I had rented an apartment in London. An old part of London. This was where the Romans landed, rowing up the wide river, wooded on both banks. Much later, this eastern, marshy plain sat outside the walls of the city. There was a leper hospital here. You can hear it in the name: Spitalfields.

Now, still, if you follow them on foot, the medieval cart tracks of alleys and passages wind round towards the main road. Now, still, if you look, the past lies in layers of time, sedimentary, compressed, with pockets and tunnels where what has gone has not quite vanished, but holds its form. The buildings, yes, the topography, of course, and something else; an atmosphere, like a gas, escaping from those pockets, through those tunnels, reaching the surface.

The house was surrounded by newness. Empires of glass welcomed lawyers and bankers. The streets had been repurposed with coffee shops and sandwich booths. Exclusive chocolate, expensive candles. Wine bars and pubs. Till late at night there was a smooth flow of human traffic. I was never nervous about walking home. The streets were well- lit, and if people were drunk, they weren’t looking for trouble.

The house was a typical Georgian layout of five floors: basement and attic, a ground floor, used commercially, then living quarters above.

The rent was modest. A bad tenant had left in a hurry. The landlady wanted a sensible person who would stay for a year. I can pass as a sensible person.

She told me she intended to return to live in the house herself. That suited me. I had recently jumped out of a marriage, and I wasn’t ready to settle anywhere. A year was what I needed. I transferred three months’ rent, we shook hands, and she gave me the keys.

These were not grand houses when they were built in the 1780s. Still, the windows were large and square-paned, and the dining room was half-panelled. Wide polished oak floorboards, and a narrow up- and- up winding staircase, took me quickly and treacherously from top to bottom. People were smaller then, and the treads on the stairs were made for small feet. Never mind, the banisters were sound, and the lights worked well enough. I say well enough, because there was, even in daylight, a shadow on the stairs, as if the light had turned its back.

I unpacked my clothes. I like to sleep in a nightshirt. Heavy cotton, blue or green, with thin white stripes. These are supplied by a gentlemen’s outfitters. I hung one on a hook by the bed. It looked like a meat hook, but the landlady assured me that the attic had been used to store bananas.

The bed was large and comfortable. New mattress. The room was peaceful. I slept well that first night, and if I heard a door open on the floor below, it must have been because I hadn’t closed it properly.

In the morning, as I went downstairs in my nightshirt to make coffee, I stood a moment on the half- landing, looking into the spare bedroom. Nothing there but a small iron bedstead, a chest of drawers, and a vintage desk and chair. 1950s. The landlady didn’t like any of it, but she had bought the house with the furniture, and it was fine for tenants. It was fine for me because I had left my furniture behind.

I thought I might use the room as an office once I got set up. I had barely glanced at it with the landlady, because as she talked, and as we walked up and down the stairs, I knew I would take the house. I knew it when she first unlocked the small front door above the single step onto the street.

Now, though, I could see that the top cover of the bed had been turned back, leaving a bare spread of sheet, as though someone had only just got out of it. Hesitating, I wondered if the landlady had left it like that, to make the place feel lived- in, the way cleaning ladies always arrange books and cushions at an angle. Yes, it must be so. It must be so because there was no other explanation. Quickly, a little too quickly for someone who was pretending not to be nervous, I tucked the quilt back under the single pillow, and smoothed the bed. There was a faint smell in the room – I am sensitive to smells – and I wondered, is it gas? Or perhaps a dead mouse? They smell similar. Methane. Well, it would soon right itself with air and use. I tried to raise the sash window, only to find it had been nailed shut. I could deal with that later.

For now, I left the door open, and continued into the kitchen, where everything was as I had left it the night before. I boiled the kettle and ground the coffee. Outside, on the street, people were hurrying to work. Fresh coffee and a new day. A new start. I felt better than I had done in a while.

Coffee over, I went out to buy a hammer and a pair of pliers to unfix the window. At the hardware store, I bought a mousetrap too, and wandered back to the house. I stood across the road, looking at this sloping, self-contained building, admiring the symmetry of the windows, and the handsome stone parapet that ran outside my attic bedroom. It was a good house, sitting above the little shop, a house that had seen centuries go by, and here it was, still, travelling through time, and that felt like hope to me.

Then I saw, or thought I saw, did I see it? I see the figure of a man in the spare room. A thin man, hair brushed back, wearing a jacket. I screwed up my eyes to focus. There’s no one there.

But I am wrong. Am I wrong? There is a shadow, a shape, a man at the window. He seems to be holding something in both hands, looking down at whatever it is he’s holding. My heart was beating too fast. Was someone hiding in the house? Did someone else have a key? Had they watched me leave and let themselves in?

