The Story We Don't Talk About:

On Irishness, Immigration, and Race

"Being White Can Make a Whole Community Forget Who They Are and Where They Came From"

In January of 2014, a girl who had left from Cobh in Ireland (formerly known as Queenstown) journeyed across the Atlantic, and skipped rosy-cheeked off an airplane at John F. Kennedy Airport to start her new life. That was me, compensating for my indoor ghost face with too much blush in a shade aspirationally entitled “orgasm.” In January of 1892, a girl who had left from Queenstown (now known as Cobh) skipped rosy-cheeked off a boat at Ellis Island to start her new life. That was Annie Moore, flushed with embarrassment at the unexpected fuss being made over her by the officials on the island. She was the first immigrant through the new processing center that opened its doors on January 1 of that year.

I know she was rosy-cheeked, because The New York Times said so, back in the day. I’m only guessing as to the reason. Maybe she wasn’t mortified by the attention and the redness was simply caused by the icy wind whipping through the harbor. Maybe she just lit up with the anticipation of seeing her parents for the first time in years and the relief of no longer being her little brothers’ sole guardian, as she had been on their voyage. I have no idea. I grew up knowing all about the people who left my hometown, but nothing about what happened next. I come from Cobh, an island in the mouth of Cork Harbor, the departure point for more than two million Irish people between 1845 and 1945, the last place Titanic stopped before it—well, I don’t want to ruin the movie. While other children went to amusement parks, our school trips were to replicas of coffin ships, so named because of the high death rate as they transported people to America during the Irish famine. My classmates and I filed into the wooden bowels of a ship to listen to audio of people groaning, and look at wax figures leaning over buckets. So, you see, this whole leaving thing, it’s in me.

I first came to America on a P-3 visa, an “Artist or Entertainer Coming to Be Part of a Culturally Unique Program.” The Culturally Unique Program I was invited to was the Kansas City Irish Fest. Kansas City is exactly bang in the middle of America and it’s not even in Kansas, it’s in Missouri. That’s one of my go-to facts to tell guys I’m trying to impress. It never works. Often, they already know. More often, they don’t find it interesting and are confused as to why I told them.

“I come from Cobh, an island in the mouth of Cork Harbor, the departure point for more than two million Irish people between 1845 and 1945.”

The festival was a mishmash of Americana and Irishness and Irish-Americanness. With signs on the walls stating guns were not allowed inside the festival grounds, haggis from Scotland for sale at the food trucks, and Appalachian bands fiddling wildly on the big stage, I couldn’t fully get a grip on where I fit in. I woke up, jet-lagged, to a thunderous sound coming from the hotel corridors. Unclear about what I was hearing, I blearily poked my head out and watched, amazed, as young American girls in elaborate dresses and huge wigs pounded the carpet in socked feet, practicing for their Irish dance performances later in the day.

The sun beat down outside, and the water in the fountains in the square was dyed green. You know, like the green water that runs throughout Ireland. Extraordinarily friendly residents, volunteering their time at this huge event, told me about their visits back to Ireland, and explained how Irish they were, and how important this festival was to them and their children. These children, red-haired and grinning, were also Irish? Yes, just one more generation removed, making it five generations ago that the family moved there from Leitrim, a stony little county in the Irish midwest with a population that is currently less than a fifth of what it was before the famine, a place that, today, has more sheep than people.

Annie Moore was on my mind during my first few days in the U.S. Her story was told to me by the genealogist Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak. The reason she has two last names is that she took her husband’s name. He too was a Smolenyak, but no relation. Anyway, Megan had figured out a key mystery in the Annie Moore story. For almost 50 years, another Annie Moore was thought to be our girl Annie, the first immigrant through Ellis Island. This other Annie Moore had actually been born in Indiana, and moved to Texas, where she married a man descended from the Irish patriot/heartthrob Daniel O’Connell, the man who had spearheaded Catholic emancipation back in colonized Ireland and was very handsome, in a James Gandolfini kind of way.

That Annie Moore and her star-dusted husband owned a hotel in New Mexico and all was well, until he died and a few years later, on a trip back to Texas, Annie was hit by a streetcar and died too. It was that Annie Moore’s story that caught on, probably because it’s such a classic American tale, full of dreams and going west and social mobility. She was held up as a brave little immigrant, who worked hard, snatched herself a good life, and died in an appropriately dramatic fashion. Her descendants were honored in a ceremony at Ellis Island before Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak discovered that she was, in fact, the wrong Annie.

