February 12, 1954

I go to work thinking of death.

Hardly anyone in Seoul is happy during the morning commute, but I’m certain I’m one of the most miserable. Once again, I spent all last night grappling with horrible memories—memories of death. I fought them like a girl safeguarding her purity, but it was no use. I knew I was under an old cotton blanket, but I tussled with it as if it were a man or a coffin lid or heavy mounds of dirt, trusting that night would eventually end and death couldn’t be this awful. Finally, morning dawned. I looked worn out but tenacious, like a stocking hanging from my vanity. I used a liberal amount of Coty powder on my face to scare the darkness away. I put on my stockings, my dress, and my fingerless black lace gloves.

I walk down the early-morning streets as the vicious February wind whips my calves. I can’t possibly look pretty, caked as I am in makeup and shivering in the cold. “Enduring” would be a more apt description. Those who endure have a chance at beauty. I read that sentence once in some book. I’ve been testing that theory for the last few years, although my doubts are mounting.

As always, the passengers in the streetcar glance at me, unsettled. I am Alice J. Kim. My prematurely gray hair is dyed with beer and under a purple dotted scarf, I’m wearing a black wool coat and scuffed dark blue velvet shoes, and my lace gloves are as unapproachable as a widow’s black veil at a funeral. I look like a doll discarded by a bored foreign girl. I don’t belong in this city, where the cease-fire was declared not so long ago, but at the same time I might be the most appropriate person for this place.

I get off the streetcar and walk briskly. The road to the US military base isn’t one for a peaceful, leisurely stroll. White steam plumes up beyond the squelching muddy road. Women are doing laundry for the base in oil drums cut in half, swallowing hot steam as though they are working in hell. I avoid the eyes of the begging orphans wearing discarded military uniforms they’ve shortened themselves. The abject hunger in their bright eyes makes my gut clench. I shove past the shoeshine boys who tease me, thinking I’m a working girl who services foreigners, and hurry into the base.

Snow remaining on the rounded tin roof sparkles white under the clear morning sun. Warmth rolls over me as soon as I open the office door. This place is unimaginably peaceful, so different from the outside world. My black Underwood typewriter waits primly on my desk. I first put water in the coffeepot—the cup of coffee I have first thing when I get in is my breakfast. I can’t discount the possibility that I work at the military base solely for the free coffee.

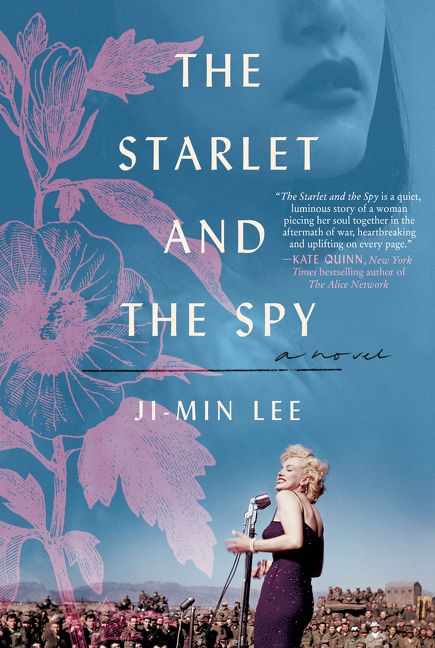

Marilyn Monroe. She moves like a mermaid taking her precarious first steps.I see new documents I’ll have to translate into English and into Korean. These are simple, not very important matters that can be handled by my English skills. First, I have to notify the Korean public security bureau that the US military will be participating in the Arbor Day events. Then I have to compose in English the plans for the baseball game between the two countries to celebrate the American Independence Day. My work basically consists of compiling useless information for the sake of binational amity.

“It’s freezing today, Alice,” Hammett says as he walks into the office, smiling his customary bright smile. “Seoul is as cold as Alaska.”

“Alaska? Have you been?” I respond, not looking up from the typewriter.

“Haven’t I told you? Before heading to Camp Drake in Tokyo, I spent some time at a small outpost in Alaska called Cold Bay. It’s frigid and barren. Just like Seoul.”