A voice startled me. ‘You lookin’ for somethin’?’

It was the woman from the shop below me. I introduced myself. Her name is Joyce. She sells cushions and blankets. I explained I believed I had seen someone at the window. She laughed. ‘There’s no one in there, my dear. My daughter cleaned it from top to bottom before you moved in. There’s no bogeyman hiding in the cupboard.’

‘Does anyone else have a key?’

‘Wouldn’t matter if they did, my dear. The landlady changed the locks when the tenant before you did a flit in the night. I made the locksmith a cup of tea.’ Joyce was looking up. The window was blank.

‘Tell you what though, these bastards are cunning, and I suppose you never know. Not these days. I’ll come in with you, dear, take a look around, all right?’

All right.

Joyce and I went into the house. She said, ‘I’ll wait here. Anyone comes flying down the stairs, and they’ll have to get past me. Won’t be pleasant. You go on upstairs. Settle your mind.’

Reluctantly, I did so, holding on to the hammer. The spare room was just as I had left it. My attic bedroom was just as I had left it.

Relieved, if a little sheepish, I returned to the kitchen.

‘It’s the old glass,’ said Joyce, holding her hand up to the window. ‘Not like modern glass, see? It distorts.’

She’s right about that. Not all, but some of the panes are thick and swirled.

What I saw, thought I saw, must have been a reflection of a reflection. The glass buildings across the street projecting images onto my window. I’ve spooked myself, that’s all.

‘Well, you know where I am, my dear,’ said Joyce. ‘At least till six o’clock, and then I’ll be in The Golden Heart. The pub on the corner.’

Joyce went back downstairs to run her business. God knows what she thinks of me. I went upstairs to unfix the window. The nails were crudely hammered in. Jagged, uneven. It felt like anger. Why nail shut a window? No one could break in at this level. And whoever had nailed it up had done more than was necessary. Much more. There flashed in my mind a mouth full of yellow teeth, clamped round a bristle of dirty iron nails. Thick fingers on the hammer shaft.

Pull yourself together!

Beyond the window, across the road, I could see the silent mime show of office workers at their desks. That’s all it was. All it ever is.

What did Albert Camus say? It’s not one thing or the other that leads to madness; it’s the space in between them.

I’m living in a space between lives – my past and my future. I’m living in a space between worlds. How could I not feel like a crazy woman?

At last, the remaining bent and rusty nail split under the pliers. With some difficulty I pushed up the sash window. Every inch a reluctance. Then, with a jolt, it freed, and the air rushed in. It wasn’t like opening a window. It was like releasing a vacuum.

Behind me the bedroom door slammed shut.

It’s the wind. Only the wind. There’s no one here.

*

The day passed, and the next and the next, and I began to relax into the house. To make a routine. To let myself be. I realised how tense I had become, how wary, and it was not the house that had made me tense and wary, it was my own sadness at my loss, my own restlessness. I had no need of a ghost. I was my own haunting. They say, don’t they, that poltergeist activity can often be traced to the kinetic energy of teenagers? That there is such a thing as mind over matter, and that we externalise our internal states, even to the point of objects that seem to have a life of their own.

I had never thought about it before. But now, the house and I seem complicit, going about our days. This house is more than a neutral space. It seems to welcome me.

Even so, I didn’t set up my office in the spare room, and I kept the door closed.

After a couple of weeks, I had a meal booked with friends. The evening was fun and easy, and when we had eaten, we walked around the streets, enjoying the nightlife, taking our time. As I waved them goodbye at the underground station, I sensed someone looking at me.

In the crowds heading for trains, there was no one obvious, but as I walked away something made me turn back, and there, by the free- newspaper kiosk, was a man whose face I couldn’t see, didn’t need to see. I recognised his tall, thin body – or rather the body I thought I had seen in the window. I stood still, trying to be sure, but then another wave of revellers came between us, and once they had cleared, the only human left at the kiosk was a drunk zipping up his flies.

At the house, I went through my usual evening routine. I put on the blue nightshirt and got into bed. I like city noises when I am high up above them. It sounds as though it’s the sea, far away, and I am safe, because it’s nothing to do with me; it’s the way you feel safe as a child, when the grown- ups’ noises downstairs become the soundtrack of sleep.

I dreamed of Clive.

Some time in the night, in the deep night, in the stretched- out hours before morning, I woke up. That is,

I was awakened by a clicking I didn’t recognise. I lay there listening, ears sharp as a bat’s. For a while, nothing, and then the metallic clicking. Five clicks, rhythmic, repeated. But what is it?