“I didn’t know what they thought they were missing. In America, they had Michael Jackson and pizza and money, so much money!”

The right Annie, the 17-year-old who left from Cobh, never went west. She lived her whole life in America just a couple of miles away from Ellis Island, on the Lower East Side. The tenement home she arrived to on her first trip, her entire family sharing a couple of rooms in a noisy, overcrowded building, was the complete opposite of what I experienced, alone in my oversized hotel bed ordering room service, with plump white pillows and soft woolen blankets to cozy up in as the air-conditioning chilled the huge room around me.

In Kansas City, surrounded by Irish-Americans, I felt like I had met them before, but where? Because of my hometown’s history of emigration, every summer the promenade and cafés would fill up with American tourists, arriving by liner into the harbor or by the busload from Cork city. They were usually elderly, and as children we regarded them with a fond sort of mockery. Occasionally they would ask for photos with us, particularly of my freckled friends. They bought soda bread and Aran sweaters, anything that was for sale, really. We joked that you could sell them stones, if you convinced them that the stones were Irish enough. Some American tourists would break away from their guided tours and go driving around the island. They sometimes came knocking on our door, asking to look inside the house, thinking it was a replica of where their ancestors may have lived. Perhaps they were right: we lived in a pretty, old farmhouse, with a half door wreathed in honeysuckle, that would have looked the same one hundred years before. My mother was polite to them, but didn’t usually let them in, saying to us at dinner that “those poor Yanks were demented.”

The thought that, generations later, their descendants might return to the harbor town they had departed from would surely have amazed Annie and the millions who left with her. People only ever left, and perhaps it was a shadow of that amazement that darkened our feelings toward these perfectly lovely Americans. As a child I certainly couldn’t fathom why they would bother to visit a boring seaside town in a tiny nation, sitting on hot buses for hours as they wound their way around the countryside, taking photos of some plain old fields full of cows. America was so cool! Their ancestors had left Ireland for a reason, and now they were reaping the rewards. I didn’t know what they thought they were missing. In America, they had Michael Jackson and pizza and money, so much money! Not like Ireland, where the only music we made sounded like sad mermaids singing and I had to share a pork chop with my sister and nobody had any money.

As an adult, when I witnessed this little city in the middle of America drop everything for two days and piece together a version of an Ireland that doesn’t exist anymore, I suddenly understood the impulse. I felt sorry then for not being kinder to the visiting Americans, for sighing on the inside when someone told me in a loud American accent they were Irish too. In Kansas City, I began to empathize with those “poor demented Yanks” a lot more. Whoever it was of theirs that left Ireland all those years ago took with them a snapshot of the country, its people, and its culture. The details on that picture faded throughout the years, and it could never update itself to show the changes in the country it portrayed. That picture’s opaque story was all they had to go on, except perhaps some Aran sweaters and soda bread handed to them by bemused Irish people a century on down the road.

The place where their ancestors landed was at best a blank slate; at worst, an active genocide site. In their new country, America, they did not have a culture stretching back hundreds of years. There was no set of memories to explain who they were and how they got to be that way; no music, no stories, no jokes, except those that came with them across the Atlantic. Of course they clung to the trappings of a culture they’d left behind, and who am I to begrudge them a bit of corned beef, a stick of salty Irish butter? That’s probably just the kind of thing Annie would have felt homesick for. Family lore says her coffin was too wide to fit down the narrow stairs of her tenement house, and had to be hoisted out the window.

It’s easy not to think about these questions of Irishness and Irish-Americanness, until something big comes along that forces you to. The first year I lived here, I covered the Saint Patrick’s Day parade for The Irish Times. Not the big parade, not the one where thousands march and millions watch, the biggest annual parade in the city and the only one that uniformed firefighters and police are allowed to participate in. Not the one that banned gay people from marching under their own banner up until 2015. Not the Fifth Avenue parade, the one that shuts midtown down and marches past visiting dignitaries who sit in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, led by ranks of white men in black suits and sashes.

Instead I went to Queens, to see about their Saint Patrick’s Day parade. A couple of weeks before the event I went to see how preparations were going, and found myself in a small kitchen two blocks away from the last stop on the Q train—it smelled like caramel and clean laundry. I sat chatting with the owner, Tom Moulton, a full-time pediatric hematologist oncologist and part-time baker. He was making soda bread, scones, ginger snaps, and oatmeal cookies. That old soda bread again, I thought, what would we do without it? Everything he made was for a bake sale to raise funds for St. Pat’s for All—a parade founded by Tom’s husband, Brendan Fay, then in its 15th year. The title explains it: it’s a parade for everyone, for anyone who wants to join in.