“I’d like to visit sometime.” I try to imagine a part of the world that is as discarded and ignored as Seoul, but I can’t. “I have big news!” Hammett changes the subject, slamming his hand on my desk excitedly.

I’ve never seen him like this. Startled, my finger presses down on the Y key, making a small bird footprint on the paper.

“You heard Marilyn Monroe married Joe DiMaggio, right? They’re on their honeymoon in Japan. Guess what—they’re coming here! It’s nearly finalized. General Christenberry asked her to perform for the troops and she immediately said yes. Can you believe it?”

Marilyn Monroe. She moves like a mermaid taking her precarious first steps, smiling stupidly, across the big screen rippling with light.

Hammett seems disappointed at my tepid response to this thrilling news. To him, it might be more exciting than the end of World War II.

“She’s married?” I say.

“Yes, to Joe DiMaggio. Two American icons in the same household! This is a big deal, Alice!”

I vaguely recall reading about Joe DiMaggio in a magazine. A famous baseball player. To me, Marilyn Monroe seems at odds with the institution of marriage.

“Even better,” Hammett continues, “they are looking for a female soldier to accompany her as her interpreter. I recommended you! You’re not a soldier, of course, but you have experience. You’ll spend four days with her as the Information Service representative. Isn’t that exciting? Maybe I should follow her around. Like Elliott Reid in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.”

Why is she coming to this godforsaken land? After all, American soldiers thank their lucky stars that they weren’t born Korean.

“We have a lot to do—we have to talk to the band, prepare a bouquet, and get her a few presents. What do you think we should give her? Folk crafts aren’t that special. Oh, what if you draw a portrait of her? Stars like that sort of thing.”

“A—a portrait?” I stammer, flushing all the way down my neck. “You can ask the PX portrait department . . .”

Hammett grins mischievously. “You’re the best artist I know.”

My mouth is dry. “I—I haven’t drawn anything in a long time.” I am as ashamed as an unmarried girl confessing she is pregnant. “And—and—I don’t know very much about her.”

“There’s nothing easier! People with faces that are easy to draw are the ones who become stars anyway. You don’t have to know anything about her. She is what you see.” He’s having a ball but then sobers when he catches my eye. That sharp gaze behind his good-natured laughter confirms the open secret that he probably is an intelligence officer. “Why don’t you draw anymore, anyway? You were a serious artist.” I’m flustered and trapped, and my fingers slip. Letters scatter across the white paper like broken branches. He might be the only one who remembers the person I was during more illustrious times. Among the living, that is.

“No, no. If I were a true artist I would have died in the war,” I murmur, and pretend to take a sip of coffee. My words leap into my coffee like a girl committing suicide. The resulting black ripples reverberate deep into my heart.

*

I leave work earlier than usual and take the streetcar to Namdaemun Gate.

A few months before the war broke out, a thoughtful someone had hung a Korean flag, an American flag, and a sign that exclaimed, welcome US navy! from the top of the centuries-old fortress gate. Perhaps thanks to its unflagging support of the US military, Namdaemun survived, though it suffered grievous wounds. I look at the landmark, the nation’s most famous disabled veteran, unable to offer any reassuring words. As if confused about how it survived, Namdaemun sits abjectly and seems to convey it would rather part ways with Seoul. I express my keen agreement as I pass it by.

The entrance to Chayu Market near Namdaemun teems with pedestrians, merchants, and American soldiers. All manner of dialects mingle with the pleasant Seoul accent and American slang. I fold my shoulders inward and try not to bump into anyone. The vitality and noise pumping out of the market are as intense and frightening as those on a battlefield. I am unable to keep up with the hunger for survival the people around me exude, so I make sure to stay out of their way. I duck around a fedora-wearing gentleman holding documents under his arm, a woman with a child on her back and an even larger bundle balanced on her head, and a man performing the acrobatic trick of napping on his feet, leaning against his A-frame. I head farther into the market.