My brain searched its database. I know the sound but what is it? It’s a long time ago. My father.

It’s a cigarette lighter. Compact. Held in one hand.

The clicking is coming from the room below me. The spare room.

The staircase here is an open funnel. It leads from the kitchen, directly to the attic, and the attic is open. No door. The top of the stairs becomes the room itself.

I realised that the smell I had noticed in the spare room was this same smell; not methane but another kind of gas – lighter fluid. Butane.

I waited, still as a hunted animal. There were no human sounds from below. Then my nose twitched, as the cigarette smoke reached my bedroom.

There is no way round this. Someone has lit a cigarette, and someone is smoking it on the floor below.

I reached for my cell phone on the bedside table. 01:38am. OK. If I call a friend, I will be heard. If I call the police, they will be taking my details long after I’m officially dead. I decided to send a text to my friend Billy. He runs a restaurant. Maybe he’s awake.

But the rest I will have to deal with myself. What’s better? Boldness? Stealth? How much time has passed? No idea. I can’t bear the thought of lying here, then hearing him – I am sure it’s a him – coming up the stairs to this room where I shall be trapped. I have to act now.

I put on the bedside light, swung my legs to the floor, making as much noise as possible. This room is carpeted. I pulled on trousers, trainers, put a pair of nail scissors in my pocket, the only weapon I had to hand, and went downstairs.

On the landing, there was no sound. The door to my little sitting room was closed. I opened it and went in. The street light flickered yellow at the corner. There was no one around. It’s a weekday and nearly 2am now. Turning, I faced the door to the spare room. It’s closed. Do I have to open it? Yes. I do.

Come on!

I kicked it. The door flew open. The room was dark. I could see the foot of the bed. I have to go inside. My hand gropes for the light switch.

At that second, my front doorbell rings, shrill, insistent, intermittent, like an old- fashioned telephone.

My God, who is it? What’s going on?

I crossed the landing into the sitting room, and pushed open the window, looking down on the deserted street. It’s Billy.

*

Once inside, I pour us both a brandy. He’s cycled here. He was just going to bed when he got my message. He set off without thinking. He knows I’ve been having some problems since the break- up. He can see my frightened face.

I asked him to go into the spare room with me. We went together, stood on the landing. ‘Can you smell it? The smoke?’

Billy looked at me, shaking his head. ‘It’s a bit musty, I guess, but it’s not smoke. You had a fire?’

‘Cigarette smoke.’

Billy listened while I told him the story. He didn’t speak. When I had finished, he offered to stay the night, in the room. He was tired out anyway, and if he stayed, then I would sleep better.

I looked at him, curly-haired, kind. He had saved me.

‘That’s great,’ I said. ‘Yes. I’ll get you a toothbrush and a towel.’

‘You got a spare T- shirt to sleep in?’ he asked. ‘It’s chilly in here.’

‘I’ll get you one of Clive’s nightshirts,’ I said.

*

Billy went downstairs for a glass of water, while I collected the items he needed. I rummaged in my cupboard for the green nightshirt but couldn’t find it. Was it still in the wash?

Well, no use if it was, and I was wearing the blue one. My ex has the red one, the grey one, the white one with a cream stripe. I picked a baggy T- shirt from the pile.

‘Not back at work yet?’ asked Billy.

‘Still signed off. Another week, I think. I’m much better.’

Billy nodded. ‘Are you taking the amitriptyline?’

‘Yes. It’s working. I’m mostly fine. It’s smoothed the edges. It’s hard, you know, getting divorced.’

Billy gave me a hug. ‘Love is hard – whether you got it or you don’t.’

‘Thanks for coming over.’

‘Get some sleep.’

It was nearly three o’clock. Below me, I heard Billy creak around in the narrow bed, and then, quickly, his snores. I smiled to myself. No one could be living in that room in secret without me knowing. I can hear everything. The house is porous.

*

I slept deeply. It was past ten o’clock when I awoke. Billy had left. His note told me to call him anytime.

I looked around. I am a neat and tidy person, but the house was messy. What’s the matter with me? I need to do the laundry, start cleaning, get a bit of Buddhist mental orderliness about me.

Start with washing up. Glasses, toast plate from yesterday, mugs, coffee pot and little cup. I turned on the radio, flitting about with the dishcloth, feeling lighter and better. My phone pinged – Billy. I hit reply – Yes, I am fine, sorry I didn’t take you to breakfast, good you found the coffee.

I was so in flow with my cleaning that it was a half-hour later that I checked his return message:

No worries! Let’s have breakfast on Saturday. You know I don’t drink coffee! (green retch emoji)

I stared at the phone. That’s right. I know that’s right. Billy doesn’t drink coffee. But I washed up the coffee pot this morning.