“It’s easy not to think about these questions of Irishness and Irish-Americanness, until something big comes along that forces you to.”

Every Saturday morning in the months leading up to the parade, Fay and his committee meet in Molly Blooms, an Irish bar in Sunnyside, to organize portable toilets and pipe bands. They even send a truck to Brooklyn to collect puppets from a warehouse there. The puppets are free to use because they have been retired or rejected by theaters, so the committee takes them and distributes them to neighborhood kids who’ve come along to watch the parade and suddenly find themselves a part of it. I mean, rescue puppets? It’s almost too adorable to be true.

It is true, and there are more than 2,000 witnesses each year, the people lining the route from Sunnyside to Woodside. St. Pat’s for All was founded many acrimonious years after the 1992 ban on gay people marching under a banner at the Fifth Avenue parade. This ban seemed off to me, for many reasons. The first is the fact that parades are the gayest way to travel and should therefore never exclude gay people. And also, it showed how out of step the Irish-Americans behind the parade were with the country they claimed to represent. While they clung to their “traditional values” and fought to exclude gay people from their parade right up through the courts, Ireland itself moved on. In 2015, Ireland voted by a huge majority to legalize same-sex marriage, becoming the first country in the world to do so by popular vote. The big parade, the one that goes up Fifth Avenue, seems solemn and self-important and symbolizes to me the difference between the idea of Irishness and the reality of Irishness. We’re straight, we’re white, and the men know best! versus We’re all different and that’s fine, but we agree on one thing—we’re not English.

Last Thanksgiving, I went for a wander around Annie’s old neighborhood, and peeked into St. Mary’s Church on Grand Street, the one that had been rebuilt after it had been burned down by anti-Catholic nativists in the 1830s. It was self-defense against this kind of violence and bigotry that led to the Ancient Order of Hibernians forming in the first place, and so I see that it started off out of necessity, and with valor. I had this romantic idea that when the Irish first started coming in droves to America, fleeing oppression and famine, they would surely feel an affinity with the people being oppressed in their new country. That’s not the way it panned out. By the time Annie arrived, the Irish had a much surer footing in the city’s political and social life than the generations before her. They were clannish, looking out for their own; perhaps they had to be.

I have mixed feelings about this. I’m glad that they made it, but sorry they often stood on the backs of other marginalized communities to do so. Annie and her family did not have an easy life here, living as they did in the tenements. But at least they had a network, hard won by the immigrants who came before them, people who looked out for each other and made their new life a little easier. The favor of hospitality extended to her is not extended to everyone, even today. It’s troubling to see how privilege accumulates over generations, particularly white privilege in the U.S., and, when people reach a certain level of safety, to see how they pull the ladder up after themselves.

The difference between the Irish in Ireland and the Irish in America has always existed. I love reading accounts of the time the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass visited Ireland in 1845. He spent four months traveling around the country and was a huge hit, appearing to a crowd of over 1,000 people in Dublin one day alongside the aforementioned emancipator/dreamboat Daniel O’Connell. The men were kindred spirits with a lot in common: both determined to resist their oppressors, both renowned orators, and both leaders in the worldwide fight for social justice.

O’Connell went as far as calling Douglass “the Black O’Connell,” a nickname that must invoke a healthy dose of side-eye in us all. First of all, Irish Catholics suffered hugely under the English, but their situation was not on par with slavery. In a fascinating paper by Lee Jenkins titled “Beyond the Pale: Frederick Douglass in Cork” published in The Irish Review, the writer notes the following. “The Belfast Banner of Ulster, 9 December 1845, reports Douglass’s feeling that Irish people did not always ‘sufficiently distinguish between certain forms of oppression and slavery.” The Cork Examiner reports Douglass’s insistence that “I stand before you . . . a slave. A slave not in the ordinary sense of the term, but in its real and intrinsic meaning.'” That truth, and the clarity with which it was spoken, are important to hold onto today too, as the American alt-right continues to cultivate the lie of white slavery.