At Mode Western Boutique, I find a group of women from the market who are part of an informal credit association. Mrs. Chang, who owns the boardinghouse I live in, also owns the boutique and oversees the group. The women are trading gossip over bolts of shiny Chinese silk and velour, but when I walk in they poke at each other, clamming up instantly. I’m used to their curious but scornful glances. I pretend not to notice and shoot Mrs. Chang a look in lieu of a greeting. Mrs. Chang swiftly collects the bills spread out on her purple brocade skirt and stands up.

“Ladies, you know Miss Kim, one of my boarders? She’s a typist at the base. Don’t you embarrass yourselves by saying anything in English.”

The women begin exchanging smutty jokes and laughing. With the women otherwise occupied, Mrs. Chang ushers me into the small room at the back of the shop. She turns on the light, revealing the English labels on dizzying stacks of cans, cigarettes, and makeup smuggled out of the base.

“Here you go.” I take out the dirty magazine I wrapped in pages torn out of a calendar. I asked an accommodating houseboy to get me a copy.

Only whores or spies take on an easy-to-pronounce foreign name.Mrs. Chang glances outside and gestures at me to lower my voice. She flips through the magazine rapidly and frowns upon seeing a white girl’s breasts, as large as big bowls. “Even these rags are better when they’re American-made,” she says, smiling awkwardly. “A good customer has been looking for this. I’ve been searching and searching, but the ones I come across are already fairly used, you know?”

I turn away from Mrs. Chang’s feeble excuse.

Mrs. Chang shows these magazines to her impotent husband. She lost all three of her children during the war. That is sad enough, but it’s unbearable that she’s trying for another child with her husband, who stinks of the herbal medicine he takes for his ailments. It’s obscene to picture this middle-aged woman, whose lower belly is now shrunken, opening Playboy for her husband who can barely sit up as she pines for her dead children. It’s too much to handle for even me.

“I’m sorry I had to ask an innocent girl like you to do an errand like this for me,” she says.

“That’s all right. Who says I’m innocent?”

Mrs. Chang studies me disapprovingly. “Don’t stay out too late. I’ll leave your dinner by your door.” Although her words are brusque, Mrs. Chang is the one person who worries about whether I’m eating enough.

Having fled the North during the war, Mrs. Chang is famously determined, as is evident in her success. She is known throughout the market for her miserly coldheartedness. That’s how pathetic I am—even someone like her is worried about me.

We met at the Koje Island refugee camp. In her eyes, I’m still hungry and traumatized. I was untrustworthy and strange back then, shunned even by the refugees. I babbled incoherently, in clear, sophisticated Seoul diction, sometimes even using English. I fainted any time I had to stand in line and shredded my blanket as I wept in the middle of the night. I was known as the crazy rich girl who had studied abroad. I cemented my reputation with a shocking incident, and after that Mrs. Chang took it upon herself to monitor me. When she looks at me I feel the urge to show her what people expect from me, though I doubt she wants me to. People seem to think I have lost my will to stand on my own two feet and that I will fall apart dramatically. I’m not being paranoid. I haven’t even exited the boutique and the women are already sizing up my bony rump and unleashing negative observations about how hard it would be for me to bear a child. They wouldn’t believe it even if I were to lie down in front of them right now and give birth. Somehow I have become a punch line.

A woman becomes lonely the moment she realizes her strength.Alice J. Kim. People do not like her.

Women approach me with suspicion and men walk away, having misunderstood me. Occasionally someone is intrigued, but they are a precious few: foreigners, or those whose kindness is detrimental to their own well-being. People don’t approve of me, beginning with my name. “Alice? Are you being snooty because you happen to know a little English?”

Very few know my real name or why I discarded Kim Ae-sun to become Alice. I’m the one person in the world who knows what my middle initial stands for.

Only whores or spies take on an easy-to-pronounce foreign name—I am either disappointing my parents or betraying my country. People think I am a prostitute who services high-level American military officers; at one point I was known as the UN whore, which is certainly more explicit than UN madam (I was just grateful to be linked to an entity that is working for world peace). Or else they say I’m insane. Now, to be a whore and insane at the same time—if I were a natural phenomenon, I would be that rare unlucky day that brings both lightning and hail.