Must have been from yesterday – like the toast plate.

Did I have toast yesterday?

Pull yourself together, girl.

*

By lunchtime, my house was perfect. Laundry done. The only thing still missing was the nightshirt. In the bed? Under the bed?

No. But this gave me an excuse to change both the beds in the house. In the spare room, with the window open, nothing was wrong. Nothing at all. It’s a lovely little room. There’s a simple fire- surround. A mantelpiece with a seascape propped on it. It’s a boring picture but not a bad one. I should hang it up. I’ve some picture hooks and my new hammer. Make the room my own. I will put my office in here today. That feels good.

I fetched the bits and pieces, stood on a chair, and lifted the picture, adjusting it until it hung straight. My old schoolteacher used to say, ‘Pictures are hung. Men are hanged.’ A gruesome but effective grammar lesson.

I turned it over. Brown paper backing, and twisted steel wire, the wire now rusted with the damp of history. And something else. Faded red- brown stains. Fingerprint stains. Bloodstains. As if someone had cut their fingers twisting the steel wire. I pulled at the paper where it had come away from the frame. There was another picture underneath the seascape. No, not a picture, a small photograph. Black and white with a border. Kodak.

I didn’t recognise the woman. But I recognised the man. The whippet of a man with his arm around her waist. He’s wearing a white shirt, open at the neck, its collar folded over the collar of his baggy blazer.

Had the photograph been hidden? Or covered up?

I looked down at the mantelshelf from where I had moved the picture. I saw the cigarette lighter.

Dry in the mouth, I picked it up. It was made of steel, small and square. I clicked the top. The flint lifted over the roller. Five clicks to produce a flame. Click click click click click. Butane.

I put it back on the mantelshelf, with the picture, and closed the door to the spare room.

*

In my coat, hurrying out, I saw Joyce from downstairs.

‘Settling in?’ she asked. ‘I saw your boyfriend this morning.’

‘He’s not my boyfriend. He stayed the night. That’s all.’

‘I don’t mind, dear,’ said Joyce.

‘I was frightened in the night.’

She looked at me oddly. ‘You being spooked again?’

‘I think I am.’

‘It’s your imagination,’ she said. ‘You look artistic.’

‘Has there ever been any trouble in this house?’

‘There’s ghost tours all round this area. Ghost. Horror. Jack the Ripper. Kray Twins. Werewolf.’

I was silent.

Joyce smiled. Nodded. ‘Cheer up,’ she said.

Joyce is right. I need to get myself together and get back to work and stop inventing problems to distract me from my own.

I am seeing my ex today. Clive. A few logistics to clear up.

*

We meet for coffee, and he is what he always was: handsome, detached, difficult, decent. When we split up, he offered to pay my rental for a year, because I was moving out of his flat, and my own flat is let. I accepted. He has a well-paid job in finance. I am not sorry we parted. I am broken-hearted. Both of those statements are true. Sometimes, you have to hold in managed conflict truths that cannot be reconciled.

There he is: neat, groomed, softly spoken. Considerate, and at the same time indifferent to what has happened. He’s over it, but he has standards, and he doesn’t like mess. He wants me to think well of him because he needs to think well of himself.

‘I miss you,’ I say. He smiles and stirs his coffee even though he doesn’t take sugar.

‘It’s just a feeling,’ I say. ‘There’s no need to be afraid of it.’

That’s how it was. Me, trying to get him to feel. Him, living in the penthouse of his body; his mind. Wonderful views. No connection to what went on lower down. Empty rooms. Boarded windows. Locked doors. Keep Out.

The things we did together were fun and interesting. Travel. Culture. Good restaurants. Nice people. For the long-term, though, there has to be more than ‘do’. You have to be. To be together. To be yourself. To be safe.

‘Back at work yet?’ he asks.

‘Not yet.’

Why does he feel strong? Why do I feel weak? He’s not strong. I’m not weak. The waitress glances at me as he pays the bill. She’s seen it all before.

When we part, he walks towards the station, pausing outside the shoe- shop window, then to notice a pretty face. I follow him, I don’t know why, until he begins to descend the steps to the station. He picks up a free newspaper. He doesn’t look back.

*

As I returned to my house, I felt exhausted. It’s mental, not physical. Why did I see him? I need to lie down.

I dumped my bag in the kitchen, washed my hands, and went up the stairs. The door to the spare room was open. The bed was neatly made. On the top of the covers, crumpled, hasty, and used, was the green nightshirt.

Like someone in a trance I went to pick it up. Rancid.