Secondly, on the whole “Douglass is the Black O’Connell” thing, imagine deciding that someone is so wonderful that you simply must bestow upon them your highest honor: reducing them to one facet of their identity and comparing them to yourself. Try it! I did, and Jake Gyllenhaal, aka “the Male Higgins,” was thrilled and flattered.

But back to what would become the biggest annual event in Irish America’s calendar. When the very first Saint Patrick’s Day parade happened in 1762, I was but four years old. It sounds like it was a fun event. There were just a few Irish soldiers serving in the British army, and they realized that here in America they were permitted to wear green, and sing songs in Irish, and generally have a good time doing stuff they weren’t allowed to do back home, so they paraded around for a while, playing the pipes. In later years, the aforementioned Ancient Order of Hibernians took over the running, and to this day they lead the parade, albeit now under a different name. Those were the people I tried to talk to, and that’s how I discovered that trying to talk to an ancient order of anything is tough. Reaching the Fifth Avenue parade committee was tricky, but someone finally answered the phone. They were having a function to honor their grand marshal, so I phoned their office to ask if I could go along to write about it. A voice replied, “Absolutely not.”

Having been shut down by the big parade, I took comfort in an invitation to the St. Pat’s for All celebration of their two grand marshals. It was hosted at home by the Irish consul general and a chubby black Labrador whose name I didn’t catch. One of that year’s grand marshals, Tom Duane, looked like a clean-shaven Santa, and chuckled like him too. He was elected to the state senate in 1998 and became the senate’s first openly gay and first openly HIV-positive member. Proud of his heritage—all four grandparents were Irish immigrants to America—Duane was arrested many times for protesting at the Fifth Avenue parade. He was among the first politicians to support Fay’s parade. It was fun to meet him at a time when the tide was turning firmly in his favor. “Now they’re all at it!” he said, a grin ruining the credibility of his attempted eye-roll.

The other grand marshal was Terry McGovern, a softly spoken human rights lawyer with copper-colored hair. In a short speech she honored her mother, who was killed at the World Trade Center on September 11, saying that her mother was the first person to introduce her to the concept of human rights. Then a man pulled out his violin; he looked like an extra from The Sopranos, but he played like an angel, specifically an angel from Sligo. He closed his eyes as the notes of the reel whirled and slipped through the assembled crowd and we whooped and tapped, the city glittering beneath us.

This right here was a version of an Irish America I felt at home in. Annie Moore had married a German man, and, while she stayed close to her family throughout her life, she lived in one of the most multiethnic neighborhoods in the country. I wondered how she defined her identity, if she ever had time to consider it. Annie certainly never had the option to return to Ireland, so, like many an immigrant to this day, she had to figure out ways to make the U.S. feel like home.

I’m very lucky to get that chance to feel at home here, and even luckier to go back and forth freely between the two countries. For most people around the world, America is a fortress. Forget about moving here; for huge swaths of the global population it is impossible even to visit. Visas to the U.S. are, as a gym instructor once said when I tried to do a burpee, “extremely challenging and likely not possible.” I’m not even on an immigrant visa: I’m on a non-immigrant visa, which is still very difficult to get. Before my P-3 visa expired I applied for an O-1 visa, which is, by design, only available to the privileged few. To secure it you have to already be a celebrated individual, or at least have the means to make it seem that way.

There’s an O-1A, for individuals with an extraordinary ability in the sciences, education, business, or athletics. Nobel Prize winners, Olympians, Fields medalists—these are the ones who come through on the O-1A. The O-1B is for individuals with an extraordinary ability in the arts or extraordinary achievement in the motion picture or television industry; and that’s me! Having been on a TV prank show in Ireland and winning an award for it, I can honestly claim that I have an extraordinary ability in the arts. That wasn’t the only thing I needed. As part of my application, I also had to collect testimonials from recognized experts in my field. Testimonials are garnered by asking people to vouch for you, in writing, to the Department of Homeland Security. Not just anybody; they must be supremely successful and way above you on the show business scale of one (me) to a thousand (Diana Ross).

These testimonials are known as “the Twelve Letters,” and gathering them is a mortifying process for anyone remotely insecure about their worth as a person and an artist. You may run into some psychic trouble if you are, say, a woman, or an Irish person, or a person who was raised Catholic. Immigration lawyers come up with sample letters, and these letters are brimful of hyperbole. They have to be, to convince the officer in charge of your case that you are indeed an alien of extraordinary ability. Words like “magnificent,” “peerless,” and “transcendent” are encouraged. My advice to anyone collecting these is to consider taking regular doses of cocaine throughout the process; this will give you the false confidence necessary. If you’re not comfortable with that, you will need at least a shot of testosterone in the mornings for the two to three weeks it takes to finish the application.