People will occasionally summon their courage to ask me point-blank. Once, an American officer took out his wallet, saying, “I’d like to see for myself. Do an Oriental girl’s privates go horizontal or vertical?” I told him, “Every woman’s privates look the same as your mother’s.” The officer cleared his throat in embarrassment before fleeing. Anyway, in my experience, a life shrouded in suspicion isn’t always bad. No matter how awful, keeping secrets is more protective than revealing the truth. Secrets tend to draw out the other person’s fear. Without secrets, I would be completely destitute. Once, I heard Mrs. Chang attempt to defend me. “Listen. It wasn’t just one or two women who went insane during the war. We all saw mothers trying to breastfeed their dead babies and maimed little girls crawling around looking for their younger siblings. I remember an old woman in Hungnam who embraced her disabled son while they leaped off the wharf to their deaths.” She implied that I was just one of countless women who had gone crazy during the war and that I should be accepted as such.

But even Mrs. Chang, who considers herself my guardian, most certainly doesn’t like me. I’ve been brought into her care because the intended recipients of her maternal instinct have died. Maternal instinct—I’ve never had it, but I wonder if it’s similar to opium. You can try to stay away from it your entire life, but it would be incredibly hard to quit once you’ve tasted it. That is what maternal instinct is—grand and powerful and far-reaching. During the war the most heartbreaking scenes were of mothers standing next to their dead children. Maybe not. The most heartbreaking scenes during the war can’t be described in words.

In any case, perhaps confusing me for her daughter, Mrs. Chang meddles constantly in my affairs. It goes without saying that she has a litany of complaints. She looks at me with contempt. After all, I rinse my hair with beer, a tip I learned from an actual prostitute. That is certainly something to look down on, but I do have my reasons. My hair is completely gray. One autumn long ago, I grew old in the span of a single day. Afterward my hair never returned to its true color. My unsightly hair has the texture of rusted rope, but I’m satisfied with it for the time being. Mrs. Chang also despises my vulgar clothes, unbefitting, she says, of my status as an educated woman. But none of the things I’d learned academically helped me in the decisive moment of my life; my intelligence and talents, though not that deep or superior, were actually what entrapped me. Nor does Mrs. Chang think highly of my personality. She says I am haughty, which she thinks is why I don’t like people, but she’s not entirely correct. The truth is that I’m too broken. In any case, she cares for me in her heartless way and keeps me near. Even stranger is that I can’t seem to leave her, though I, too, look down on her. Our unusual connection yokes us together despite everything. She probably feels the sharp wind of Hungnam when she sees my bloodless cheeks. My pale forehead would remind her of the Koje Island refugee camp, where we were doused with anti-lice DDT powder as we sat on the dirt floor. Though we never meant to, we have somehow lived our lives together. We have a special bond, like all those who experienced war. We shared times of life and death. And she clearly remembers my triumphs and my defeats.

I triumphed by surviving but ended up surrendering; I tried to hang myself in the refugee camp, an act so shocking it cemented my reputation as a crazy woman. Mrs. Chang happened to walk by and pulled me down with her strong arms and brought me back to my senses with her vulgar cursing. Why did I want to plunge to my death after I’d survived bombings and massacres? I still don’t understand my reasons, but Mrs. Chang is certain in her own conjectures and stays by my side to watch over me. Hers is not the gaze of an older woman looking compassionately at a younger one. It’s the sad ache of a woman who is well versed in misfortune, feeling sympathy for a woman who is still uncomfortable with tragedy. If there’s a truth I’ve learned over the last few years, it’s that a woman’s strength comes not from age but from misfortune. I want to be exempted from this truth. I have earned the right to be strong, but now I do not want this strength. A woman becomes lonely the moment she realizes her strength. As loneliness is altogether too banal, for the moment I would like to politely decline.

__________________________________

From The Starlet and the Spy by Ji-min Lee. Used with the permission of the publisher, Harper Collins Publishers. Copyright © by Ji-min Lee. English language translation copyright 2019 by Chi-Young Kim. All rights reserved.