The nightshirt smelled of sweat, tobacco, grease, dirt. Tea stain down the front like a birthmark. Stinking, like it had been worn for weeks by a body that doesn’t wash. Moving in its own filth. Worse yet, watching it, waiting for it to squirm with life, I saw that the lower buttons had been ripped off – fiercely. And ripped off while the occupant was wearing it: the buttonholes were torn.

I backed onto the landing. I closed the spare- room door. My fingers were sticky. Downstairs again, in the kitchen, I ran the hot water till it burned me.

What was this? Who was this?

I did the deep-breathing thing that is supposed to keep us calm. Instead, I raised a clear picture in my mind of the last time I had made love with Clive. The last time we were together. But we weren’t together because he was doing it out of pity. Later, fixing himself a drink, he was wearing the nightshirt.

When he had gone to shower, I had stuffed it in my bag. I wanted his smell; his seasalt and wood-sage cologne. His whisky. His body.

I went in the cupboard and took the clean blue one as well. His things. But also, to steal his things. To take from him as he had taken from me.

I need to get rid of those nightshirts. Both of them. Today.

Rubbish bag. Meat tongs. I can barely look in the room as I reach forward to pick up the swinish shirt. It wriggles on the end of the meat tongs. Inside the plastic bag, it’s moving. Lice.

On the street I run to the first bin I can see and stoke it down inside. A woman glances at me like I’m crazy.

Yes, I have been crazy, but I’m less crazy now. Sanity like clean water is flowing through my mind.

*

I went to the flower stall near the house and bought a simple bunch of daffodils. Nothing special. Nothing fancy.

Back at the house I went straight to the spare room, stripped the bed, threw the bedding into the washing machine, and put the flowers in a jug on the chest of drawers.

In my own room, I took the blue nightshirt from under my pillow, sealed it in a Jiffy bag, ran out and posted it back to Clive. He can wash it himself.

These things done, I returned to the spare room, sat on the bed, and I said, ‘Whatever is in this room, listen to me. You and I are both lost souls. You are caught here, depressed, it seems to me, because you don’t care to clean yourself or to take care of yourself, and every animal manages that much. Me, I am going through the motions of a real life, but my life is still caught on the hook of a man who doesn’t love me.’

The room felt still, as if it were listening. As if someone was listening.

I got up, found the black and white Kodak snapshot, and propped it by the daffodils. The man was smiling so wide. The woman was looking away, her mouth set in boredom, or perhaps it was dislike.

‘She doesn’t love you,’ I said.

Then I went out and closed the door.

*

The following week, I started work in the office again. My colleagues were glad to see me. Soon I was going out with friends on Saturdays and I started seeing Billy more often.

I am still haunting myself. Still thinking of Clive, sudden and painful, but when it happens, I no longer hate myself. I let the thought come and go. No judgement.

In the house, things are different. There have been no further disturbances, except one.

I went into the spare room to get rid of the daffodils. Don’t want dead flowers.

The smell in the room had changed. The fuzzy smell of butane had been replaced with what was distinctly oranges. Sharp, citrus, clean, invigorating. Not perfume or candles. Fruit.

The photograph I had propped by the flowers had gone too. I searched behind the chest of drawers, and under the bed; had a draught blown it somewhere?

*

Only towards the end of my tenancy, nearly a year later, when I was handing over to the landlady, did I discover that the house had been lived in by an oranges importer in the 1950s, in the days when Spitalfields Market supplied all of London’s fruit and vegetables. Oranges from Seville were especially prized.

‘I didn’t want to worry you,’ she said. ‘He killed himself in the spare room.’

__________________________________

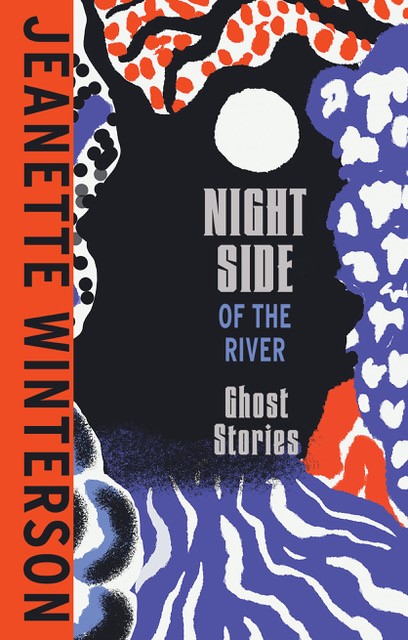

“The Spare Room” is excerpted from Night Side of the River by Jeanette Winterson. © 2023 by Jeanette Winterson. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.