“I’m very lucky to get that chance to feel at home here, and even luckier to go back and forth freely between the two countries. For most people around the world, America is a fortress.”

My extraordinary ability is doing stand-up comedy, carrying out prizewinning pranks, and persuading friends who do voice-overs in cartoons to write letters to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, telling them what an absolute legend I am. There are scientists in India and filmmakers in Colombia and orphans in Jordanian refugee camps, all trying to get to America, and I’m on my second O-1B visa, which will last me for three more years, after which I can apply for an extension. The question “Why me, and why not them?” has no satisfactory answer.

Annie Moore, that first immigrant through the gates of Ellis Island, never had any papers. She did not have a passport or a visa, and white immigrants did not need them back then. Chinese people were not so fortunate, having largely been banned from immigrating to America ten years earlier. Annie was an undocumented, unaccompanied minor, and she sailed right in. She was greeted with fanfare by the U.S. authorities, who gave her a gold coin to commemorate the occasion, then she was allowed to go and meet her parents, wholeheartedly encouraged to establish herself as a new American.

I think about Annie and me, both of us existing in the exact right set of circumstances to allow our lives in America to happen. We arrived at just the right time with the right qualifications. In her case she was young and healthy and white. Same here, with the addition of a favored career and good connections. I think about the people who were simply born in America, who just arrived on this planet in this coveted little corner, who have never had to consider leaving. I think too about the people who die trying to get here, like my producer Erika’s uncle, who suffocated in a container on a ship when he was just 20 years old, the eldest son of 18 children, the one who was supposed to send for the others in Colombia once he’d made a life for himself here. And I can’t fathom what it must be like for the people who have lived here since childhood, who are American in every way save their papers, but have no claim on the place, no path to citizenship. I mean, the sheer dumb luck involved in it all!

There’s a heartbreaking part of his autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom where Douglass recounts his time in Ireland and writes about being treated with dignity, treated just like anyone else, really, and what that meant to him as a former enslaved person. “Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe, and lo! The chattel becomes a man.” And yet, back home in the U.S., many, though not all, Irish-Americans and their leaders opposed Douglass’s fight to end slavery and gain rights for African-Americans.

A book called How the Irish Became White is a tough read for those of us harboring any illusions that the Irish struggle for autonomy may have translated to support for black America’s struggle for justice. It chronicles the earliest days of Irish immigration, when the newly arrived Irish were in the same social and economic class as the free black Americans of the North. They already competed for jobs, and an end to slavery would heighten that competition. Like most immigrants, the Irish wanted to assimilate as quickly as possible, and soon realized that they had what we now know as white privilege, like in the labor movement where they rose to power, a movement African-Americans were excluded from. It’s a tragic and all-too-human story of how one group of oppressed people learned to collaborate in the oppression of another in order to get ahead themselves.

It’s also a story rarely told, at least among ourselves.

I’ve certainly heard a lot more about how hard the Irish had it, about our particular struggle, than about how, despite our own experience and despite consistent pleas from people like Daniel O’Connell back home to support the abolitionists, the Irish largely chose to identify simply as white, not Irish, not immigrant, in this new society where race meant everything. And the Irish definitely did have it rough, fleeing civil unrest and religious persecution, arriving to a new country that was often hostile to them because of their nationality. On Saint Patrick’s Day of 2017, with a White House full of Irish-Americans, that was the narrative on blast. Vice President Mike Pence spoke about his hardworking grandfather who left the Irish midlands to make a better life for his family in Chicago in the 1920s, attributing his family’s success to grit and spirit, failing to mention that the Irish were always in a better position in America than enslaved Africans and their descendants, freed or not, omitting the part where the Irish at that time leveraged their whiteness to ensure they were better off than Native Americans, and nonwhite immigrants too.

Being white in America is so potent, so seductive, it can blind a person without them knowing it. Being white can make a whole community forget who they are and where they came from. The year Frederick Douglass visited Ireland was the year the country began its terrible spiral into a famine that ultimately killed a million people. There had been food shortages before, and the extent of the disaster was not yet clear, but he writes in a letter of the horror of leaving his house and being confronted with the sight of hungry children begging on the street.

