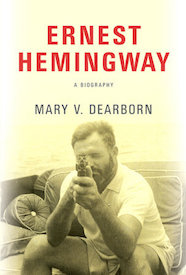

The Superhuman Charm of Ernest Hemingway, the “Most Shot-Up Man in America”

On the Original Charmer of the Lost Generation

Ernest Heminway returned home to Oak Park, Illinois, in 1919, following his wounding in Italy with the Red Cross ambulance service in Italy in the first world war.

The word “charisma,” overused today, originally had, and in some organized religions still has, a specific theological meaning: from the Greek, it means, roughly, “the gift of grace” or “a favor given.” Max Weber first used the word to describe human relationships. “Charisma” has been widely used in its modern sense only since the 1950s, long after Ernest Hemingway’s youth and young manhood, when he had it in abundance. The term retains several connotations: it refers to something either given if not by divine forces then by the supernatural; it is not available to everyone and cannot be sought or acquired; it has something to do with leadership; and it is always a positive term, carrying meanings of kindness, attractiveness, and self assurance.

The word describes the young Ernest. And Ernest got his charisma, without question, from his mother. Like her, he had a commanding presence. As a young man, Ernest was “splendidly built,” “robust, hulking, vivid”; as he aged he would become massive. He inherited his build from Grace: she was heavy-boned and strong and grew to have a massive bosom and upper arms, though her waist remained well proportioned. Her daughter Sunny stated, “When she entered a room everyone took note of her.” Described as a “large, handsome woman,” Grace was “formidable, statuesque.” She was “unforgettable,” according to one biographer.

But Grace apparently was commanding in ways that went far beyond her size or looks. Always curious about new experiences, as a young woman she had heard bicycling was “really just like flying,” so she donned bloomers and tried riding her brother’s new bicycle (“Of course such a costume is not graceful,” she told Clarence, then courting her, “but it is sensible”). She seems to have had boundless energy and enthusiasm, whether for creating her children’s baby books or pursuing her music. She collected royalties from several songs she composed (including “Lovely Walloona”). Later in life, when her voice had deteriorated to the extent that she could no longer give lessons, she took up art and taught that instead, as well as enjoying brisk sales of her paintings. (She would repeatedly ask her son to submit them to the Salon Show in Paris.) She designed and built furniture. Later still, she had a lucrative career lecturing on such topics as Boccaccio, Aristophanes, Dante, and Euripides, and wrote poetry as well. Though there’s no other evidence for this activity, which would have entailed an entirely new and difficult skill and finding access to some formidable equipment, she wrote Ernest in the late 1930s asking how he liked the tapestry she had woven for him. The vast amount of material relating to Grace’s life in the primary repository of her papers, at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, attests to this energy, and the scores of admiring letters from neighbors and other community members, from appreciative students and their mothers, speak to her charm and the contagious nature of her sheer zest for living.

Though Ernest never took up so dizzying a range of pursuits, not least because of his lifelong focus on writing, it is instructive in this light to consider his other activities in later years, from hunting and trout fishing on Western dude ranches, running with the bulls in Pamplona, covering two wars, fishing the Gulf Stream, and going on safari—twice—in Africa. His enthusiasm for these endeavors was, by all accounts and measures, so extreme as to be genuinely infectious. The number of friends and acquaintances he converted to deep sea fishing alone was considerable. More than this, however, was the appetite for experience that he inherited from his mother, never more apparent than in his youth. Add to this the undeniable fact that—his claims about his upbringing aside—he grew up in a loving family with adoring parents and siblings, encouraged to believe that he could do almost anything he set his mind to, given his intelligence, talent, and physical presence, and it is no wonder that Ernest Hemingway in his adolescence and early adulthood seemed to all he met a young man of immense charm and potential. He virtually commanded affection, admiration, and attention. A natural leader, he was the center of attention in any group, just as he had been when he “held court” in the Milan Red Cross hospital in 1918. The poet Archibald MacLeish would later say that Ernest was the only other man he knew besides FDR who “could exhaust the oxygen in the room just by walking into it.”

If “charisma” carries a positive connotation, it also conveys the sense of power—power that the bearer can wield ruthlessly, to get his or her way, to dominate or intimidate. Grace was fully capable of this, and Ernest no doubt learned about this aspect of charisma from her. After the war, whether because of clinical shell shock or simply a considerable upheaval in his philosophical and psychological makeup and in his worldview, Ernest returned to Oak Park a changed person. It was not in his nature to simply come home and get on with the business of living, as another returning soldier might. Rather, Ernest spent several months enjoying the status of the conquering hero. If there is such a thing as a professional soldier, Ernest was a professional veteran. Even literally so, as he enjoyed a modest success lecturing on the war in the Chicago area, to the point that he had business cards made up advertising his skill. There was nothing cynical about this; Ernest was bursting with what he had seen, heard, and felt, eager to talk about it and share his enthusiasm. We might today say he was still high on his Italian experiences in love and war.

He was ready as soon as he hit American soil. Disembarking from the Giuseppe Verdi on January 21, 1919, he gave an interview to a reporter from the New York Sun who singled out from the other passengers the striking young man in cordovan boots and a cape lined in red satin over his officer’s tunic. In a wildly error-ridden article titled “Has 227 Wounds, But Is Looking for Job/Kansas City Boy First to Return from the Italian Front,” the reporter noted that the soldier had 32 pieces of shrapnel removed in Milan but had enough operations ahead of him to last “a year or more,” that he probably had “more scars than any other man in or out of uniform,” and that he had, after his recuperation, returned to the front until the armistice. In a burst of enthusiasm, Ernest told the journalist that he was looking for “a job on any New York newspaper that wants a man who is not afraid of work and wounds.” The Chicago Tribune picked up the story and welcomed him back with the headline, “Worst Shot-up Man in U.S. on Way Home.”

__________________________________

From Hemingway: A Biography by Mary V. Dearborn, courtesy Knopf. Copyright Mary V. Dearborn, 2017.

Mary V. Dearborn

Mary V. Dearborn received a doctorate in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University, where she was a Mellon Fellow in the Humanities.