546

After the Dark Ages began to lighten, Europeans rediscovered the pleasure of baths. “I have seen in my travels almost all the famous baths of Christendom,” Montaigne wrote in the late 1500s. Bathing was “generally wholesome,” he concluded, certainly better than having one’s “limbs crusted” and “pores stopped with dirt.” Society had suffered, Montaigne wrote, “by having left off the custom . . . of bathing every day.” An 18th-century physician in Briton claimed that the thermal waters at Bath could heal everything from “the longing of maids to eat chalk, coal, and the like” to “hypochondriacal flatulence.” Even religious leaders promoted bathing. In 1747, John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, wrote that baths cured more than 50 illnesses, including breast tumors, fits and convulsions, wandering pains, the falling sickness, leprosy, and the bite of a mad dog. “Cleanliness is next to Godliness,” Wesley said, along with his less-quoted advice: “Do not stink above ground.”

In pre-Revolutionary America, among aristocrats with money to travel there was a “craze” of taking the waters. In 1761, George Washington sought relief from rheumatic fever at the Berkeley Warm Springs in West Virginia. “We found of both sexes about 200 people at this place, full of all manner of diseases and complaints,” he wrote. In 1771, John Adams traveled to Stafford, Connecticut, in hopes that the waters would ease his nerves. “The water is very clear, limpid, and transparent,” he noted.

But at the same time, like Christians in Medieval Europe, religious leaders in the colonies condemned bathing. Protestant ministers in Pennsylvania petitioned the governor to halt the development of public baths, fearful that they inspired an “immoderate and growing Fondness for Pleasure.” In Colonial America bathing for personal hygiene was considered “impure” and the practice regulated. In Boston, it was illegal to take more than two baths a month. In Colorado you needed a doctor’s prescription, and in Philadelphia and Wyoming, anyone who took more than one bath per month could be jailed. Even a century later religious leaders fretted. Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science, warned that, “Washing should be only to keep the body clean, and this can be done with less than daily scrubbing.” Anti-bathing sentiment was so widespread that an 1891 editorial in Science argued for “the habit of daily bathing,” which, the author lamented, had been “seriously questioned.”

*

One night there was a biohazard in the pool—some kid pooped in the water—so I couldn’t swim laps. Instead I sat in the hot tub. In came the fat man, or the waning man, I should call him. We were the only two in the tub and I spoke to him for the first time in the years I’d seen him. “My Russian friend is in Florida taking classes,” he said. “She loves the heat there.” I wondered why he called her “friend” and not “ fiancée.” I usually avoid contact with people when I’m feeling blue, as I was that night, so I was surprised to find myself talking to him. At first we’d hesitated, a reserved hot-tub politeness, which made me think he was more considerate than I’d thought. In Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventures of the Illustrious Client,” Dr. Watson observed that Sherlock Holmes was “less reticent and more human” in the Turkish baths “than anywhere else.” Nearly naked in close proximity to other humans, floating in placental-like warm water, I was forced to confront raw humanness, his and my own, my façade of imperviousness weakened.

In hot tubs, strangers have confided in me. One morning at the YWCA hot tub in Lansing, Michigan, where I lived for six years after Steve died, a man I’d never seen before asked me if I listened to “that new jazz station.” I shook my head. “I’m tired of listening to country,” he said. “All they ever do is cry about a broken heart.”

I nodded.

“My wife left me two weeks ago after 18 years. She was 20 years younger than me.”

He asked me how old he looked. I thought he looked 60, so I said, “55?”

He smiled proudly. “61”

He shook my hand and said, “Nice talking to you,” then stepped out of the tub and I never saw him again.

Montaigne wrote of public baths, “He who does not bring along with him so much cheerfulness as to enjoy the pleasure of the company he will there meet will doubtless lose the best and surest part of their effect.” At the Y in Maine recently, I overheard a man say he was hit by a school bus, and that he wished he had a hot tub in his backyard so he could sit in the tub under the stars. “Mother Nature, I think she’s doing a pretty good job,” he said. When the woman with whom he’d been talking left, he floated over next to me and picked up his conversation where he left off. It didn’t matter to whom he talked; he just needed to tell his story.

*

In the mid-19th and early 20th centuries in the US, bath nay-saying gave way to its opposite—zealous advocacy. The impetus was to cleanse the stinking immigrants flooding into east coast cities—Boston, New York, Philadelphia. The millions of Irish fleeing famine, and Italians, like my grandmother, who lived in Brooklyn’s tenements—were “too rank and malodorous for the nostrils of the refined,” a letter-writer complained in the New York Times. In New York City at the turn of the 20th century, 97 percent of tenement residents had no access to bathrooms. Wealthy and middle-class reformers rallied for the construction of public bathhouses to prevent contagions—cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis. New York City had a higher death rate in the 1880s than Paris, London, or any major US city.

“There is enough chlorine in this water to kill any bacteria, I’ve assured myself time and again, but to my dismay I discovered that chlorine actually loses its disinfecting power in warm water, while bacteria thrive.”

In 1890, Cosmopolitan Magazine held a contest to design New York City’s first public bathhouse. The winning entry resembled a luxurious Roman bathhouse, with a façade of pillars and arches, and inside, “plunge pools, Turkish baths, and steam rooms.” The actual facility, though, was utilitarian, with dozens of “rain baths” to efficiently clean as many people as possible. At the World Hygiene Congress in Berlin, the “rain bath” had just debuted, a radical shift from tubs to “upright” bathing, introduced by Dr. Oscar Lasser as the Volksbad, or the “people’s bath.” The People’s Bath of New York opened in 1891 in the Bowery neighborhood, with Wesley’s aphorism—“Cleanliness is next to godliness”—engraved above its entrance. Each bather received a ticket for an allotted 20-minute shower. To assure an orderly operation, the waiting area was supervised, sometimes by police.