It’s painful to look through that lens at the present and see so many powerful Irish-Americans, like Paul Ryan, whose great-great-grandfather survived the famine and fled to America in 1851, doing everything they can to stop today’s refugees from entering the very country that gave their family sanctuary when they most needed it. That same Saint Patrick’s week that saw a celebration of Irishness in the White House also saw a potato head by the name of Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s budget director, with grandparents from Mayo, busily announcing cuts to international famine relief with a shamrock pinned to his suit, unaware of, or perhaps unconcerned with, just how grotesque that was.

“The Irish at that time leveraged their whiteness to ensure they were better off than Native Americans, and nonwhite immigrants too.”

What else has happened in the 125 years since Annie Moore arrived? Well, the ban on Chinese immigrants has been lifted, and the ban on Muslim immigrants threatened and attempted, with some measure of “success.” Catholic churches are no longer being set alight by nativists, but synagogues and mosques are being vandalized by people on the same tip. In 2012 a Sikh temple in Wisconsin was targeted by a white supremacist who killed six people and wounded four. Nazis are on the streets and hate crimes are on the rise. A man whose own immigrant mother walked through the same Ellis Island doors as Annie campaigned for the presidency by slamming immigrants at every turn, and won. We’re hearing echoes so loud they’ve become the sound of today.

Echoes, of course, are still sounds in their own right. Those sounds never went away for some of us, for black people whose churches have been targeted with sickening consistency from the Civil Rights era right through to today. In 1963, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Alabama, killing four little girls and injuring 22 other people. In 2015, a white supremacist named Dylann Roof hoped to start a “race war” by murdering nine black people in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, a 200-year-old church that played an important role in the history of South Carolina throughout slavery, the Civil Rights movement, and the more recent Black Lives Matter movement. I used to think that the early days of immigration to the U.S. happened during a “different time,” but hatred unchecked has a way of collapsing time, trapping us all until we deal with it.

I still go home for the holidays. I call Ireland home, but America is my home too. In 2016 I stood on the darkening quayside in Cobh on Christmas Eve, and looked at a statue of Annie there. She is small and capable, her hands lightly resting on her little brothers’ shoulders, her eyes gazing back at a country she would never see again. An Irish naval ship had returned to the harbor earlier that week from its mission off the coast of Libya, a mission that rescued fifteen thousand people from the Mediterranean Sea in 2016, though that year was still the deadliest for migrants since World War II, with more than five thousand people drowning as they tried to find safety, or a better life.

On my flight home to New York after Christmas, I imagined meeting Annie today. I’d make a pot of tea and tell her how her family turned out so far. She never made it out of the city, but Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak tracked down her descendants. They are spread across the country: actors and doctors and financial consultants and stay-at-home parents, with Jewish and Latin and Asian blood mixed in with her own. Then I’d explain to her loudly and slowly how to follow me on Instagram, and maybe take a few selfies with that funny koala filter.

Annie Moore never made a fortune, or wrote a book, or invented a computer, and why should she? Why should immigrants be deemed extraordinary in order to deserve a place at the table? She did enough. She was just one woman who lived a short life, a hard one. She had 11 children, but only six made it through to adulthood. Can you even imagine burying five of your children? I can’t. I tuck that part away in the “she must have been different from me, with fewer feelings” folder, the delusional one that’s full of news stories from faraway places that are too terrible to bear. Annie died before she turned 50, but she lives on in every girl from a country shot through with rebellion and hunger, and in every immigrant who gives America their humanity, as every immigrant does.

A portion of this essay originally appeared in the January 1, 2017 issue of the New York Times.

__________________________________

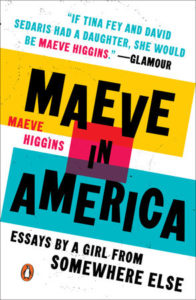

From Maeve in America: Essays by a Girl from Somewhere Else. Used with permission of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2018 by Maeve Higgins.

Maeve Higgins

Maeve Higgins is a contributing writer for The New York Times and the host of the hit podcast Maeve in America: Immigration IRL. She is a comedian who has performed all over the world, including in her native Ireland, Edinburgh, Melbourne, and Erbil. Now based in New York, she cohosts Neil deGrasse Tyson’s StarTalk, both the podcast and the TV show on National Geographic, and has also appeared on Comedy Central’s Inside Amy Schumer and on WNYC’s 2 Dope Queens.